When pastor Frank Carl delivers a sermon at Genoa Church in Westerville, Ohio, he typically hears a chorus of “amens.” On Sunday, he instead heard a deafening blast of honks.

And Carl wasn’t at the pulpit—he was about 25 feet off the ground on a scissor lift. “It’s not what I had in mind when I accepted a higher calling,” he told TIME of the experience, laughing.

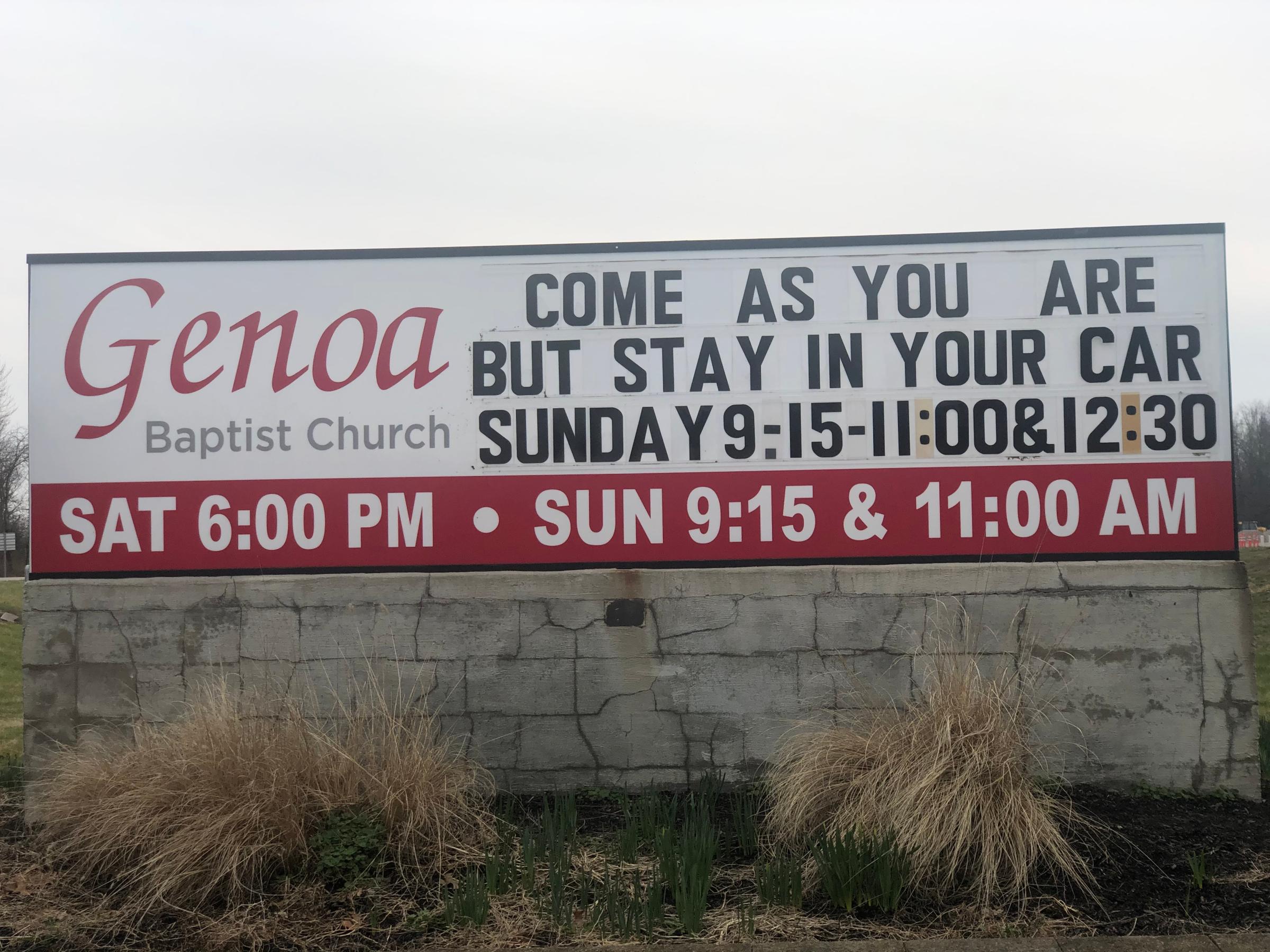

This bizarre method of preaching wasn’t carried out for the sake of vanity or experimentalism, but rather as a compromise in the face of restrictions caused by a virus that has upended virtually every part of life around the globe. As the COVID-19 virus has rapidly spread, public health officials and governments have limited large group meetings and advised everyone to socially distance. But for many churchgoers, communal congregations have become all the more important during a global pandemic.

“I’ve never seen a hunger like this among people for prayer,” Tim Lucas, the lead pastor of Liquid Church in New Jersey, says.

To continue providing services, churches have employed a variety of digital alternatives like livestreams, apps and YouTube videos. But over the past week, an increasing number of pastors have turned instead to a seemingly old-fashioned option to gather their flock: the drive-in. Churchgoers are driving into church parking lots, pulling up a respectable distance away from the next car, and tuning into their radio to hear their pastor speak from the church steps. Meanwhile, drive-in theaters that aren’t allowed to show movies are instead opening up their gates to local churches. These makeshift sessions have left audiences feeling invigorated.

“It wasn’t just one person sitting in a house, looking at a screen. There was that feeling again of having a family,” Yolanda Obaze, who attended the Sunday service of Bethel Church in Evansville, Ind., says. “It felt good to know you had people around you. It was exhilarating.”

But the drive-in church service may not be a lasting solution, as a rising number of states issue stay-at-home or shelter-in-place orders. There’s a lot of grey area involved: states have varied in deciding whether religious ceremonies are essential services; infectious disease experts have different opinions about the risks involved; and it’s unclear whether a phalanx of people in cars meets CDC regulations for social distancing. As Easter rapidly approaches, pastors across the country are scrambling to figure out how they might be able to continue to preach for their honking steel-and-glass congregations.

“I prefer faces, not windshields”

Drive-in church services are not at all new in the United States: Reverend Robert Schuller popularized the form in the 1950s in Garden Grove, Calif., with his Crystal Cathedral, and churches still offer them around the country.

“I grew up on a farm with a retired schoolteacher who made me watch Robert Schuller,” Frank Carl says. When coronavirus began to spread, Carl was inspired to try it for himself.

“It keeps them in a safe environment, and lets them feel like they have some sort of control over this time when we feel so helpless and isolated,” Carl says. Ostensibly, getting in your car, going to a drive-in service, then driving away while never leaving your vehicle would carry a low risk of transmission—lower than shopping at a grocery store, say, or walking on a crowded street. Carl says he reached out to the office of Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and got their approval to move ahead. (A representative for the governor declined to comment.)

On Sunday, 300 cars carrying roughly 600 parishioners arrived in the Genoa church parking lot, amounting to about 40% of its typical weekly population. Carl preached from a scissor lift and was broadcast over a low frequency FM station, which the congregation tuned into in their cars.

As always, Genoa’s service included choral music; the audience was still audible as they sang along in their cars. “We could hear some of them singing. A couple of them, I wish I couldn’t hear,” Carl says, laughing.

The same week, the leadership team at Double Springs Baptist Church in Taylors, S.C., had a similar idea to host a drive-in. Pastor Keith Mincey stood not in the sky but on the sidewalk. It still took him a while to get acclimated to the peculiar new atmosphere. “I prefer faces, not windshields,” he says.

Mincey settled in in front of his fleet of 40 cars, and now sees the benefit of the setup as opposed to just livestreaming his sermons. “For a generation of older people, congregating online is not a community,” he says. He has become interested in continuing to use the drive-in method even after the coronavirus threat has subsided, in the hopes that it could encourage shy newcomers to listen in.

“To walk in a place and enter a group cold turkey is very difficult,” he says. “I’m talking with my staff about how we can, even after this pandemic, still use this as an arm of the church—to maybe have the service both inside and outside at the same time.”

While the services at Double Springs and Genoa were relatively low-tech, low-budget events, Bethel Church in Evansville, Ind., took things up a notch. In the week leading up to Sunday, pastor Dr. Prince Samuel contacted a lighting and stage company that was unbooked due to the cancellations of concerts. The company set up a stage, a speaker system, and a huge screen that projected Samuel to the back row.

Yolanda Obaze, who was sitting in her car, says the technology wasn’t perfect: “There were some glitches,” she says, laughing. But she didn’t mind: “I’m a single person here in Indiana—I literally have almost no one. To know that a church is saying, ‘In spite of what’s going on, we are going to do as much as we can and are thinking of you—that says a lot.”

Obaze is the type of person that Samuel had in mind when he chose to invest in a legitimate live experience as opposed to a digital stream. “We recognize there’s a real mental health component to this,” he says. “With isolation comes depression, anxiety and fear. While we may not be able to shake hands or give each other hugs, it’s still important to get as close to the community as we can, for people’s health and well-being.”

Elaine Howard Ecklund, a sociology professor and the director of the religion and public life program at Rice University, says that a church’s impact on individuals can go far beyond the spiritual realm. “We have to understand how dire this situation is for some churchgoers who get a lot of their social, emotional and even economic support from congregations,” she says. “For some in dire circumstances, for them to not physically see people might feel more risky than the virus itself.”

Booked back-to-back-to-back

As these select churches tested out their makeshift setups, word spread rapidly to other churches across the nation, who began to throw together their own drive-in plans. Outdoor Ultimate Entertainment, an Austin-based company that rents out giant movie screens for events, says that they’ve received more than 30 requests from churches in the last week, and have completely sold out their inventory of LED screens for Easter morning.

Bob Deutsch, the president of Outdoor Movies, has seen a similar uptick in inquiries about drive-in screens, which has been surprising especially in the wake of the mass cancellations that preceded the bump. “Our business has been impacted negatively, but I am surprised by the strength of interest in what we do,” he says. “The inquiries are flowing in.”

While many churches are bringing the drive-in to their parking lots, others are simply going to the drive-in. Preston Brown, the owner of the Hounds Drive-In Theater in Kings Mountain, N.C., was preparing for the theater’s spring season opening when a pastor reached out to him and asked to use his space for Sunday services.

Brown was amenable to letting them use his space for free, partially because he can’t screen movies during the day anyway due to natural sunlight, and partly because it was just a no-brainer: “It was the least I could do in these hard times,” he says. This weekend, a total of 15 churches will arrive over the two days.

66 Drive-In Theatre in Carthage, Mo., isn’t operational in the way Hounds is: Last week, governor Mike Parson banned gatherings of more than 10 people, so the theater hasn’t opened for the season. Nathan McDonald, the theater’s owner, mulled different uses for the space, including holding swap-meets, before reaching out to his friend David Fowler, who is a pastor at the First United Methodist Church of Carthage.

The first service, two Sundays, ago, brought in more than 100 cars. Fowler, who was also inspired by Robert Schuller, preached from atop the concession stand. The service was received enthusiastically, and now the 66 Drive-In Theater is fully booked with a bevy of churches throughout each weekend.

“This Sunday, I’ll start at 8:30 in the morning, and then we have slots back-to-back-to-back until 7 at night,” McDonald says. “I give each pastor an hour, and leave myself 30 minutes in-between to make sure they all get out, or if I have to clean up anything.”

For McDonald, these services represent both a good deed and a shrewd business move, even if he’s not charging the churches. “If this thing carries into the summer and my business is still not operating, I’m supporting the community—and the community will turn around and support me,” he says.

The fact that 66 Drive-In Theatre can host church events but not movies raises the question of whether such church services should be allowed to happen in the first place. Some governors, like Ohio’s Mike Dewine, have stressed the importance of churches remaining open in times of need. California’s stay-at-home order classified “faith based services that are provided through streaming or other technology” as an essential function. Drive-in services, which would go against any stay-at-home order but also seem to follow Centers for Disease Control (CDC) regulations for social distancing, represent an ambiguous area that most states have yet to comment on. (A representative for the CDC did not respond to a request for comment.)

Each of the pastors and drive-in owners interviewed say they are administering strict rules: no getting out of cars; bathrooms are closed except for emergencies; churchgoers are encouraged to text offerings rather than passing around an offering plate.

But McDonald says that after one service last Sunday, some church members couldn’t resist getting out of their cars. “Like true church folks, as soon as it was over, they opened their doors and all got out and started congregating,” he says. “I was like, ‘Listen. You’re missing the point here.’”

Reached by phone, two infectious disease experts had differing opinions on the safety of the drive-in model. “I think it’s a great idea,” William Schaffner, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, says. “It doesn’t bother me as long as someone isn’t driving around in a van, picking up people, jamming them all together and bringing them to services.”

Dr. Krutika Kuppalli, a global health physician and vice chair of the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s global health committee, advises people to just stay home. “It becomes increasingly risky the more people you have in the car,” she says. “Let’s say a woman, her husband, her five-year-old kid and their 70-something grandparent are in the car going to church. You don’t know if the child is asymptomatic, but a carrier. It’s an enclosed space, and the car has multiple high-touch surfaces. The child could potentially could transmit to the grandparent.”

The Easter rush

Whether or not states will continue to allow drive-in services becomes more and more pressing as Easter, the biggest holiday of the Christian calendar, approaches on April 12. McDonald expects that his drive-in lot, which can hold 430 cars, will fill up completely. Samuel, of Bethel Church, has reached out to other pastors and lighting and stage companies in the hopes of putting together a massive drive-in in an open field for Easter.

And Lucas, of Liquid Church, is putting together plans for his own elaborate ceremony: he’s reached out to Outdoor Ultimate Entertainment about renting a massive LED screen; bought thousands of prepackaged, medically sealed communion cups; and has discussed the idea of a prayer team blessing the hood of each car with anointing oil.

“I’m a big believer that every crisis is an opportunity for the church to innovate,” he says. “We already have a slogan picked out: ‘Come as you are in the family car.’”

But New Jersey is currently operating under a stay-at-home order, and religious institutions were not listed by Governor Phil Murphy as an essential businesses. Lucas is waiting on the approval of the local mayor’s office in Parsippany-Troy Hills, without which he will not go forward. “We want to be sensitive to the climate and not do anything that causes any sort of concern,” he says.

Michael Soriano, the town’s mayor, said by phone that he is enthusiastic about the idea but that he is waiting to gain approval from the state. “When they told me about this, my mind exploded with happiness and joy,” he said of Liquid Church. “I’m going to try very hard to see if this can happen.”

Depending on statements from health and governmental officials who are operating in a rapidly-evolving situation, drive-in services may become commonplace across the nation or disappear completely. Either way, they have already had an immeasurable impact on the people who have taken part in them. Sitting in his concession stand in Carthage, McDonald was particularly moved by a sermon given that his mother, who was a devout Christian, died last year.

“I had the radio on, I could hear the preacher up on top, I could hear them playing,” he recalls. “It was a nasty cold rainy morning, I looked out there. He said something good and all the cars started honking. I sat there and let the goosebumps go.”

Please send tips, leads, and stories from the frontlines to virus@time.com.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com