As people around the world celebrate International Women’s Day — an annual March 8 observance — countries from Kyrgyzstan to Cambodia will officially honor women’s rights and achievements across the political, economic, social and cultural spheres. The day has been designated as an official United Nations observance since 1975, which was International Women’s Year, and is a national holiday in many parts of the world.

But the day’s origins go much further back than 1975 — and are more radical than what we might expect from a day so widely celebrated.

Centering around the socialist movements of the early 20th century, here’s more on the history of how International Women’s Day (IWD) came to be:

How did International Women’s Day start?

The impetus for establishing an International Women’s Day can be traced back to New York City in February 1908, when thousands of women who were garment workers went on strike and marched through the city to protest against their working conditions. “Like today, these women were in less organized workplaces [than their male counterparts], were in the lower echelons of the garment industry, and were working at low wages and experiencing sexual harassment,” says Eileen Boris, Professor of Feminist Studies at the University of California Santa Barbara.

In honor of the anniversary of those strikes, which were ongoing for more than a year, a National Women’s Day was celebrated for the first time in the U.S. on Feb. 28, 1909, spearheaded by the Socialist Party of America.

Led by German campaigner and socialist Clara Zetkin, the idea to turn the day into an international movement advocating universal suffrage was established at the International Conference of Working Women in 1910. Zetkin was renowned as a passionate orator and advocate for working women’s rights, and her efforts were crucial to the day’s recognition throughout much of Europe in the early 1910s.

The most consequential International Women’s Day protest

Although International Women’s Day had started with action from the women’s labor movement in the U.S., it took on a truly revolutionary form in Russia in 1917.

Just as Zetkin’s idea was spreading through Europe, Russia (where International Women’s Day was established in 1913) was facing unrest for other reasons too. It was against the backdrop of a country exhausted by war, widespread food shortages and escalating popular protest that the nation’s 1917 International Women’s Day demonstration was held on Feb. 23 of that year — the equivalent of March 8 in the Russian calendar, indicating the significance of the date of the commemorations today.

Though it wasn’t Russia’s first International Women’s Day, historian and activist Rochelle Ruthchild of Harvard’s Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies points to the differences between earlier protests and this demonstration, which took place in the then-capital Petrograd and involved thousands. “Women were mostly the ones on the breadline, and were the core protesters,” she says. “In fact, male revolutionaries like [Leon] Trotsky were upset at them, as these disobedient and misbehaving women were going out on this International Women’s Day, when they were meant to wait until May,” referring to the annual worker’s protests on May 1.

Despite the initial directives from revolutionary leaders, the protests that began on March 8 grew to daily mass strikes of workers from all sectors demanding bread, better rights and the end to autocracy. A week later, the Tsar abdicated, signaling the downfall of the Russian Empire and paving the way for socialism and the formation of the Soviet Union in 1922.

“You could argue that these demonstrations sparked the abdication of Tsar Nicholas and the end of the Romanov dynasty,” Ruthchild says. “This was probably the most consequential of any International Women’s Day demonstrations of any time.”

Suffrage and International Women’s Day

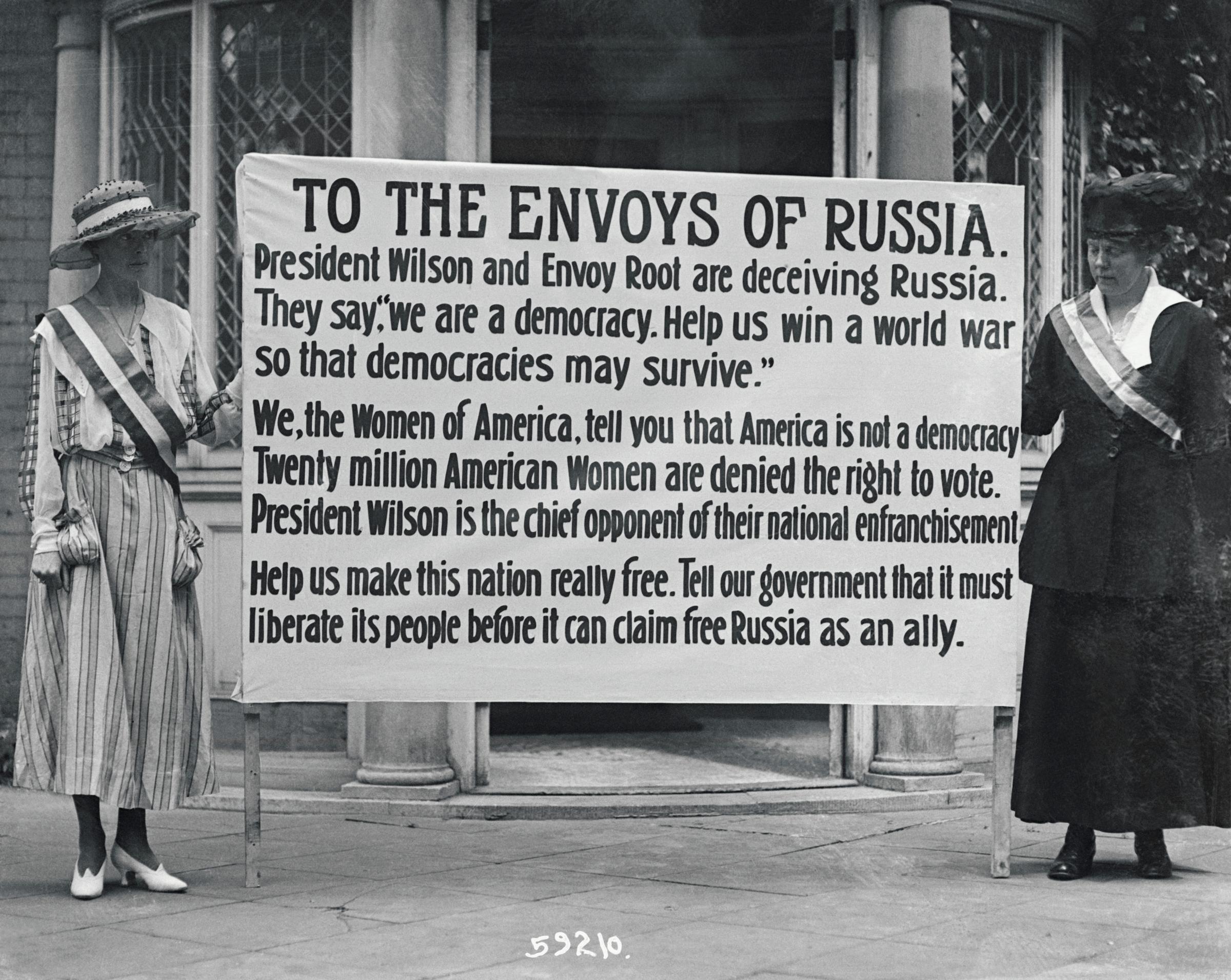

Russian women demanded — and gained — the right to vote in 1917 as a direct consequence of the March protests and after more than 40,000 women and men again took to the streets demanding universal suffrage. This made Russia the first major power to enact suffrage legislation for women, a year earlier than Britain and three years earlier than the United States. In fact, suffragettes in the U.K. and their counterparts in the U.S. both looked to Russia as an example, and held what they saw as the country’s progress and liberation of women up as a mirror to their own governments, warning that they were lagging behind.

“Women’s movements, be it suffrage or labor rights, have always had an international connection,” says Boris. British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst visiting Russia in June 1917 and the creation of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom during World War I are examples of these early 20th century global links.

However, the celebration of International Women’s Day itself did not hold as much weight in the U.S. through the 20th century as it did in other countries, largely due to its political associations with the Soviet Union and socialism amid increasing Cold War tensions. The fact that an official U.N. day observance was only established in 1975 underlines this point, and may go some way to explaining why the day still isn’t as widely recognized in the U.S. today as it is elsewhere, though it is no coincidence that March is the nation’s Women’s History Month.

“I think it’s really interesting that all over the world, people observe this day that actually originated in the U.S.,” says Ruthchild, “but the U.S. doesn’t observe it to the same degree.”

‘Many more steps to take’

In the century since it was first established, International Women’s Day has come to be marked just as frequently with celebration as it is with protest, but the day’s legacy remains steeped in the struggle for women’s rights — an element that has gained renewed relevance in recent months, particularly as the #MeToo movement has taken on global dimensions.

Looking to the history of International Women’s Day today in Russia, Ruthchild points out the “irony” of recent developments in laws affecting Russian women; for example, last year Vladimir Putin signed a controversial amendment to a law that decriminalized some forms of domestic violence. “How did a society which touted women’s liberation turn so quickly into a society that has reacted so strongly against notions of women’s equality and women’s rights?” she says.

And Russia is by no means the only country where women continue to face challenges to their rights. “Certainly, there are people and leaders in the U.S. who would like to turn back the clock too,” says Ruthchild. In the time since President Trump’s election in 2016 and the Women’s March in early 2017, American women have been mobilized to action by conversations surrounding sexual harassment, equal pay, threats to reproductive healthcare and more.

International Women’s Day doesn’t seem likely to lose its radical flavor any time soon.

“Days like IWD are a time to celebrate the gains that have been made and to measure how far we have come,” Boris says, “but also to see that there are many more steps to take and to rededicate to the struggle ahead.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com