Nobody knows exactly how deadly COVID-19 is, but according to the most reliable and recent information we have, more than 95% of people who get it survive. And though people of all ages have tested positive for the disease, the illness is much more dangerous and lethal among the elderly or those who already have an underlying health condition.

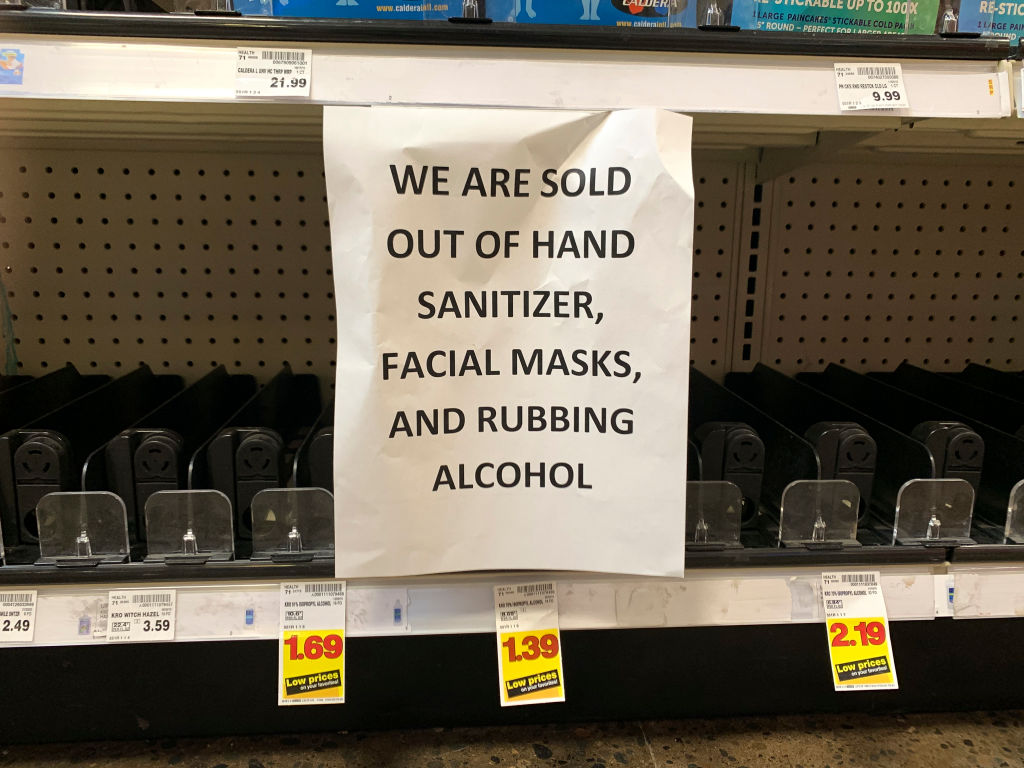

Yet the alarm it has raised, the economic and social disruption it has caused, has been intense. People have cleared shelves of hand sanitizer like it’s a magic elixir. It has dominated the news cycle. The stock market is a rollercoaster. Airline passengers have canceled travel plans, even domestically within the U.S., which has only had deaths in a few states.

In short, people are freaking out. Not all of us have moved from zero to run-into-the-streets-screaming. But even folks who are normally the opposite of anxious have begun to tiptoe into behaviors that are probably alarmist. On average more people die in fires every week in the U.S. than have so far died from the coronavirus illness that has now spread across the globe, yet most people take a much more relaxed attitude toward smoke alarm batteries.

It’s easy to scoff and accuse people of overreacting, but there are ways in which this seemingly irrational agitation is completely logical.

First, experts believe that it’s good to be busy as danger approaches. “Psychologists preach that ‘action binds anxiety’ – in other words, it’s easier to bear our justified pandemic fears if we can think of a few things to do to reduce our risk,” says risk-communications consultant Peter Sandman. Doing something is a brain-distraction technique that enables you to get up and act, to make ready, to grab the nettle, to shake off denial and paralysis.

The problem with COVID-19, however, is that it’s unclear what to do. The disease is spreading fast but may not be any more deadly to the healthy person than the seasonal flu; the scary part is, we just don’t know yet. More broadly, most denizens of the Western world have not deliberated much over the best course of action in the face of a highly communicable and possibly deadly disease. Of the four horsemen of the apocalypse—Death, War, Famine and Pestilence—Pestilence is the one we see the least, shooed off by vaccines, antibiotics and sophisticated sanitation. (The number of nutritional assistance recipients in the U.S., currently 36 million, suggests famine is not as rare as it should be.)

Plus, it’s a novel virus; people have no clue as to what reaction makes sense. Uncertainty is always the ally of panic. “Our guts are way ahead of our understanding,” Sandman tells TIME. “Emotionally, we rightly sense that life as we know it has temporarily changed. But intellectually and behaviorally, the change hasn’t sunk in yet.” And in an era of eroding trust in traditional oracles—the media, the government, the medical profession—people are not sure who to turn to. So they do what most creatures do when they’re afraid and confused; they copy what everyone else like them is doing. At base, we are herd animals; if all our fellow gazelles are running one way, we run that way too, to insulate us from the hazard. When traditional institutions cease to seem trustworthy, people rely on those they do trust, their neighbors and friends.

Moreover, danger is best not faced alone, so if the choice is doing something useful alone (like pressing an elevator button with a knuckle instead of a finger, washing your hands a lot or not touching your face) or doing something of dubious utility but with other people, humans often choose the latter. Or at least both. At the very least, communitarian experiences are comforting.

This is a completely reasonable approach that can lead to some bizarre behavior. When they notice that their friends (and some celebrities) are buying face masks, shoppers clean suppliers out of face masks, despite the fact the World Health Organization has deemed them unnecessary for the general public, and the U.S. Surgeon General has begged folks to stop buying them. They cancel travel plans, even to places that present no immediate risk. They buy up oat milk. They overwhelm home delivery services. They empty stores. More than 100,000 people subscribed to a coronavirus subreddit in one day, but the CDC struggles to get its message out. A third of British people polled between February 28 and March 1 wanted the government to stop all inbound flights from countries where there is a confirmed outbreak of the disease (that’s more than 100 locations around the world, according to a CDC update on March 9—and the U.K already has a few hundred cases).

Then there’s our highly, constantly connected world, with its amplification effect. The more people post images showing that zinc lozenges are sold out, the more their otherwise chill friends worry about getting zinc lozenges. In Australia there was a mystifying panic-buying of toilet paper—weapons were drawn—that led to an even bigger shortage of toilet paper. In China, where social media penetration can be stronger than regular media, conspiracy theories have abounded. “The kind of fear and panic that you see in America now, I would say in China is [magnified] 10 times,” Winnie Chi-Man Yip, a professor of global health policy at Harvard University, told a conference on the outbreak at Harvard on March 2. “People immediately overnight buy up all the medicine, all the masks (which are not needed) and all the food.”

Again, there is logic behind these omnivorous shopping expeditions. What is the downside, people ask, of having extra diapers or dried pasta or disinfectant wipes? It feels like preparedness. It feels like a measure of control. “Many people hold the implicit belief that big problems require big solutions,” says Steven Taylor, a professor and clinical psychologist at the University of British Columbia, and the author of The Psychology of Pandemics. “Yet, they were told that the big problem should be addressed with small, seemingly trivial solutions (e.g., hand washing). So, many people felt that they needed to do more to keep themselves and their families safe. Hence, the excessive shopping.”

It seems smart to have lots of extra toilet paper, because toilet paper doesn’t expire, it will never go to waste, and running out is a calamity. Buying it in bulk does not feel like what it actually is, which is a way of making the situation worse. Those who might actually need the hand sanitizer and less-perishable food and plenty of TP are the frail, already ill and elderly, those who are least likely to be able to rush off to the store. Face masks are most needed by medical professionals or frontline workers; reducing supply for them means a greater likelihood of the virus spreading.

As a species, humans have survived by bullying their way to the top of the food chain, by outwitting predators and by being ingenious enough to withstand disasters. Also, evolutionary psychologists and sacred texts both say, we’ve thrived by communicating and working together. The species looks likely to withstand this novel threat as well, but perhaps at some cost to our common sense.

Here’s what you need to know about coronavirus:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com