Patients lie motionless in a hospital ICU ward, as doctors hurry around their beds. The patients’ faces are concealed by ventilators; the doctors’ by masks. The death rate is rising so quickly that doctors can no longer keep count. “The beds don’t even have time to cool before they are taken up by other patients,” says ICU nurse Cristina Pilati. Yet over the sound of stretchers rolling and monitors beeping, Pilati starts singing the lyrics of ‘Angel’ as she cares for a teenage boy in the ICU. ‘Spend all your time waiting, for that second chance,’ she sings. ‘For a break that would make it okay.’

This scene is one of many intimate moments in Inside Italy’s COVID War, a PBS’ FRONTLINE documentary premiering Tuesday that takes us inside a hard-hit hospital in Cremona, a city in northern Italy. Directed by Emmy and BAFTA award-winning filmmaker Sasha Joelle Achilli, who was born and raised in Milan, the film offers one of the first in-depth looks at a hospital battling coronavirus when the crisis hit. Achilli spent several months in West Africa documenting the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak, but filming the coronavirus pandemic in her native country, where her family still lives, presented new difficulties. “Emotionally, it was really challenging. It feels so much more personal,” she says. “But I feel really privileged that I was able to do that and get more of an understanding of this virus. When you understand something, you are less afraid of it.”

Achilli’s film follows emergency room doctor Francesca Mangiatordi as she navigates COVID-19, caring for her staff, her patients, and her family. Achilli, who now lives in London but traveled to Italy for filming, began shooting in Cremona on March 18, just one day before Italy’s death toll surpassed that of China, becoming the hardest hit country by COVID-19 at the time. More than 32,000 people have died from COVID-19 since the start of the country’s outbreak.

Keep up to date with our daily coronavirus newsletter by clicking here.

Italy’s health care system, the first to be hit hard in Europe, was quickly overwhelmed by the surge in cases. In the opening scenes of the documentary, doctors debate whether to give their remaining ventilator to a young or old person. Later in the film, doctors themselves fall ill, remaining quarantined in their homes as case numbers continue to rise throughout the country. The documentary also sheds light on the sacrifices frontline workers are making and the risks they are taking: Mangiatordi’s husband was at higher risk of catching the virus but she stayed working on the front line.

Perhaps what is most powerful yet unsettling about the documentary is that it disrupts one of the prominent narratives surrounding COVID-19: that the young and healthy won’t be severely affected. While young people are less likely to die of COVID-19, they are still susceptible to severe infection of the virus. The documentary follows an 18-year-old boy and a 30-year-old mother of three girls as they fight for their lives. “The next one that tells me it only affects the elderly, I’ll spit in their eye,” Mangiatordi says after a 42 year-old man died of COVID-19.

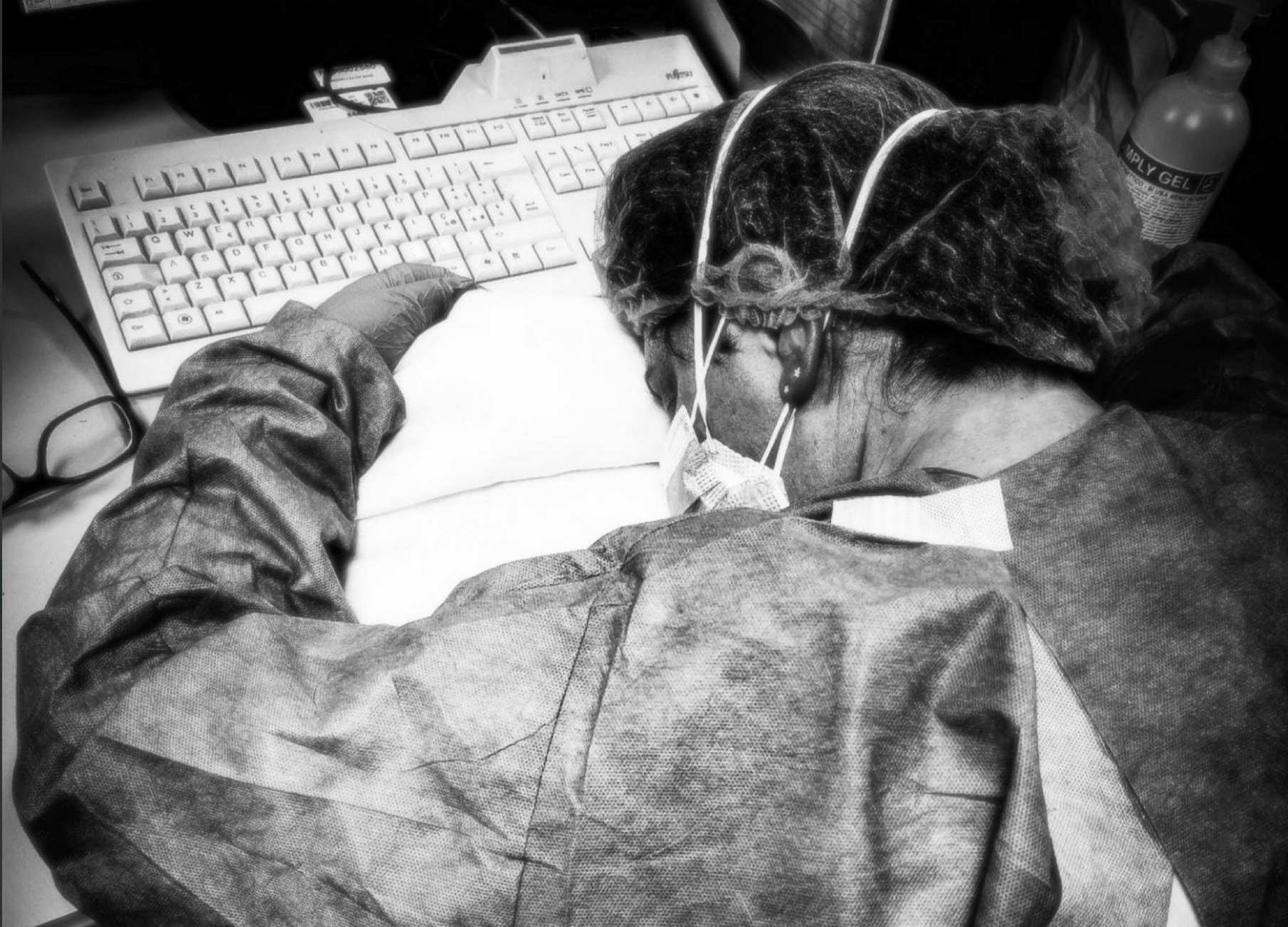

Achilli was inspired to make the documentary after coming across a photograph Mangiatordi took of an exhausted nurse, Elena Pagliarini, collapsed on her keyboard in early March. Within hours of seeing the photograph, the two women spoke on the phone. Days later, Achilli was filming at the hospital.

Achilli spoke with TIME about the making of the film. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your documentary is the most in-depth and intimate picture of a hospital battling COVID-19 we have so far. What do you hope people take away from it?

My goal has changed from when I first went to Italy. When I first went out, the borders in Europe were closing but the crisis hadn’t erupted yet. Back then, the message was “Italy is 3 weeks ahead of you.” But now we’re all in it. What I want people to get out of this documentary is an understanding of the virus. I want to squash all the conspiracy theories and for people to understand the emotional and psychological impact it has had on health care workers and those severely affected. I want people to realize that while there is no need to panic, there is a severity to this and we need to take the measures seriously. Italy is now coming out of it, hopefully. The cases have gone down massively. And it’s because of the lockdown and the measures that were taken that this is possible. That’s what I hope people get out of it. Especially American audiences, given the protests that are taking place. This is very real.

Because Italy was the first Western country to face a COVID-19 outbreak, many other nations in the West have looked at Italy to predict what the futures of their countries might look like. As someone who watched the outbreak unfold, what do you think the world can learn from Italy’s experience?

The world needed to look at Italy at the beginning. Now, the world is currently living it. Rather than critiquing the Italian draconian measures or the Italian culture of siesta, they should have taken them seriously and not thrown around the idea of herd immunity. If there is a country forcing people to stay home in this way, it means it’s serious. But until you see that every family has been affected by the virus or lost someone to it, until your morgues are completely full and coffins cannot be buried in time—until you see that, people’s behavior will not change.

These kinds of outbreaks are going to keep happening. We need to stop thinking of places as being far away. We are all so connected and way more connected than we like to believe. So when this started to happen in Italy, Europe should have started locking down before it got out of control. The U.S. should have taken it seriously. No one is immune to it.

What are the underreported stories of this crisis?

There was a point where 13% of cases in March in Italy were healthcare workers. Of course healthcare workers did have more access to tests so more of them were getting tested. But the numbers were still high.

I remember having this debate with Francesca and her husband: why did so many of the staff get sick? Part of it is a lack of disinfectant. The ER was never disinfected until three or four weeks into the outbreak. There was no methodology put in place. The hospital isn’t a structure that facilitates infectious disease triage. It’s hard to criticize an entity or a body or blame someone for all these cases in healthcare workers but we need to have structures that can handle highly infectious diseases.

As an Italian journalist who has reported on crises in Africa and the Middle East, what was it like reporting on the front lines of your own country?

Emotionally, it was really challenging. A lot of the stories I’ve done are really, really sad situations that do affect me emotionally. But there is something different about it when you’re covering it in your own country. It feels so much more personal. You know the culture, the language, the shared way of communicating without needing to speak. It just felt so much more personal and at the beginning, so emotionally exhausting in a way that I had not experienced in my career despite working on emotionally trying stories.

I think for me, the worst part was when I landed in Rome and I hadn’t been home since Christmas. I flew in and it was completely empty. It felt like something out of an apocalypse film, where cities are abandoned and people have left. I remember getting to the hotel. I called my boyfriend and just burst into tears because the lockdown hadn’t happened in London yet. Even though I had heard the stories through my family, seeing it and seeing your country—especially Italy which is so lively, where people hug and kiss all the time—to see it so completely empty and with the human interaction completely gone. It just wasn’t Italy. It wasn’t my country. It sounds absurd but that was a huge emotional trigger, almost more than going into a COVID hospital. Because there, I had prepared myself for what I would see. But I hadn’t prepared myself for Rome.

What was the highlight of the filming experience and what was the most challenging?

The highlight was the life I had with Francesca [Mangiatordi, the ER doctor in the documentary]. She opened her doors to me, completely and entirely. I was living her work life and then going home with her family. It was meeting her and her family and building that relationship as well as with the other nurses. I spoke with Cristina [one of the ICU nurses] the other day and she said “you were part of the family, you lived it with us. You are one of us.” Another highlight was being able to be part of such a big and important story in Italy and having that unique experience of living it on the frontlines with the healthcare workers. I feel really privileged that I was able to do that and get more of an understanding of this virus. When you understand something, you are less afraid of it.

The hardest thing as a journalist reporting on your country is that you become really protective of certain parts of the culture, of the way that people are and of the story you are trying to tell. You are an insider. It’s hard to take a step back and look at it in the same way that you look at other places. I’ve realized it’s a very different kind of storytelling when you know the language and you aren’t an outsider. It was really easy for me to get the level of intimacy that I got. I don’t think that would have been possible in other parts of the world. There’s a beauty about just looking around you and trying to tell the stories that are equally as important—the stories that are next door rather than elsewhere. It was really beautiful and it kind of brought me closer to Italy.

Both you and Francesca Mangiatordi are women working on the frontlines of this pandemic in what can often be quite male-dominated environments. In your experience, how does gender shape what it means to be a frontline worker?

Personally, I’ve often benefited from being a woman. We often have an ability to build better access and relationships with people, especially when it comes to women and children. Women are more likely to open up to women.

I didn’t set out to find a female doctor. I found her through a photo she had taken. And then she sent me her video diaries and I realized that she was incredible. Going to Italy, which can be really misogynistic, I thought I would just find a bunch of old, grumpy Italian men. But instead, I found this hospital filled with feisty young women—and men as well. It was women doing the hard work. There were groups of women transferring bodies on the frontlines of this battle.

I don’t mean to sound cheesy but this group of women on the frontlines—they are carers, they are multitaskers, they can deal with dramatic situations but also be very empathetic and present. That’s what made this group of women so incredible in fighting COVID.

I remember one night at the end of my time there, it was about 3 a.m. and the doctors had pizzas delivered. These doctors and nurses all sat down and started recounting what had happened in the past two months. It was like group therapy. That’s the bond they’ve been able to create with each other. Now, they are helping each other process by reflecting and analyzing it. They are this incredible unit. I think in a way, women often have that ability to talk to each other. We can talk about emotions. And that’s what made these women so strong.

You reported on the Ebola outbreak in West Africa back in 2015, producing the documentary Outbreak that explores the mismanagement of the crisis by both state and international authorities. Do you see similarities between the Ebola epidemic and the current COVID-19 pandemic? And what feels different about this outbreak?

What feels similar is that when it started in China, people thought it was far away. They probably remembered SARS which never really went beyond Asia. Even in talking to doctors like Francesca, they say that when they heard about COVID-19 on the news, they never thought it was going to come to Italy. And that’s exactly what happened in West Africa. There was an outbreak and when it was reported on, people said it was never going to get to the West. It was only when an American doctor got ill that people started paying attention.

The differences are mostly related to how unpredictable this virus is compared to Ebola. Even though Ebola is scarier, I felt like I had more control over not getting it. But with coronavirus, you just don’t know how it’s going to affect you. This is what makes COVID-19 more terrifying and uncontrollable. It’s also not like Ebola where people were hemorrhaging from their eyes. Or in West Africa where you would see people dying out on the street. That’s visually not what we see from COVID-19. That’s made it easy for people to dismiss.

At the beginning, it was the elderly that were highly affected by it. It’s cynical to say but seeing an elderly person unwell is a more acceptable image to many people than a young person. All these factors didn’t help us take the whole thing seriously. I remember a friend of mine in Milan sent me a message saying, “Sasha, I’m not seeing these really dramatic images coming out of hospitals.” People in Italy were questioning the severity of it because they weren’t seeing the drama.

Outbreak warns that the world is not safe from future epidemics. What did it feel like to watch an even bigger outbreak unfold five years after extensively reporting on Ebola?

I think when it started out in China, I was like everyone else. I thought it wouldn’t come here. I was supposed to go on a six months sabbatical traveling with my boyfriend in April. And when COVID-19 reached Italy, naively—even though I was emotionally really affected by what was going on—the borders of the world hadn’t closed yet. Naively, we just thought, we won’t go through Italy and Iran. If I’m being brutally honest here, even having reported on an outbreak in West Africa, it didn’t prepare me for this.

Inside Italy’s COVID War premieres on FRONTLINE (PBS) & begins streaming on YouTube on Tuesday, May 19 at 10 p.m. EST and will be available on pbs.org/frontline and the PBS Video App at 7 p.m. EST.

Please send any tips, leads, and stories to virus@time.com

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com