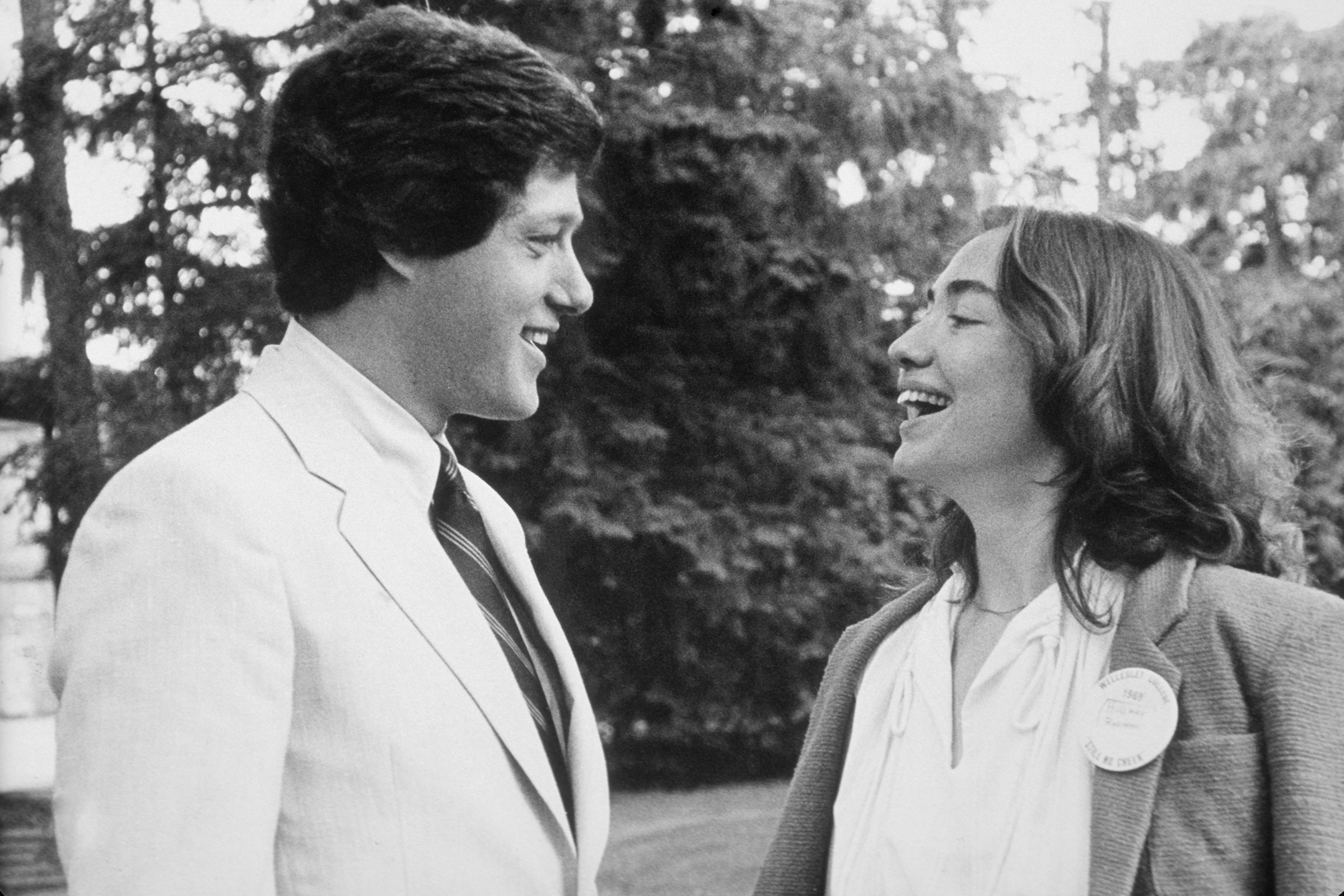

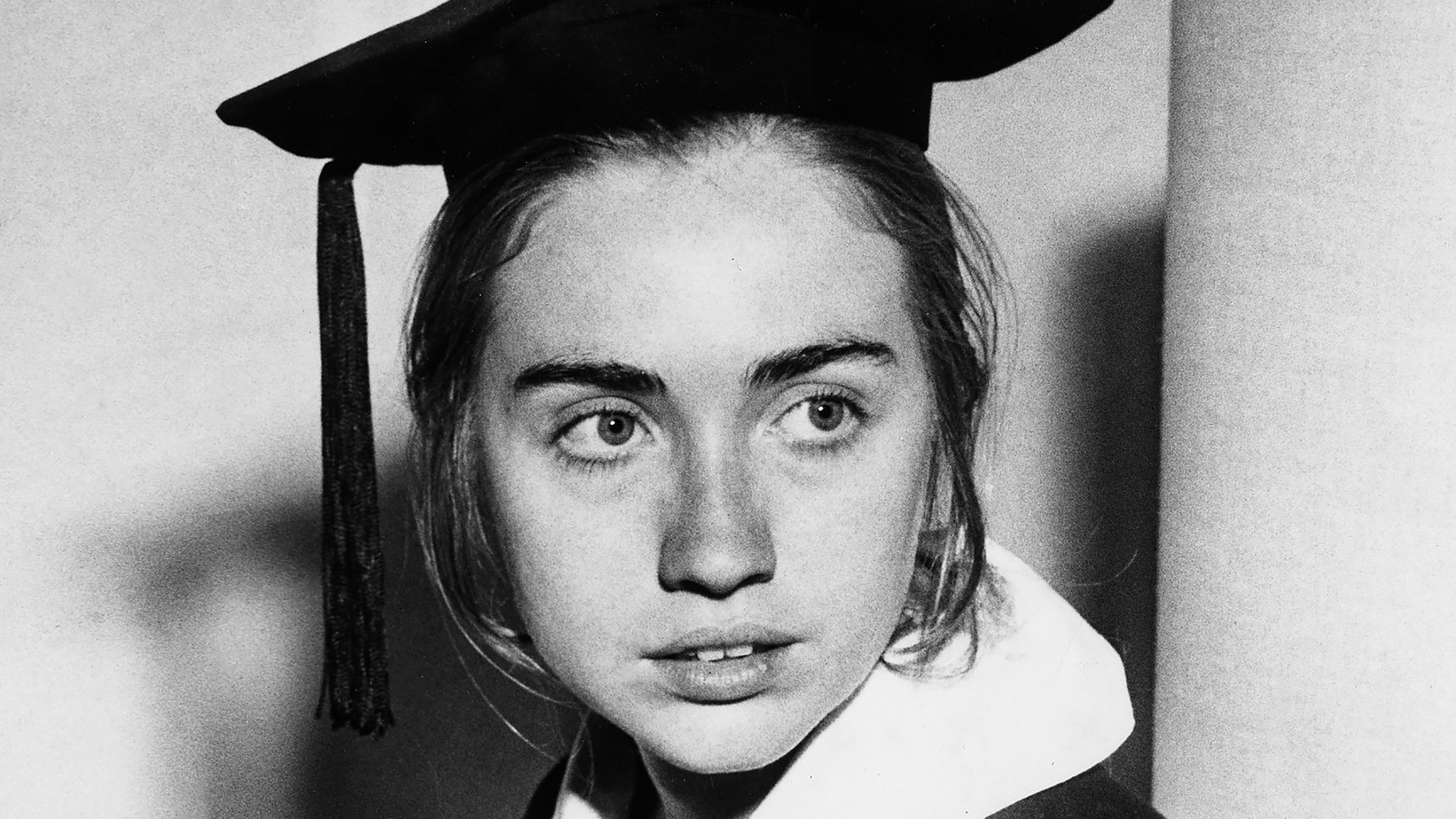

Hillary Rodham’s private and public lives became entwined the day she met Bill Clinton. From then on, her political aspirations would forever be tied to her charismatic partner — when it came to both his triumphs and his missteps. But even before she met Bill, Hillary had already learned to be stoic. In the recent Hulu documentary Hillary, she reflected on her time in 1970s law-school classrooms dominated by men: “You got points for not being emotional. When you train yourself like that and then you fast-forward into an age where everybody wants to see what your emotions are … it’s really a different environment.” So when scandal broke during Bill’s first presidential campaign, she compartmentalized her private life.

For years, pundits have called Hillary a cipher. At least some of this criticism is steeped in sexism — the dreaded “relatability” trap that women must be as warm and friendly as they are accomplished. Clinton has opened up professionally: she’s a policy wonk, a pragmatist and—unlike some politicians who rely mostly on charm — she thinks before she speaks. Supporters have interpreted those moments when the wheels spin in her head as thoughtfulness. Critics have called it calculation.

For all the speculation, Hillary Clinton is still widely perceived to be unknowable. She’s one of the most documented people on the planet, yet we’re resorting to fiction to try to understand her. In the highly anticipated Rodham, arriving May 19, best-selling author Curtis Sittenfeld doesn’t novelize Clinton’s life as it is but instead fantasizes about what could have been: What if Hillary hadn’t married Bill? No spoilers, but Sittenfeld’s answer is likely to alternately elate and enrage readers of all political affiliations. She spins a wild political tale that involves a certain lascivious New York City billionaire, a bizarre leg-shaving scandal and Silicon Valley orgies.

The author, who broke out with her 2005 debut Prep, has tackled a similar project before: in 2008, she published American Wife, in which a First Lady named Alice Blackwell — reminiscent of Laura Bush — attempts to explain why she, a book-smart woman who was raised a Democrat, stands silently by her militant President husband as the Iraq War spins out of control. Then on the eve of the 2016 election, Sittenfeld released a short story, “The Nominee,” told from the perspective of Hillary Clinton as she’s interviewed by a combative journalist.

But Rodham, her seventh book, gleefully abandons biographical analysis for thought experimentation. Unlike American Wife, which delved into traumas the real Bush experienced early in her life to explain her psychology, Rodham introduces a Hillary almost fully formed, at law school. Sittenfeld does not detail the childhood moments that might have shaped her politics, her religiosity or her ego. The reader must divine the origins of her ambition from her pillow talk with Bill.

Certain early passages read like cringe-inducing fan fiction: it would be one thing to encounter veiled approximations of Bill and Hillary getting hot and heavy in law school. It is quite another to read sex scenes that invoke the real names of one of America’s most prominent couples. Sittenfeld even goes so far as to imply that Bill is a sex addict, crumpled under the weight of an unstoppable affliction. (No doubt the publisher has a great legal team.)

While these carnal episodes will certainly serve to scandalize book clubs, they also are meant to solve this mystery: Why would a woman with such promise stay with a man torpedoing toward scandal?

Sittenfeld blends reported facts with imagined details. Fictional Hillary, she asserts in Rodham, was often spurned by romantic interests for being too intellectual or too assertive, and she felt flattered by charismatic Bill’s attentions. That’s a theory likely born from comments real-life Hillary has made over the years about her husband being “more attractive” than she is. As journalist Amy Chozick observed in her book Chasing Hillary, Clinton’s assessment of how her looks compare to those of her husband “isn’t really true.” But, Chozick added, it “always told me a lot about Hillary that she thought it was.”

Yet flirtation and flattery do not a power couple make. In Rodham, as in real life, these two share an intense intellectual connection. But it’s that very intellect that Sittenfeld argues would eventually drive Hillary away from Bill. In the book, the red flags Hillary identifies are far from subtle: early on, when the couple meets at a diner for a date, she marvels at Bill’s ability to both seduce her and gobble down french fries at the same time. “Bill, apparently, could be hungry for multiple things at once,” she notes. Her instinct that Bill’s appetites will get them both into trouble quickly comes to fruition. Their breakup feels inevitable — although, of course, the real Hillary stayed.

In a year when our attentions might more naturally be drawn to Joe Biden and Donald Trump, Sittenfeld isn’t alone in her continuing fascination with the Clintons. The aforementioned four-episode documentary Hillary, which premiered to much fanfare at Sundance in January, hit Hulu in March. Then the April season premiere of the CBS All Access legal procedural The Good Fight imagined an alternate universe in which Hillary Clinton won the presidency in 2016. And the next installment of Ryan Murphy’s popular miniseries American Crime Story, currently in preproduction, will focus on the Clinton impeachment.

Each of these projects, like Sittenfeld’s novel, obsesses over the consequences of Bill and Hillary’s relationship. In the Hulu doc, filmmaker Nanette Burstein asks both Clintons to recount Bill’s confession to his wife during the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Bill tears up, but it’s Hillary’s clipped response that disarms the viewer: “You have to go tell your daughter.” The line suggests a woman exhausted by her circumstances and unwilling, or unable, to express her outrage.

In The Good Fight’s alternate reality, the #MeToo movement never takes hold. Trump is never elected President, so there is no Women’s March. But the show also suggests that President Hillary Clinton, who defended her husband against accusations of assault, would prove an imperfect beacon for survivors. (She awards major donor Harvey Weinstein the Presidential Medal of Freedom.) And the writers for American Crime Story: Impeachment have said that the show, which will be produced by Lewinsky and told from her perspective, will not feature Hillary Clinton as a significant character because the First Lady declined to participate in the feminist debate over the scandal at the time. Three very different television series, but in each Hillary finds herself hamstrung by her husband’s misdeeds.

Considering Hillary is Hillary and Bill is Bill, I don’t think it’s giving too much away to say that after breaking up early in Rodham, the characters do not retreat into quiet lives of academia. As they both run for office, Sittenfeld theorizes that when it came to their political ambitions, Bill always needed Hillary more than Hillary needed Bill.

Sittenfeld, an admitted Hillary Clinton fan, reflects on real-life Hillary’s outsize role in Bill’s capturing the presidency through compelling vignettes. In her reimagining of the infamous 1992 60 Minutes interview — the one in which a confident- Hillary defended her husband amid allegations of infidelity, ultimately saving his candidacy — a different wife, meek and teary-eyed, sits beside Clinton and dooms his campaign. Meanwhile, in this fictional world, Hillary still faces sexism and defamatory rumors, including a murder for hire. But without Bill’s baggage, she’s able to handle controversy more deftly and answer questions more openly without worrying she may appear hypocritical.

And yet even as Sittenfeld grants Hillary the ability to finally do and say whatever she pleases, Rodham doesn’t always satisfy. For one, Sittenfeld never pinpoints a clear motivation for her hero’s desire to enter politics. Real-life Hillary notoriously switched her campaign slogans with abandon, which some took as proof that she could not articulate her reasons for running. Where supporters saw a woman responding to the call to service, critics accused her of being power hungry. Sittenfeld, despite the freedom of her format, lands on neither theory — nor does she offer a convincing alternative.

If her aim was to offer new insight into Hillary’s mind, she doesn’t succeed. But who cares? Even if the character isn’t compelling, her mission to break the glass ceiling is. For a certain reader, the chance to dwell in an alternate reality will be enough. For others, there’s always the orgies.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com