In the last few weeks, Twitter has been alight with a new kind of conversation: about friendship. Most of the time, friends bring us joy. (Or at least, that’s the idea about chosen family.) But part of the package is helping people out in times of need — and we aren’t always prepared for that form of emotional labor, no matter how close the relationship.

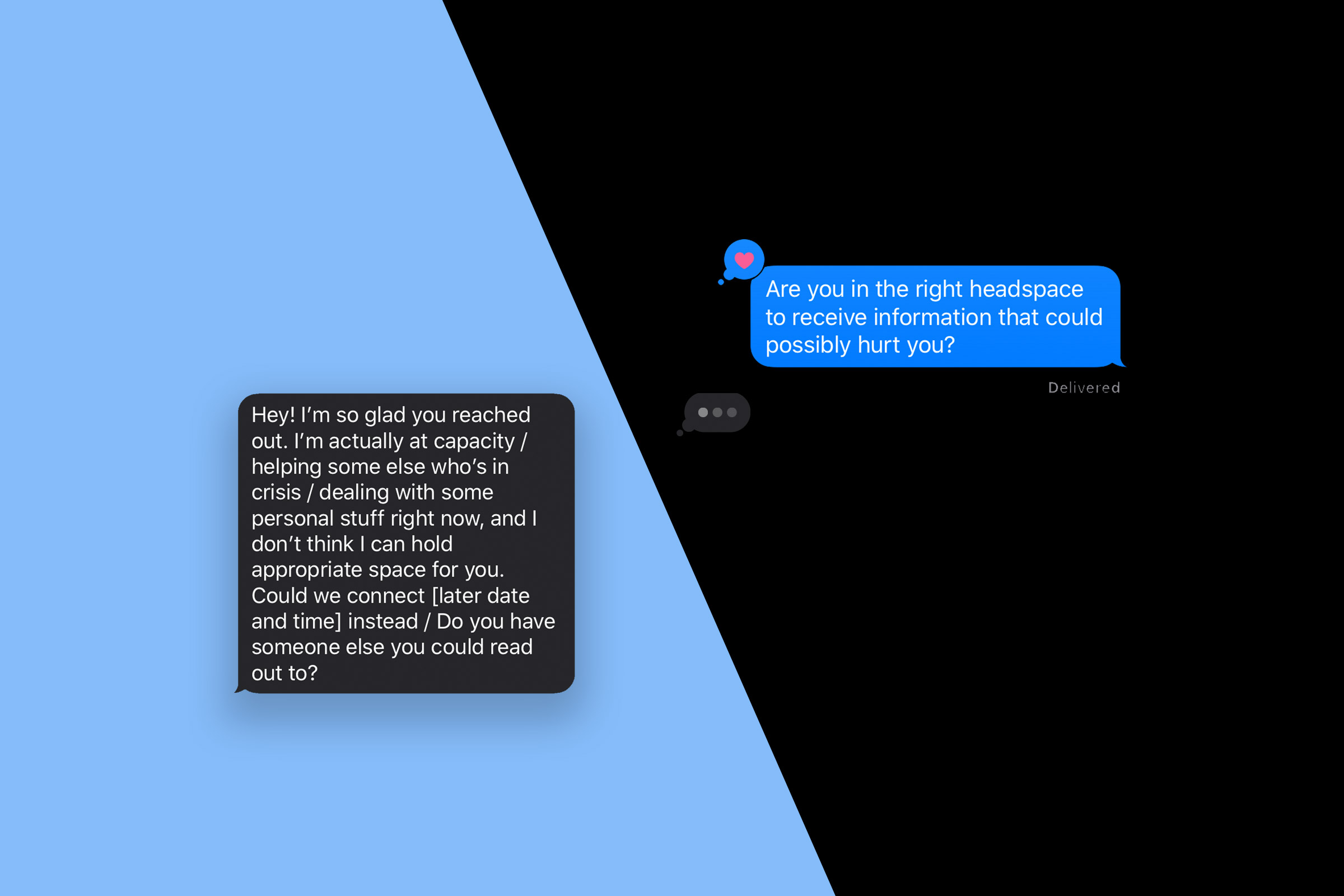

The debate began in November, when activist and writer Melissa Fabello shared the template for a text conversation with friends. In it, she offered a pre-message heads-up about a difficult subject ahead. Eleven days later, another Twitter user, Ayana, shared her own take on how to ask if a friend was “in the right headspace to receive information that could possibly hurt” them.

Their intent? To provide a roadmap for respecting the recipient’s “emotional/mental capacity” when being informed of difficult news, and to offer others a route to avoid unloading anxieties and problems on unsuspecting friends. Ultimately, they were text-based trigger warnings that the women recommended readers incorporate into their friendship practices. Both tweets went viral. But not everyone was on board, with many responses deriding the messages for their clinical nature, and for introducing the concept of “consent” into friendships.

Not everyone disagreed, but there were questions about the suggested phrasing as laid out by the Twitter posters. So what do experts recommend when it comes to sharing hard things with friends — without minimizing the challenges faced on either side of the friendship?

To untangle the questions at the heart of the debate about friendship communication, TIME spoke with Dr. Miriam Kirmayer, clinical psychologist and friendship expert, and Alena Gerst, licensed therapist and integrative health specialist. Both experts agreed: every relationship is distinct, and it’s important to clarify the bounds and expectations of each before you make broad generalizations about how to share personal issues.

“It’s easy to assume that setting boundaries will come at the expense of our relationships, when often it is the very thing that allows us to continue to show up as a present, supportive friend,” Dr. Kirmayer says. Gerst agrees: “I’m of the mindset it’s more considerate to prep people about what they’re about to read or about to see.” That said, if something is “truly urgent,” then “it just needs to come out,” she adds.

So is it appropriate to communicate friendship boundaries in the way the controversial tweets suggest? It certainly can be,” Kirmayer says. She suggests asking yourself two important questions: Is this decision coming from a place of fear? And does this fit into a larger pattern? “I see the strong reactions that many people have had to this conversation as relating to a sense of permanency,” she says. “There will undoubtedly be times when we need to show up for friends when we aren’t in the ideal headspace, just as there will be moments when our friends are unable to provide the support

we seek. It’s only when there’s an ongoing issue related to the exchange of support that it becomes problematic.”

Plus, Gerst sees these pre-message warnings as a part of society trying to figure out how to navigate our many modes of contact. “We’re in a Wild Wild West in the way we communicate, because we have access to our friends in a way we didn’t used to,” she says. “We used to call our friends, and if they weren’t there you just had to hang up. Now nobody calls anymore.” For Gerst, one good way to establish norms is to understand what a call vs. a text means within the context of each relationship: “My friends and I have a system where if one of us calls, it’s urgent and there needs to be a return. Otherwise, we’ll text. If I get a voicemail from one of them, I know I need to drop everything and call.” That shorthand cuts out the need to add a precursor message.

It’s also important to recognize that friendships do take work, and that emotional labor — which is often disproportionately performed by women — is labor. “The effort it takes to sit with a friend hold space for their pain or uncertainty can be challenging,” explains Kirmayer. “Setting boundaries can be an important way to take care of our own wellbeing and to refuel our capacity for empathy.”

The writers of the tweets were onto something: even close relationships require respect and a certain level of maintenance and attention. “Our friends pick up on half-hearted shows of support. Boundaries make it easier to offer our friends the kind of emotional support they need,” Kirmayer says.

But first you need to establish the basics. “Somebody really needs to be sure of what kind of friendship they’re in,” Gerst reminds us. “In my line of work, I talk to people frequently who have friends who think they’re best friends, but they’re not.” You need to be honest with yourself about who the person is and their connection to you before you expect immediate emotional commitment at all times. And then, Gerst says, there becomes a “code” in each friendship that dictates the way you talk and text. A one-size-fits-all approach won’t necessarily work.

Kirmayer suggests following four ground rules in your friendship communication : (1) emphasize your desire and choice to stay connected; (2) know the difference between “ruminating” and “problem-solving;” that is, don’t just re-hash complaints, but work towards actively making progress; (3) recognize when boundaries are necessary; and (4) strive for openness.

Friendships have “far fewer explicit rules” than other relationships, she says, which is why reassessing and adjusting expectations is key. Gerst suggests that online communities — like Facebook groups or group chats — can also be helpful places for people to connect and discuss challenges, which alleviates some of the pressures of one-on-one chats.

So while some detractors may not be a fan of the templates shared in those initial viral tweets, the experts agree that the intention behind them is worthy. “If you’re reading this article or you’ve noticed what’s happening on Twitter, this could be a really good conversation starter,” Gerst says. Ask your friends: how are we doing? You might be surprised by the answer.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Raisa Bruner at raisa.bruner@time.com