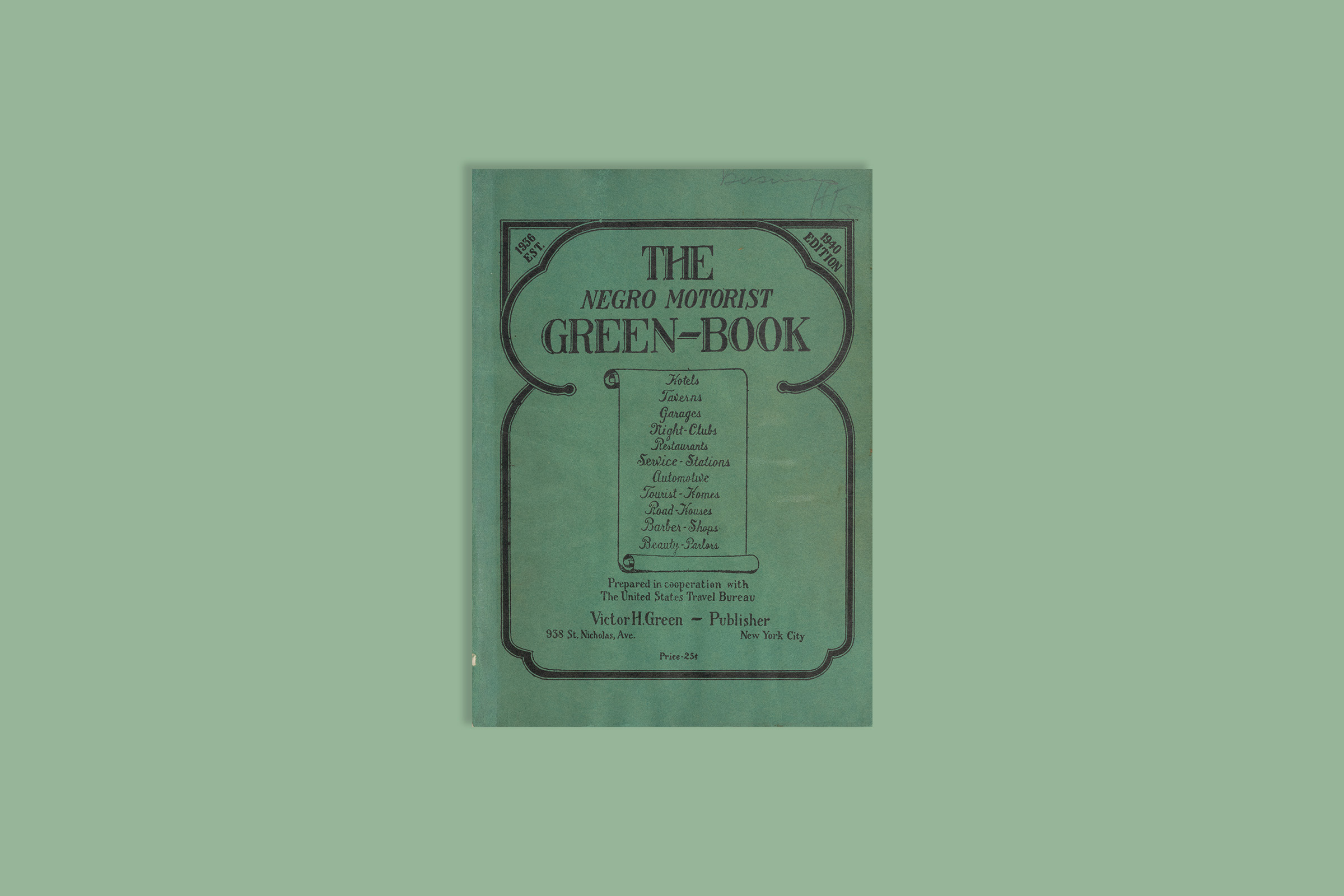

For decades, the Green Book was an indispensable guide to travel for African Americans in the segregated United States. It also played a critical role in the lives of women. Whether they were traveling across the country or running a hotel, beauty shop, tourist home, or even a sex club, the Green Book helped women break out of traditional gender roles. At a time when they couldn’t get credit from a bank or even have their own bank accounts, black women found a measure of success and independence by listing their businesses in the Green Book.

In addition to tourist homes, the Green Book featured traditionally “female” businesses, such as hair salons and beauty colleges. There were just under 900 beauty shops listed in the Green Book during its life. Beauty salons were active, long-standing businesses in a community, providing a safe place where people could sit for hours. Amid the aroma of corrosive chemicals and the clicking of curling irons, customers could let down their hair, literally and figuratively, and spill their secrets in the comfort of cushioned vinyl.

Salon operators were not just hairstylists; they were pillars of the community. During the time salons were listed in the Green Book, some of them served as headquarters for community development, especially during the birth of the civil rights movement. At election time, stylists drove their clients to the voting booth, and since the NAACP was considered a radical organization, some clients had its literature delivered to the beauty shop instead of their homes. And you could usually find a copy of the Chicago Defender sitting on tables in the waiting area or in the magazine racks between hair dryers, next to Jet and Ebony.

Of the 17 beauty schools listed in the Green Book, the two most popular were Madam C.J. Walker’s College of Beauty Culture and Annie M. Turnbo Malone’s Poro Colleges. Malone started the Poro schools in 1917, and although she passed away in 1957, eight of her schools were still listed in the 1959 Green Book. They were scattered throughout the United States, including in New Orleans; St. Louis and Jefferson City, Mo.; and Cincinnati and Cleveland, Ohio.

Walker and Malone revolutionized the black hair care industry by creating unique products to condition, grow and straighten hair, which resulted in unprecedented wealth for both entrepreneurs. They trained thousands of women throughout the nation to use their hairstyling techniques, sell their products from door to door, and run their own businesses. Working for Walker or Malone offered independence, power and freedom from cleaning up after white people. As the automobile industry lifted black men out of poverty and into the middle class, the hair industry did the same for black women.

The Velvatex College of Beauty Culture in Little Rock, Ark., is still in operation. In the early 1950s, its president, Mary Ellen Patterson, who established sorority chapters of the service organization Alpha Phi Omega throughout the state, took her students to do hair for free twice a month at the State Hospital for the mentally ill.

Another remarkable black businesswoman who ran a Green Book business was Ms. Geneva Haugabrooks. She ran a funeral home on Auburn Street in Atlanta. Her husband drowned soon after it opened in 1929, and she never remarried. She began the business with only $300 and kept it going until 1977. During its height, she buried about a thousand people a year. Marcus Wimby—Geneva was his grandfather’s aunt—runs the business today [it was recently sold]. “Ma” Haugabrooks knew everybody in town, he told me. She would sit on the porch and wave at people who passed by and tell them, “I’m gonna get you one day!”

Ma Haugabrooks even had clout with law enforcement. As Marcus remembers, after one of her employees was picked up by the police, when he said he worked for Ms. Haugabrooks, the white police officer didn’t take him to jail. He took him to Ms. Haugabrooks and asked, “What do you want me to do with him?”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

When white supremacists shot up Modjeska Simkins’ Green Book-listed motel at 8:50 pm on March 15, 1956, she wasn’t rattled. It was the second time that week that Motel Simbeth’s neon “Colored” sign had been smashed and littered with bullets. The first time, the perpetrators had not only shot up the other side of the sign, but also fired at the porch, near the office. The Simbeth staff were unable to identify the perpetrators in the dark, and the gunmen (or others) came back the following month and shot up the place again. When reporters came out to cover the story, Simkins didn’t have much to say about white terrorism. Later, in an interview about the Ku Klux Klan, she said, “I don’t even hate the Ku Klux Klan, because if they’re fool enough to do what they want to do . . . just so they don’t come here and step off that sidewalk onto my walkway . . . they can build a cross right out there if they want to, but don’t come up on my porch.”

Simkins didn’t let the Confederate flag upset her, either. “They got that thing up there [at the State House] celebrating the Confederacy. There ain’t nobody in the depths of Africa going to put a rag up there and say we got our behinds whipped, you see?”

Simkins was fearless, outspoken, and knew her history. She was also a highly intelligent woman who taught medieval history and civics at Benedict College. She fought to equalize teachers’ salaries and get bus transportation for those who needed it, and she frequently spoke out against taxation without representation. She organized several South Carolina NAACP chapters and was one of the founders of the NAACP state conference. She then spearheaded a statewide campaign that eventually dismantled the white primary election so that black people could vote. Columbia finally celebrated Simkins in 1991, when the mayor of the city declared December 5th Modjeska Simkins Day.

And these women weren’t the only ones using the Green Book to change their lives and communities.

By the 1959 edition, not only were women listing their businesses, but a woman was in charge of the entire Green Book operation. Alma Duke Green (the wife of founder Victor Green) was now listed as the editor and publisher of the guide, and nearly all her staff members were female. Victor Green acted as an adviser for this edition, but given that he would die in 1960, it’s possible he was too ill and unable to work. In any case, Alma had been right alongside him since he started the guide in 1936—and she was the perfect person to pick up the baton.

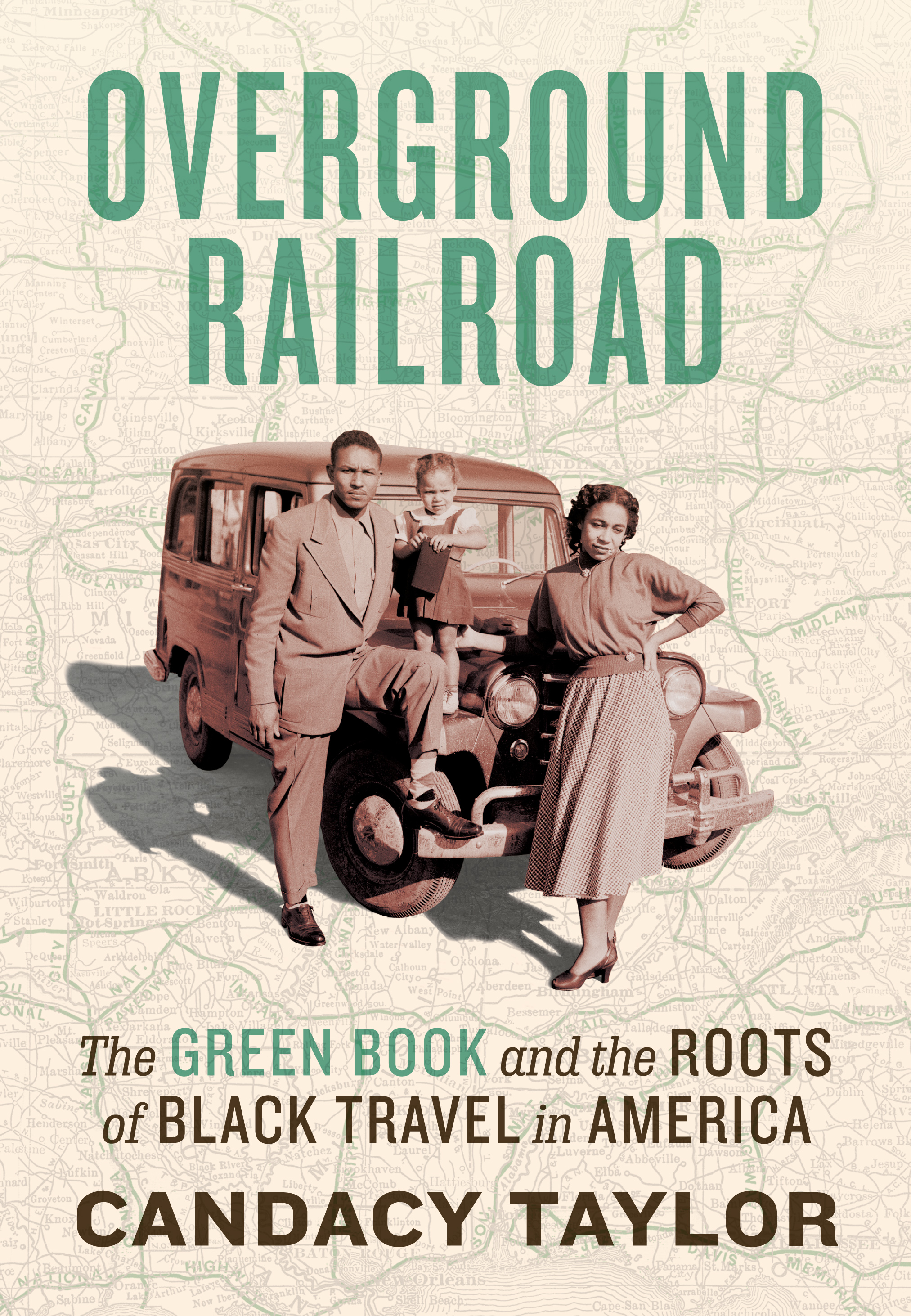

Excerpt from the new book Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America by Candacy Taylor (Abrams Press). Copyright © 2020 Candacy Taylor. Used by permission of Abrams Press, an imprint of Harry N. Abrams, Inc., New York. All rights reserved.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com