This year marks the 75th anniversary of the United States victory over Germany and Japan in World War II, and the celebrations, the movies and the memorials will focus on the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific. But one of the most consequential battles of the war did not take place overseas. It was waged about 35 miles north of Chicago—and its outcome forever changed the U.S. Navy.

In early 1944, as the United States prepared for the invasion of France, 16 African American sailors, summoned from shore installations and training schools across the country, were brought to the main office at Great Lakes Naval Training Center and told they had been selected for Officer Candidate School.

It was a startling assignment.

A black man had graduated the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1877 and the Army had its first black general in 1940. But when World War II began, African Americans were not even allowed to enlist in the Navy’s general service. They were relegated to messmen: cooks and waiters whose chief function was to serve whites. Just two years later, thanks to pressure from civil rights leaders and the black press, the Navy told these 16 enlistees — the sons and grandsons of slaves — that they would attempt to integrate the officer corps and prove wrong the prevailing wisdom, which held that their race was incapable of discipline and unworthy of rank.

The story of the Navy’s first black officers remains little known, overshadowed by the heroism of the Tuskegee Airmen and Patton’s Panthers. But their success, both as candidates and as officers, forever changed what was possible for African American sailors and anticipated the coming civil rights movement.

These officer candidates were not career military men. Prior to the war, they were metalsmiths, teachers, lawyers, college students, men who had witnessed lynchings and been denied jobs because of their skin, men who were segregated and humiliated even after enlisting. But when the opportunity to break the Navy’s most rigid color barrier was presented, they swore they’d work harder than they ever had — for their own sake, for the countless souls who fought to make this moment possible and for the all the black men yet to come.

“We were the hopes and aspirations of the blacks in the Navy,” William Sylvester White recalled 30 years later. “We were the forerunners. What we did or did not do determined whether the program expanded or failed.”

There were roughly 100,000 black men in the Navy in January 1944. If any were ever to wear the gold stripes, to command a warship or graduate the Naval Academy, then this experiment would have to succeed. The candidates’ training was the culmination of an unprecedented four-year push by civil rights leaders who demanded to know why black parents should sacrifice their sons to free Europe for a Democratic ideal that didn’t exist in the United States.

“We want democracy in Alabama, Arkansas, in Mississippi and Michigan, in the District of Columbia, in the Senate of the United States,” the NAACP editorialized in 1940.

Even after Pearl Harbor and the formal declaration of war, many African Americans found that the calls to defend democracy rang hollow, while the German talk of a superior race sounded strikingly familiar. The black press, a formidable political force whose influence in the African American community was rivaled only by the church, launched the Double V campaign, telling millions of readers that a true victory for democracy would only be gained if it was won both overseas and at home.

Ordinary citizens wrote their congressmen, senators, the President and his cabinet to protest a policy that deemed their sons — who were eager to enlist in the Navy — fit only to wash dishes or scrub floors.

“It seems to me that that is a very cold and ugly situation,” J. E. Branham, a realtor from Cleveland, wrote Navy Secretary Frank Knox.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Their persistence led to 16 African American men being escorted to a Great Lakes barracks, which had 16 cots, 16 footlockers and one long table with 16 chairs. This was their home and their school. They were segregated from white officer candidates and separated from other black enlisted men. They were ordered to tell no one but their families what they were attempting. They were supposed to be in bed with the lights out at 10:30 p.m., but well past that hour, they sat together in the bathroom, flashlights in hand, studying seamanship, navigation, gunnery, naval regulation and naval law. They draped sheets over the windows so no one outside would notice the light. They were intent on proving that their “selection was justified,” Sam Barnes said, during the group’s first reunion in 1977, “and that we weren’t a party to tokenism.”

The men, who ranged in age from 23 to 36 years old, mastered in only a few weeks what many white candidates studied for years.

As their training drew to a close in March 1944, the group was posting grades like no other officer class in history. Their marks were so good, in fact, that some in Washington did not believe they could be real. The men were forced to take some exams a second time. They scored even higher, a collective 3.89 out of 4.0, the highest average of any class in Navy history.

Read More: These Photos of a Segregated U.S. Navy Unit Were Lost for Decades. They Still Have a Story to Tell

Despite their success in the classroom, Navy officials decided that only 12 would be commissioned and a 13th would be made a warrant officer. No official explanation was ever given as to why three men were dropped from the program—but the decision meant that the first group of black officers, a group that passed with flying colors, would have the same completion rate as an average white class.

Their initial success did not mean these groundbreaking black ensigns would be spared future slights. They were refused housing, prohibited from officers’ clubs and denied a chance to prove their mettle in combat. They were given make-work assignments: running drills, giving lectures on venereal disease and patrolling the waters off the California coast in a converted yacht. White enlisted men crossed the street to avoid saluting. The Navy kept their commissioning a quiet affair. There were no graduation exercises, no ceremonies, no celebrations. The Navy did nothing to promote their achievements even as they earned plaudits from their superiors and distinguished themselves in their post-war careers. For three decades, they were known only as “those Negro officers” of, later, as “those black officers.”

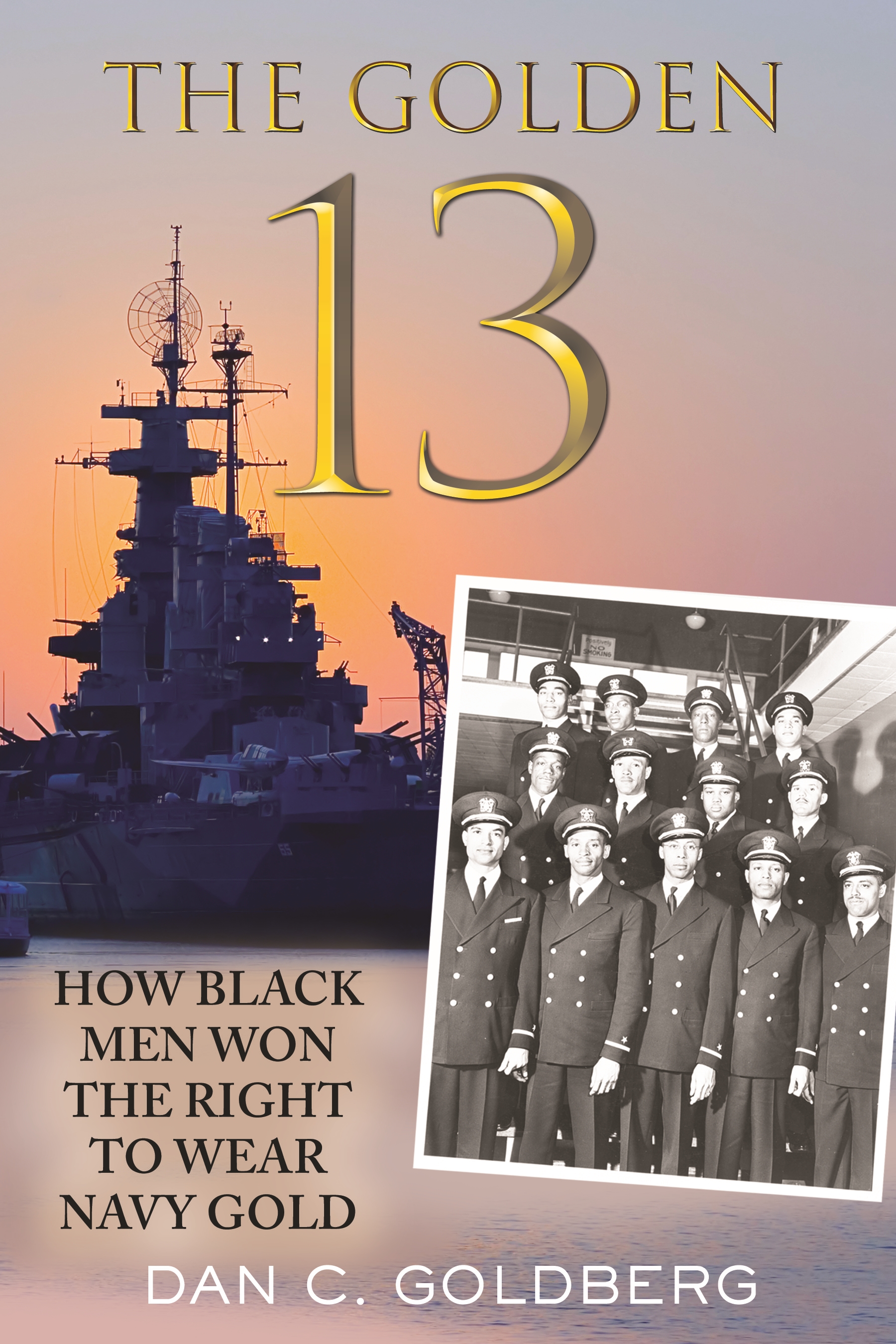

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the Navy feted these men as symbols of pride and progress, a recruiting tool to inspire a new generation. Prior to their first reunion in 1977, Captain Edward Sechrest, a Vietnam veteran who was assigned to the Navy Recruiting Command, coined the term “Golden Thirteen,” a bit of ingenious PR that gave the group a catchy nickname the Navy could use to tout their achievements.

Their annual reunions garnered some press but, as the men began to pass, their story faded from memory. Few today are aware of the Golden Thirteen or their contribution to the Navy and the nation. Still, the lessons they imparted are more resonant than ever before. At a time of national trial, the Golden Thirteen remind us that our capacity for success isn’t limited by politics or preconceived notions, that heroes aren’t only found in cockpits and tanks and that, often, the most important victories for Democracy are those won off the battle field.

Dan C. Goldberg, a journalist for Politico, is the author of The Golden Thirteen: How Black Men Won the Right to Wear Navy Gold, available now from Beacon Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com