Everything hit Nick Martin when he picked up the phone.

Martin, 26, had expected to start a family medicine residency at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center this summer, after graduating from the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS). But with a surge of COVID-19 cases expected to hit the state in the coming weeks, the school allowed Martin and his classmates to graduate on March 31, so they could begin working as first-year residents in the UMass hospital system.

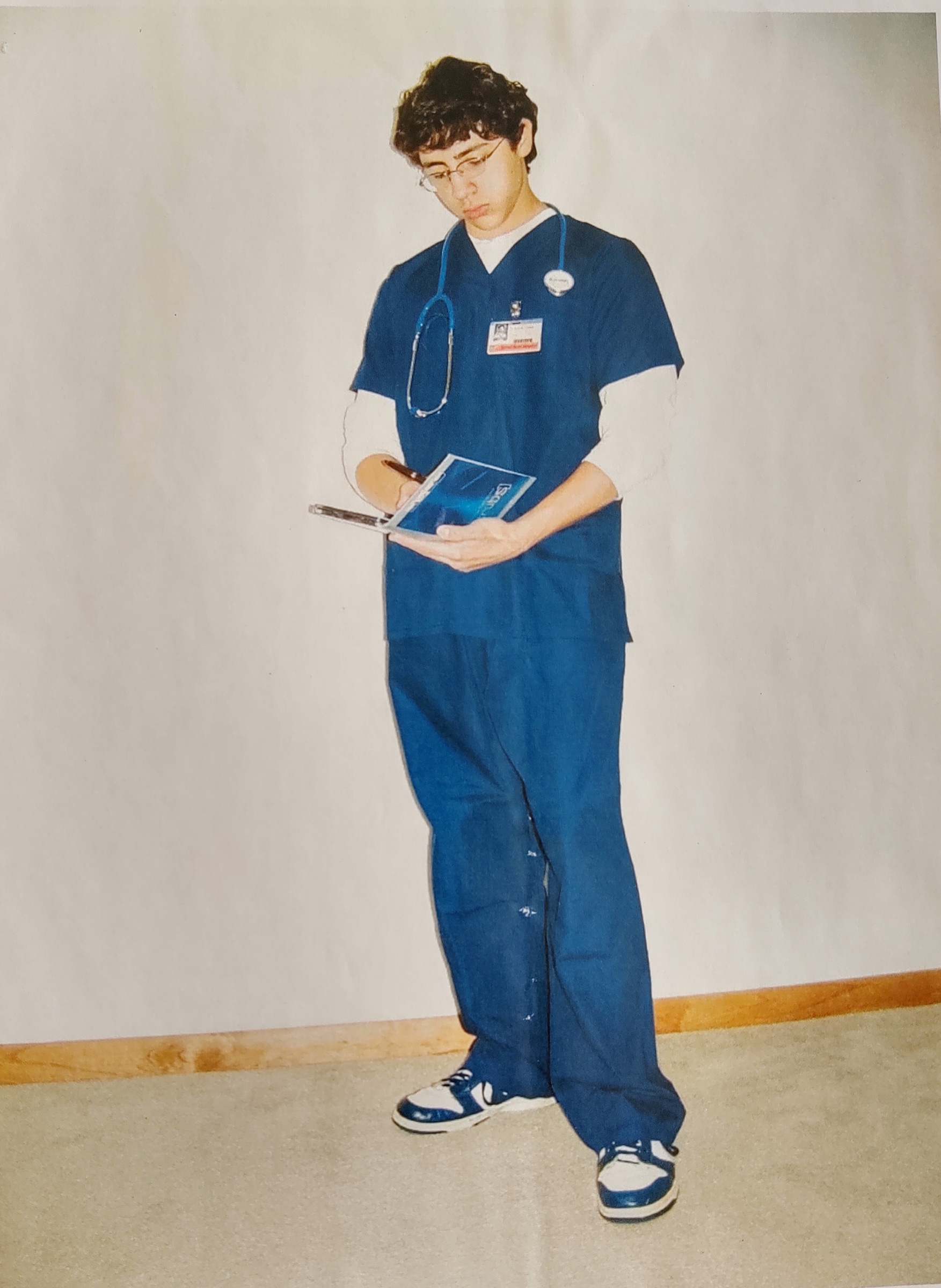

That’s how Martin found himself on April 8 in a white coat, calling into a coronavirus patient’s room and trying on a new name for the first time. “I was like, ‘I’m—oh, yeah, I’m Doctor Martin,’” he says. “It just gives you that next level of responsibility.”

Medical students across the country are in Martin’s shoes right now, collecting their degrees early to join the COVID-19 relief effort and ease burdens on overworked and understaffed hospital care teams. American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) records show at least 13 U.S. medical schools have allowed students to graduate early and join the COVID-19 response.

For years, experts have projected a looming physician shortage in the U.S., with much of the current workforce nearing retirement. By 2032, the AAMC estimates, the U.S. may be short up to 122,000 doctors.

COVID-19 has accelerated that timeline, as hospitals struggle to keep up with inflated patient numbers at the same time many health care workers are getting sick and being forced to stay home. New York state—the epicenter of the U.S. outbreak—needed about 1,200 more doctors to keep up with patient demand even before the pandemic hit, according to a WABC news estimate. With the situation suddenly even more dire, states including New York, California, Massachusetts and Illinois are turning to the country’s oldest and youngest doctors to help, asking both recently retired health care workers and graduating medical students to join the front-line response.

While a flurry of medical schools announced their plans in March, many newly minted doctors are not actually working yet. Schools have faced a thicket of logistical challenges, including getting plans approved by state-education and medical-licensing boards, and working with regulatory bodies to secure temporary licenses for doctors who weren’t planning to be in hospitals until July. Many have also had to sort out whether students would volunteer in hospitals associated with their medical schools, or join their planned residency programs early. And many new doctors have been left on their own to sort out the logistics of starting work, finding a place to live and making sure their planned residency programs are on board with the whole plan.

As a result, many students who have graduated and volunteered to serve are still stuck in limbo, their sense of duty tinged with fear.

Randy Casals, 28, was finishing up his last semester of medical school at Columbia University’s Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons this spring when the COVID-19 outbreak exploded. He and his classmates saw that New York University had announced it would let students graduate early to join the fight, so he was ready when the email came from his school telling him he could choose to do the same. “Starting our career in the middle of a global pandemic isn’t exactly what we signed up for, but helping people navigate really scary times is what we signed up for,” he says.

Columbia will let students graduate April 15 and temporarily start working at New York-Presbyterian Hospital soon after that. Casals, who is set to begin a urology residency at Wake Forest University School of Medicine this summer, still doesn’t know exactly what his work will look like in this interim period. Columbia has told the students they will be mostly providing relief for other doctors and performing tasks that don’t put them in direct contact with COVID-19 patients.

Still, Casals has been reading up about the coronavirus and closely following the updates from New York’s overwhelmed hospitals. When he first called his parents to tell them the news, he could “hear the concern in their voices,” he says. His father, Wilfredo, says the family considered trying to get Randy to come home to Pennsylvania, but supports his decision to begin work early. “I told him, Mijo, you’re a soldier in a white uniform. This is like a biological war, and you all are like the soldiers on the frontlines of this,” Wilfredo says in Spanish. “Now he’s going to be a real doctor who can really help others. We’re scared of course, and we’ve told him to protect himself, to take care of himself, but we’ll see how that goes.”

Beyond safety concerns, many medical students say they are nervous about diving into what could essentially be their first year of residency several months early. “The intern year in emergency medicine is exhausting. And just getting through 12 months of it is a lot,” says Benjamin Asriel, a fourth-year student at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine who decided to graduate early but will not be going to work right away. “Everyone in the health care system is trying to figure out how we can work hard and also continue to work in a way that is sustainable.” Asriel is spending these weeks coordinating his school’s volunteer response to the pandemic.

Bernice Fokum, 28, is also wrestling with what it means to start her medical career during COVID-19. After graduating from Atlanta’s Emory School of Medicine, she will start an emergency medicine residency at the University of Chicago. If the hospital calls her and asks her to come before her scheduled start date this summer, Fokum says, she would feel conflicted. She’d be worried about potentially being exposed to COVID-19 and giving it to her parents, with whom she has been living since Emory canceled in-person classes. “I would feel very pulled to be of service in any way that I could,” she says, “but definitely not without fear. Even saying that right now gives me a little shake.”

Fokum is also worried about translating her education to serving patients in an unprecedented pandemic. There is “that feeling of, ‘Are you sure you want me right now?’” she says. “We can’t necessarily prepare the way we would have been able to prepare for someone coming in for a heart attack. This one is so new.” Even veteran doctors, she notes, don’t know exactly how to handle COVID-19—so how can they teach her and her fellow interns?

UMMS Chancellor Dr. Michael Collins says the medical education system was designed to serve students to take on challenges like this one. “It’s a time-honored tradition in medicine that those who are more experienced nurture the careers of those who are less experienced,” he says. “They would have the exact same responsibilities as they would on day one [of a normal residency].”

In Martin’s experience, that’s true so far. He’s matched with a senior attending physician at UMass Medical Center who is teaching him the basics, before he may be given another assignment within the hospital system. Martin expects he’ll mostly be helping with administrative support, like writing up patient notes and calling in treatment orders, but he says that’s okay. “Right now, I don’t have any of the clinical expertise that those senior doctors have,” he says, “but I can write a mean note.”

Still, Collins admits he’s worried about sending students into situations where they might not have enough protective equipment, and says he’s heard from graduates who are concerned about getting sick, potentially making them unable to start their regular residencies on time. “But our students are ready to go,” he says. “One of the things we teach our students in medical school is to go toward the patient, not to go away.”

As schools on the East Coast are finding ways to manage the surge of COVID-19 patients, they are also sharing information with their counterparts around the country. Each Thursday, a group of medical education leaders from schools in the AAMC hold a conference call where they provide updates, discuss regulatory challenges and debate strategies, including how to handle the pandemic.

In the Pacific Northwest, where COVID-19 started in the U.S. (but where outbreaks have not yet reached the intensity of New York), schools are preparing for their own peak. Oregon Health and Science University has had a program in place to let medical students graduate early for the past few years, but this year it wanted to let those who had matched at its own hospital system start working right away to help with COVID-19. After the school worked through funding and logistical concerns, a handful of graduates will start this month as interns in three departments: emergency medicine, family medicine and anesthesiology. If the virus keeps spreading in Oregon, OHSU may need more students to start early as interns, says Dr. George Mejicano, OHSU School of Medicine senior associate dean for education.

Unlike the situation for many New York medical school graduates, these doctors will be working with the residency teams they were already planning to join in July, Mejicano says. That means they can help with the expected wave of COVID-19 patients this spring and be more experienced when the larger class of first-year residents begins this summer, potentially reducing the teaching burden then.

Right now, though, they are in a holding pattern. Dr. Alix Cooper, who just graduated from OHSU School of Medicine, will start on April 20 as a family medicine resident at the local hospital in rural Klamath Falls, Oregon. The 27-year-old studied in a special rural family-medicine program, and has been working with the hospital’s staff for months, but COVID-19 has raised the stakes. “I am definitely getting more and more nervous as the day for me to start is approaching,” Cooper says.

When COVID-19 hits Klamath Falls, Cooper knows the small town’s existing health care shortages will be stretched. “As soon as people start to get sick, we have a pretty small workforce here with no real backup in the community,” Cooper says.

Mejicano, the OHSU dean, says concerns about burnout are real, and he worries about the mental health of all health care workers right now. But he’s confident that Cooper and other graduates are ready. “These young doctors have already been trained on how to use the equipment, how to put on the gowns and the gloves. They’ve learned how to do this,” he says. “This is not like taking somebody off the street and saying, ‘go to take care of someone.’”

In the past few weeks, Mejicano has had leaders from Tulane University, the University of Michigan and other schools calling to ask his advice on how to best help their students join the workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The first days and weeks of these new residents’ experiences are likely to continue being a mix of emotions. Casals had been planning to reunite with friends from college and high school in the time between graduating Columbia’s med school and starting work, and had planned a trip to Europe.

“I feel the loss of all that joy and that celebration that we would have had with our class as sort of a last hurrah before we head into the workforce and scatter. But at the same time, I feel this need to act,” he says. The unique situation has made everything “feel surreal, like it’s a movie,” he adds. But Casals says he wants to help his mentors and colleagues if he can.

“I think medical school does a good job of putting you in situations where you feel a little uncomfortable and a little unsure. And you just have to be confident and act and know that you’ve worked hard and you have people looking out for you,” Casals says. “Your overall guiding principle just has to be: do the right thing for the people in your care.”

—With reporting by Jasmine Aguilera

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com and Jamie Ducharme at jamie.ducharme@time.com