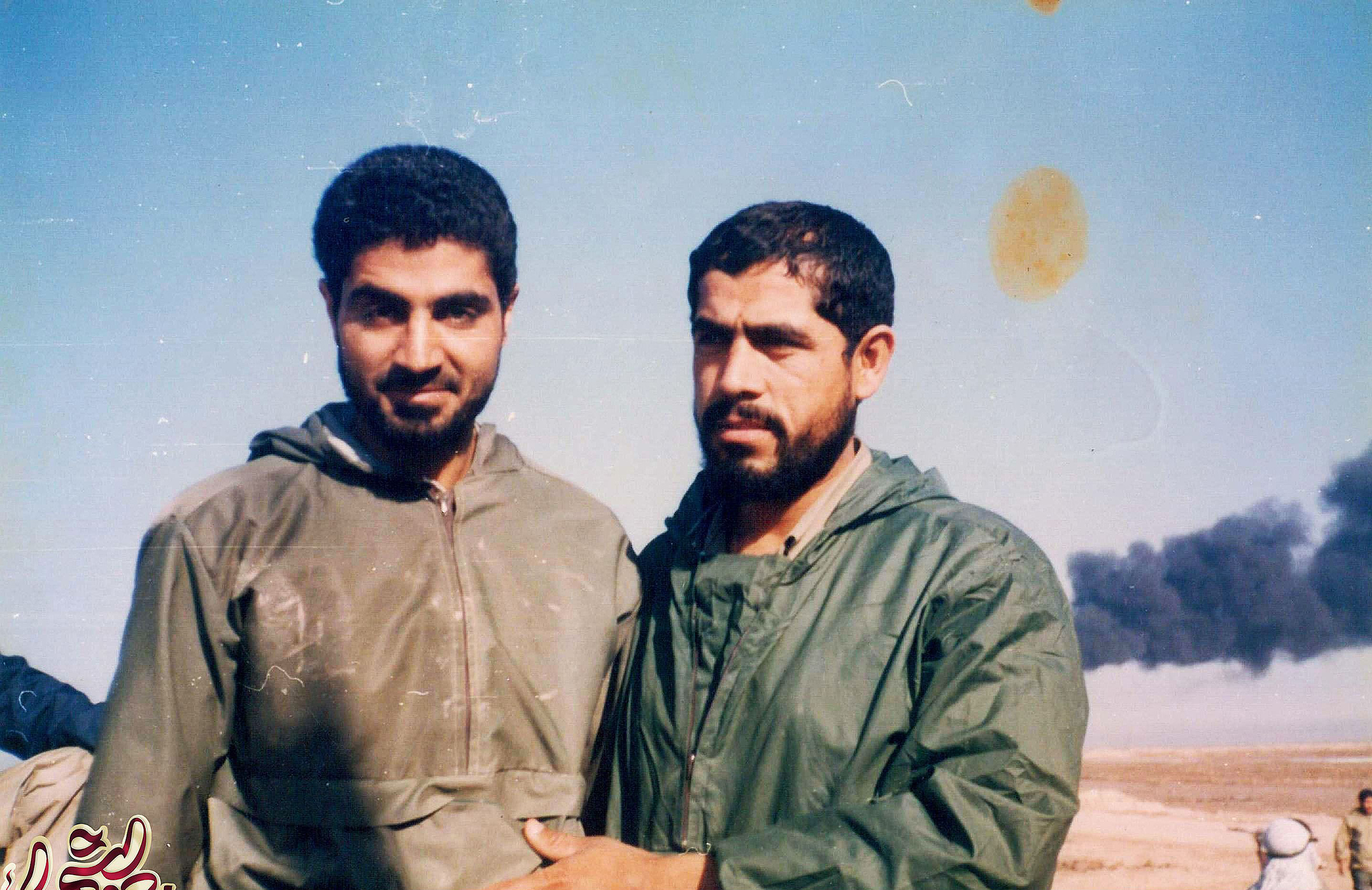

In 1981, at the outset of the Iran-Iraq War, Qassem Soleimani witnessed his country’s first use of human wave-style tactics. That costly practice would become one of the hallmarks of a conflict that would claim nearly a million lives on both sides and would see a return to First World War style trench warfare and the widespread use of chemical weapons. When the UN eventually negotiated a ceasefire, both sides claimed victory. A key result of the conflict was Iran’s adoption of a national security strategy that relied on the more economical practice of asymmetric warfare (terrorism, wars by proxy). The Revolutionary Guards Quds Force, led by Soleimani for more than twenty years, played a crucial role in the implementation of this strategy, which ensured that Iranian society would never again experience such a bloodletting. For leaders in Tehran, the Iran-Iraq War would become “the war to end all wars”—sort of.

Now Soleimani is dead. A lot has been written in recent days about “war with Iran” while far less has been written about what that war might look like. Or acknowledging that, on the battlefields of America’s “forever wars,” a “war with Iran” has been going on for decades. During my time in the Marines, I brushed up against Iranian militias in Iraq in 2004 and 2005, helped Americans evacuate the embassy in Beirut in 2006 when Hezbollah threatened our presence, and then fought Quds Force-supported elements of the Taliban in western Afghanistan in 2008. Nearly a decade at war left me with many dead friends and, when tallying up how they died, I can trace more of their deaths to the barrel of an Iranian-supported Shia militiaman, or an Iranian-developed armor piercing IED, than to card-carrying members of al-Qaeda.

In many respects, both America and Iran have pursued similar national security strategies over the past two decades, enabling the populations of both countries to remain at “peace” while our cadres of military professionals have engaged in wars by proxy and other special operations around the globe. Soleimani’s replacement, Esmail Ghaani, as well as the entire high command, are not only the architects of our low-intensity ‘forever war’ with Iran but they are also veterans of the Iran-Iraq War. Their experience will factor prominently into crafting a post-Soleimani strategy for the region and whether that strategy will lead them into an escalatory spiral that could, ultimately, precipitate a more costly conventional war, upending “peace” at home.

Despite nationalist anger at the death of Soleimani, Iran’s internal politics are as fractious as our own, and those divisions will soon re-emerge, just as our own will if (or when) Iran launches attacks that are more spectacular than their immediate response against Al-Asad air base and Irbil. Both of our nations have little appetite for a protracted conventional war, with anxious Google search terms such as “World War Three” and “the draft” surging in the United States last weekend and widespread protests across Iran throughout this past fall. If there’s a shared appetite for anything, it is de-escalation.

Navigating that de-escalation will be challenging. It will require pragmatism and moderation on the part of Iranian leaders who are enraged, and in mourning. And it will require moderation and precision on the part of an American president who is not known for either of those qualities. However, our decades-long limited war with Iran has yet to spiral out of control. That the formative experience of Iran’s generals was a futile conventional war with few parallels in history, except perhaps the First World War, cannot be emphasized enough. That experience, more than any other, may allow us to avoid further escalation.

Despite the best of intentions and the clearest of strategies, luck always plays a role on the path to war. The days ahead might very well prove as precarious as that calamitous summer of 1914, which led to the First World War. Like with Soleimani, that conflict began with an execution, that of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. The assassin happened to be sitting in a café armed with a pistol when the Archduke’s car took a wrong turn. The Archduke’s fatal mistake seemed so simple, and common, in retrospect: he found himself on a road he never should’ve traveled in the first place.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com