Kayla Cook has the zeal of a convert.

The 18-year old freshman at University of Northern Iowa grew up in a Republican family, was raised by a Trump-supporting mother, and still identifies as a moderate conservative: she’s a devout Christian, pro-life, and skeptical of big government. But underneath the small silver cross she wears around her neck, Cook is sporting a sweatshirt promoting South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s presidential candidacy and three blue-and-yellow buttons proclaiming PETE.

“I talk to people about Pete all the time,” she says over Subway sandwiches a few blocks from a Buttigieg campaign event in Vinton, Iowa on Monday. Alexis Miller, Cook’s friend and fellow student, confirms and rolls her eyes. “No, seriously, every conversation that we have, Pete comes up,” Miller says.

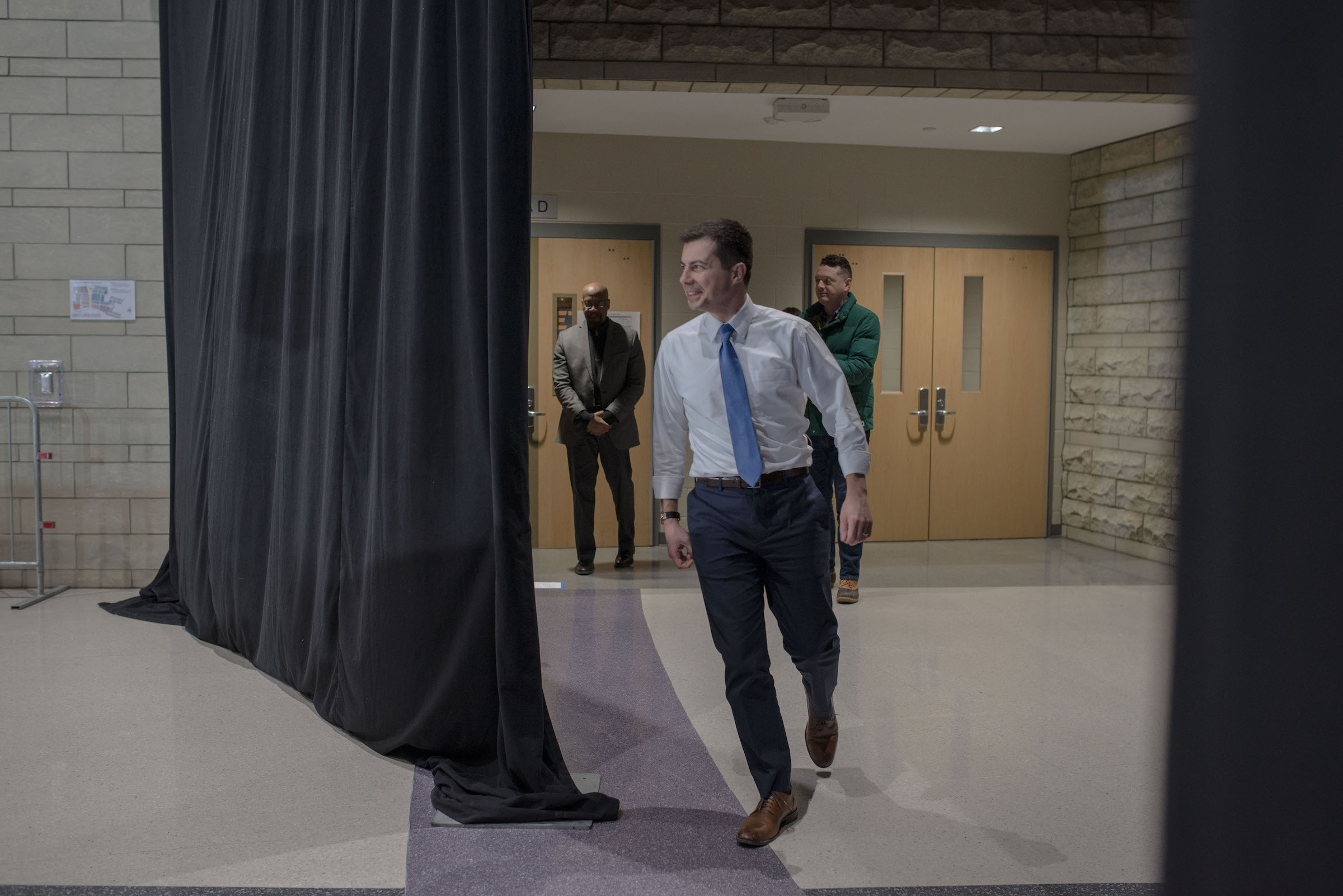

Cook’s enthusiasm for Buttigieg sets her apart from most Americans her age, who tend to overwhelmingly support Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders or his progressive rival, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren. But Cook—and conscience-stricken conservatives like her—are key to Buttigieg’s bet in both Iowa and across the country. In stump speeches and campaign materials, Buttigieg has consistently targeted voters who identify as moderate or conservative, or those who worry about supporting a Democrat who would alienate their conservative neighbors. Buttigieg is fond of talking about his plan to heal a “crisis of belonging,” which includes reaching out a hand to what he calls “future former Republicans.”

Of course, it’s impossible to know just how many “future former Republicans” like Cook are actually in the Buttigieg camp. Trump’s popularity has remained stubbornly high among conservatives, and there’s little evidence that Republicans will defect from the GOP in strong enough numbers to swing the election, let along participate in a Democratic caucus. But many of Buttigieg’s supporters like the idea that he could appeal to Republicans, even if it’s not yet clear that he definitely will.

“Most of our friends out here are Republicans,” says Sharon Scherrer, a 52-year old foreign exchange student coordinator and Buttigieg supporter who saw him speak in Vinton on Monday. “I just want someone who takes their views into account. They’re not going away.”

Scherrer says that while many of her conservative neighbors get riled up against more progressive Democrats, Buttigieg hasn’t attracted their ire yet. “I see constant posts from people who hate Bernie and Warren,” she says. “I never see negative stuff about Pete. That makes me feel like these people can be placated, and we can get back to some kind of peace.”

The potential to appeal to moderates and disaffected conservatives is central to Buttigieg’s pitch, even if there’s little evidence that Republicans will actually jump ship. Even as the progressive left sharpens their knives to attack him as insufficiently liberal, the 38-year-old mayor has peppered his stump speeches and public appearances with olive branches to Republicans, moderates, and folks like Cook, who otherwise identify as conservative. Campaign spokesman Ben Halle calls it a “message of unity,” adding that a former Republican introduced Buttigieg at his Indianola event on Tuesday.

“While he has a very liberal platform, he has a moderate temperment,” says Tim Miller, a writer for The Bulwark and former Republican strategist who was a spokesman for Jeb Bush’s 2016 campaign. “He respects the military, he’s talking about respecting the rule of law, he talks about his sexuality from a traditional values manner. So in that sense there’s a kind of a comfort there for ex-Republicans who feel alienated from their home base.”

“I don’t think that you have to be a Democrat to see what is wrong with this Presidency,” Buttigieg said in a Fox News town hall on January 26. “My message is that we can at least agree on this: that if you’re having trouble looking your kids in the eye and explaining this presidency to them, then you have a choice.”

That’s exactly what Cook is looking for. Like many young conservatives, she believes in marriage equality and thinks the government should act on climate change, but is wary of major government intervention in the economy. She believes the Trump administration does not represent either the country or the Republican party. “We’re better than that,” she says. “I’m a Christian, and the current president does not represent my faith at all. I want someone who shares my values…I can’t look at the President and be like, ‘This is okay.'”

In November, Cook brought her mother, a Trump supporter, to a Buttigieg rally. Her mother’s conclusion? He’s “not stupid”—a remarkably positive assessment, Cook says. It’s “a big deal for her to say a nice thing about a Democrat,” she says.

“The independents and the Republicans who have been coming to meetings are all for Pete,” says Laura Hubka, the chair of the Howard County Democrats who supports Buttigieg. “They’re saying they won’t flip for Bernie or Warren but they say they would flip for Pete.” Howard County, a tiny rural county on the Iowa-Minnesota border, swung 41 points from Obama to Trump between 2012 and 2016.

The Democratic base appears to be leaning in a different direction. As Warren relies on a superbly organized Iowa ground game and former Vice President Joe Biden holds a consistent lead bolstered in part from his association with the Obama administration, Sanders has soared to the top of the polls partly because of his popularity with young voters. According to recent polls, the Vermont senator and self-described democratic socialist is now among the top two candidates in both Iowa and New Hampshire. “I don’t get it,” Cook says. “I feel like Bernie supporters don’t represent the average American.”

For other moderate Buttigieg supporters, they’re worried the progressive candidates’ embrace of Ideas like Medicare for All will make it harder for them to win in a general election. “I know too many people who are just so wholeheartedly against those ideas that they would vote for Trump,” says Jennifer Smentek, a 47-year old social worker who saw Buttigieg speak in Vinton. “I think they’re too progressive,” she says of Warren and Sanders. “I don’t think that they’re electable.”

But mostly, Buttigieg’s supporters say, they just want a return to normalcy. “I am sick, sick, sick of the fighting,” says Scherrer. “I would vote for a snowman.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlotte Alter/Vinton, Iowa at charlotte.alter@time.com