Stephen Gregory was breathing OK around 8 a.m. on Thursday, April 9. A few days earlier, that Monday, Stephen had tested positive for the coronavirus. The nursing home in which he lived, on the northern border of New York City, moved him to the third floor, where a handful of COVID-19 patients—plus those who were showing some symptoms of the disease—were living in isolation.

He asked one of the nurses for water that morning; though he’d had an up and down fever, Stephen, who’s my father’s brother—my uncle—hadn’t been displaying any great respiratory distress. We thought he’d pull through.

But COVID-19, my family learned firsthand, ravages quickly. At some point that afternoon, his breathing stopped. The nursing home called for an ambulance; the EMTs could not resuscitate him. At 3:24 p.m., April 9, Stephen Gregory—whose lanky moves propelled him to Best Dancer honors at the Park Gardens Rehabilitation and Nursing Center annual Academy Awards ceremony—was pronounced dead, after complications from the coronavirus. He was 68.

COVID-19 has stolen an all-too broad swath of humanity. We’ve lost beloved public figures and educators. Heroic health care workers, many of whom sacrificed their own lives to save others. The essential workers who’ve perished while keeping some semblance of normalcy for the rest of us. They’re mothers and fathers, daughters and sons, sisters and brothers.

This pandemic, however, has taken a particularly cruel toll on homes housing the sick, the old and infirm, the developmentally disabled. Those able to fight the coronavirus least. The Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington housed one of the first documented COVID-19 outbreaks in the U.S.: according to King County health officials, 37 people connected to the nursing home have died with COVID-19 since mid-February. According to a study cited in The New York Times, residents of group homes and similar facilities in New York City and surrounding areas were 5.34 times more likely than the general population to develop COVID-19, and 4.86 times more likely to die from the disease. A nursing home in rural North Florida has become a latest coronavirus hotspot: more than 50 people have tested positive, including at least 30 members of the staff.

COVID-19 has stolen people like my uncle Stephen, who spent his life suffering from mental illness. He existed in the shadows of society, largely forgotten by all except his immediate family and those who cared for him, daily.

“We’re heartbroken about this,” says Karen Baratta-Rodriguez, recreation director at the Park Gardens Rehabilitation and Nursing Center in the Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx, where Stephen lived since 2014. Baratta-Rodriguez, whom he’d call “Sharon”—Stephen called my mom, Susan, “Cathy” for years—also knew Stephen from a prior nursing home stop in the Bronx. “The residents are shocked,” says Baratta-Rodriguez. “Stephen was very popular, very sweet, very full of life.”

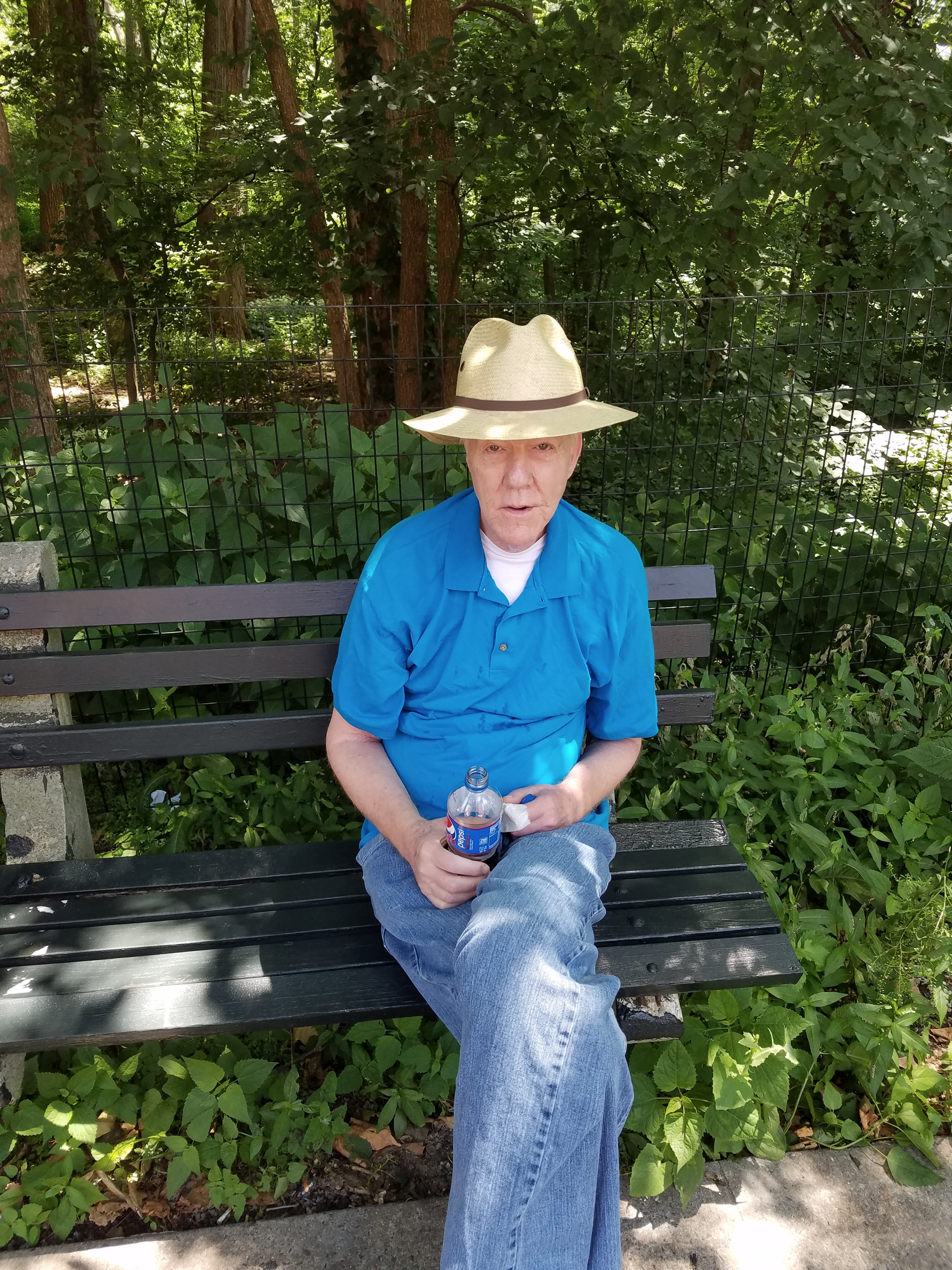

He was fond of disco dancing around Park Gardens in a straw hat, singing “To Sir With Love” at karaoke, and calling one of the physical therapists his girlfriend. He drew pictures for staff members and residents. “Social Worker,” Stephen addressed one piece of artwork to Georgia Thomas, indeed a Park Gardens social worker. “Happy Halloween. Love, Stephen.” He drew a bunch of squiggly orange lines and something that resembled a lion. Thomas hung it in her office.

“Everyone was going to get their artwork from Stephen,” says Baratta-Rodriguez, “even if they didn’t want it.”

At the family Christmas Eve gathering my wife and I have hosted at our apartment in recent years, Stephen was famous for suddenly unfurling his 6’4″ frame off the couch, and breaking into a jig to some Christmas jingle on the radio. And for sneaking out onto the catwalk to bum a cigarette off of Cathy. (The nursing home wouldn’t let him smoke).

“I always felt that under the veneer of any mental disability or struggle was just this really sentimental, fun-loving guy,” says my cousin Andrew O’Connell, another of Stephen’s five nieces and nephews. Andrew remembers Stephen’s fluctuating weight: Although he was noted for eating every pickle and lump of coleslaw in front of him at the diner—his younger brother Michael once said Stephen “had the constitution of an ox”—he could be maddeningly stubborn and refuse to eat the food his caretakers gave him. “There would be years at Christmas where the poor guy would be up there dancing around with his pants falling off his waist,” says Andrew. “But hell, he didn’t seem to mind. He was having a good time.”

Stephen grew up in Parkchester, a sprawling Bronx housing development constructed in the early 1940s; he and his six siblings lived in a two-bedroom apartment. His nickname was “Clowny,” given his reputation as a class prankster. He had a bushel of red hair, and when he’d later shoot jump shots from the corner in the playground, people started calling him Bill Walton.

Once in high school, severe mental episodes struck Stephen: He was once found running on the shoulder of I-95, claiming the people were chasing him and that bugs were crawling all over him. He became prone to violent outbursts, and struck my grandmother on several occasions. (Thankfully, she was never seriously injured). His younger sister Anne—who would go on to become the all-time leading scorer and rebounder in Fordham University history and play basketball professionally in France before starting her career as a high school guidance counselor—sometimes slept in her clothes, in case she had to run out of the apartment in the middle of the night to escape an outburst.

He was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Even while battling his worst demons, Stephen saw to it to buy gifts for his family: When Anne was in grammar school, he bought her a ’45 record of Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay.” It remains one of her favorite songs.

Psychiatric medications tempered his outbursts and calmed his mind. He apologized profusely to Anne for going after my grandmother, even as she assured Stephen that it wasn’t his fault. Stephen eventually took up Off-Track-Betting as a hobby. Once, when a local priest visited Stephen while he was in the hospital with an ear infection, Stephen asked him to bless his OTB ticket. His horses won that day.

Stephen spent the majority of his adult life under state care. For awhile, he lived in a massive psychiatric hospital; he was happiest as part of a program in which the state paid a family to house two or three people with mental impairments. During the day, he’d work a job that kept him occupied and engaged. But that program ended for Stephen, so he had to enter nursing care for the last 15 or so years of his life. He couldn’t leave the nursing home unless someone signed him out. And while my aunt Anne and my father, Chris, were devoted to taking him to the diner or to Dunkin’—he liked buying chocolate munchkins for the nursing staff—Stephen still lived a lonely existence.

When I called two of my cousins to talk about Stephen’s passing, they both shared, unprompted, their guilt. For not visiting him at the home more often, for being content to pretty much see him once a year, on Christmas Eve. “I’m really kicking myself,” says James O’Connell, a New York City public school teacher who lives in Queens. “How hard would it have been for me to get in the car and drive 25 minutes over to Riverdale to see him?”

If James is kicking himself, I’m holding a hammer over my head. Stephen and I lived in the same neighborhood. Park Gardens is a two-minute drive away from me. It’s essentially across the street from where my oldest son played dozens of Little League games. I could have brought him and his younger brother by the home on occasion, to brighten Stephen’s day. And I never visited my uncle in the nearly six years we lived near each other. Not once.

But at least Stephen had a family who cared for him, relatives he could entertain on Christmas. At least he had Social Worker, and the rest of his nursing home staff, to engage with. At least he had friends to flirt with. Despite overseeing a facility overcome by fear of the coronavirus, and despite worrying about their own safety, his health care workers looked after him, until he took his final breath. COVID-19 has taken an untold number of people far more forgotten than Stephen Gregory.

That’s something we can’t ever forget.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com