The sunken battleship U.S.S. Arizona has lain in the “oily waters of Pearl Harbor” for decades now — a historic relic, a sacred open grave and an environmental dilemma.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese unleashed a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The attack led to the deaths of close to 2,400 Americans, including almost 50 civilians. Of those, almost half died on the U.S.S. Arizona, the ship that, for many, has come to symbolize the entire event.

The forward deck of the Arizona was struck by a 1,760-pound bomb that triggered a massive explosion, lifted the 33,000-ton vessel out of the water and killed 1,177 sailors and Marines instantly. “It wasn’t the bomb itself that created the giant explosion. It was her own ammunition — hundreds of thousands of pounds of ammunition, exploding all at the same time,” Jay Blount, spokesman for the Pearl Harbor National Memorial tells TIME. The ship burned for two and a half days after the initial attack. Blount says that temperatures reached as high as 8000°F — more than three times as hot as lava spurting out of Hawaii’s Kīlauea volcano, which erupted last year.

Before its tragic fate in the Pearl Harbor bombings, the Arizona had been part of the “British Grand Fleet at the end of World War I, [taken] president Hoover on a cruise of the Caribbean in 1931 and [provided] aid after the 1933 Long Beach earthquake,” according to the University of Arizona Libraries Special Collections. The damage at Pearl Harbor was not the first hit that the Arizona had taken. Less than two months before the attack, during a training exercise, the ship was struck on the port side by the U.S.S. Oklahoma, creating a “V-shaped hole, four feet wide by twelve feet long.” That earlier blow took a few weeks to repair, according to the university, but the damage in 1941 was not possible to recover from.

“Today, Arizona rests where she fell, submerged in about 40 feet of water just off the coast of Ford Island,” the National Park Service says. The ship isn’t all that remains underwater. More than 900 sailors and Marines could not be recovered, either. “The overwhelming majority of those men were cremated” in the blast, Blount explains. For Blount, a former Army officer who has worked at American military cemeteries in Italy and France, the memorial represents one thing: a cemetery — “a solemn resting place.”

In 1958, former President Dwight Eisenhower approved a law that would allow the Pacific War Memorial Commission to raise money that would go towards constructing a memorial honor that loss. The commission was tasked with raising $500,000. Fundraising efforts received a significant boost from musical icon Elvis Presley, who helped raise more than $64,000 after organizing a benefit concert in 1961.

The memorial — a white arched concrete structure for onlookers to pay their respects — was unveiled in 1962 and is located above the wreckage. It draws in about 1.8 million visitors a year, according to Blount. There, the names of the 1,177 men who died on the Arizona are inscribed on a white marble wall.

‘A city gone to sea’

Not every part of the Arizona lies at the bottom of the harbor. In 1944, a man named Wilber Bowers, a graduate of Arizona University, found one of the ship’s bells wasting away in a shipyard, waiting to be melted down. He sent the bell to the University of Arizona in 1946, where it remains till this day in a tower especially created for it.

But the majority of the ship is seen today only by those who dive to see it. Divers do not go inside the ship out of respect for the fallen sailors and marines but are able to see what’s on the inside of the ship through a remotely operated vehicle.

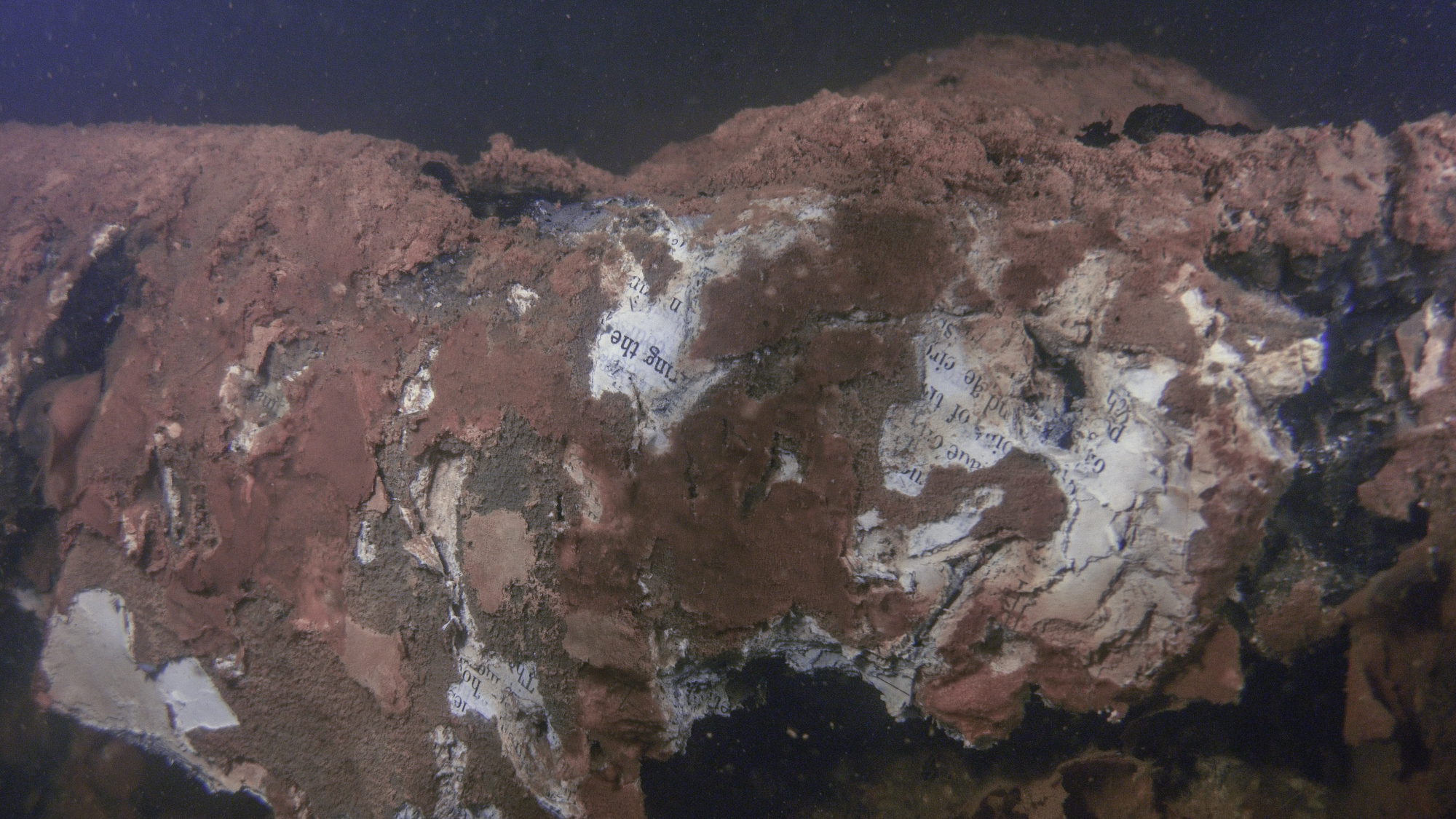

Reminders of the men who lived aboard the Arizona are scattered across the underwater wreckage: a uniform on a hanger, shaving kits, cooking pots, shoe soles. “This was a city gone to sea,” Brett Seymour, a researcher and underwater photographer at the National Park Service, tells TIME. What strikes him as the most poignant observation is a fire hose, coiled in its ready position, just at the edge of where the massive fire raged. “It’s not spread out over the deck like someone grabbed it and fought the fires,” Seymour says. “It’s still coiled as though no one even had a chance to grab it. The blast was so great there was not even a prayer of fighting the fire.”

Seymour, who says he has taken more than 450 dives around the U.S.S. Arizona since 1998, explains it “never feels like just another dive” and that he tries to use photographs to “tell this story further” and keep the memory alive for future generations. “It’s always an honor,” he says.

Edward Linenthal, a history professor at Indiana University who has studied the U.S.S. Arizona, recalls seeing the fire hose too, during a dive he took after a ceremony honoring Pearl Harbor’s 50th anniversary. The Arizona “was kind of like — all good relics are like this — a wormhole to the past,” he says. Some of the artifacts there are “so powerful that it makes it hard to tell dispassionate history anywhere near the place,” he adds. Linenthal says the vessel is in the same category of American historic relics as the Declaration of Independence and Abraham Lincoln’s bloody pillow. But it’s not just a relic, he notes: “It’s still an open grave.”

Linenthal notes in his book Sacred Ground: Americans and Their Battlefields that in 1983 the U.S. Navy and National Park Services heard from a man who claimed he had invented a machine that would “get the bodies out without anyone getting hurt.” The regional director of the NPS responded that “any attempts to remove the remains of these men and disturb their final resting place would be considered by many, including their families, to be a sacrilege.” The Navy “respectfully declined” the offer.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

‘Black tears of the Arizona‘

While the Navy determined in the past that it was best to leave the Arizona at solemn rest, what happens to the wreckage in the future is less clear.

The ship once held about 1.5 million gallons of “Bunker-C” oil and the NPS estimates that 500,000 gallons remain within its hull. The Arizona continues to leak close to a gallon of oil every day.

The oil that remains in the ship is not stored in one big tank but in more than 200 different compartments, according to Seymour. “It could be possible, from an engineering standpoint, to remove the oil but it would require the total destruction of the ship,” he says.

Blount explains that it’s not as simple as taking a hose and draining out the oil because emptying the ship of water and oil would likely result in removing the remains of the crew. “It’s a difficult situation,” he says. But he notes that the park service does communicate with the Coast Guard and the surrounding water is frequently monitored by NPS staff should any significant leakage occur. For now, the fuel that rises to the surface comes up “drop-by-drop” rather than as a steady leak. Bubbles with a “rainbow-looking sheen” often appear for a few seconds before the fuel evaporates.

Some survivors of the attack on the vessel refer to the oil making its way up to the surface as the “black tears of the Arizona.” Folklore suggests that “the ship will continue to cry these black tears until the last remaining survivor passes away,” Blount says.

Even without the oil, the Arizona, if left alone, would not be there forever. The wreckage is currently in sound structural condition, thanks in part to the way the ocean and its inhabitants have adapted to its presence. A process called concretion, in which natural microorganisms grow on surfaces submerged in the water, does not stop corrosion but slows it down significantly, Dana Medlin, a professor at LeTourneau University studying how the ship’s corrosion and structural integrity may impact oil release in the future, tells TIME. But every steel structure in the ocean will eventually reach a point where it corrodes and collapses, he says. Researchers who have been studying how to preserve, manage and monitor the ship for more than a decade, as part of the U.S.S. Arizona Preservation Project, note the ship is already corroding but they do not know yet when exactly it may collapse. “But we do know it’s not anytime soon,” Medlin says. Initial data appears to show that for “we have more than 50 years” before any significant action is needed, he explains.

The Arizona is not the only sunken shipwreck that still has oil on board. Medlin and his colleagues note in a 2011 article that “more than 8,500 potentially polluting shipwrecks containing perhaps as much as 20 million tons of oil have been identified.” Of these, more than 6,000 were lost during World War II.

In December 2016, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzō Abe became the first Japanese Prime Minister to visit the site since it was attacked decades ago. “We must never repeat the horrors of war,” Abe had told reporters in Japan before arriving in America to visit the site with then-President Barack Obama. “I want to express that determination as we look to the future, and at the same time send a message about the value of U.S.-Japanese reconciliation,” Abe had said. The two leaders paying homage together symbolized a powerful gesture of peace for many. “To see the two nations that were bitter enemies in 1941 through 1945 together at the place where all of that bloodletting began was very powerful,” Blount says. “It really speaks to people’s ability to reconcile.”

Servicemembers who were assigned to the Arizona the day it was attacked by the Japanese can choose to have their remains left in the sunken ship. So far, 43 have already opted to do so, Blount says. Today, only three survivors of the attack who were onboard the U.S.S. Arizona are still alive and they have all indicated that they want to be buried in a family cemetery, according to Blount. But Lauren Bruner, a survivor of the attack on the vessel who died in September, chose to have his ashes interred on the wreckage.

That ceremony is set to take place on Saturday, the anniversary of the attack — and will likely be the last time a crew member’s remains are stored on the battleship, laid to rest with his fellow shipmates, on the bottom of the harbor.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com