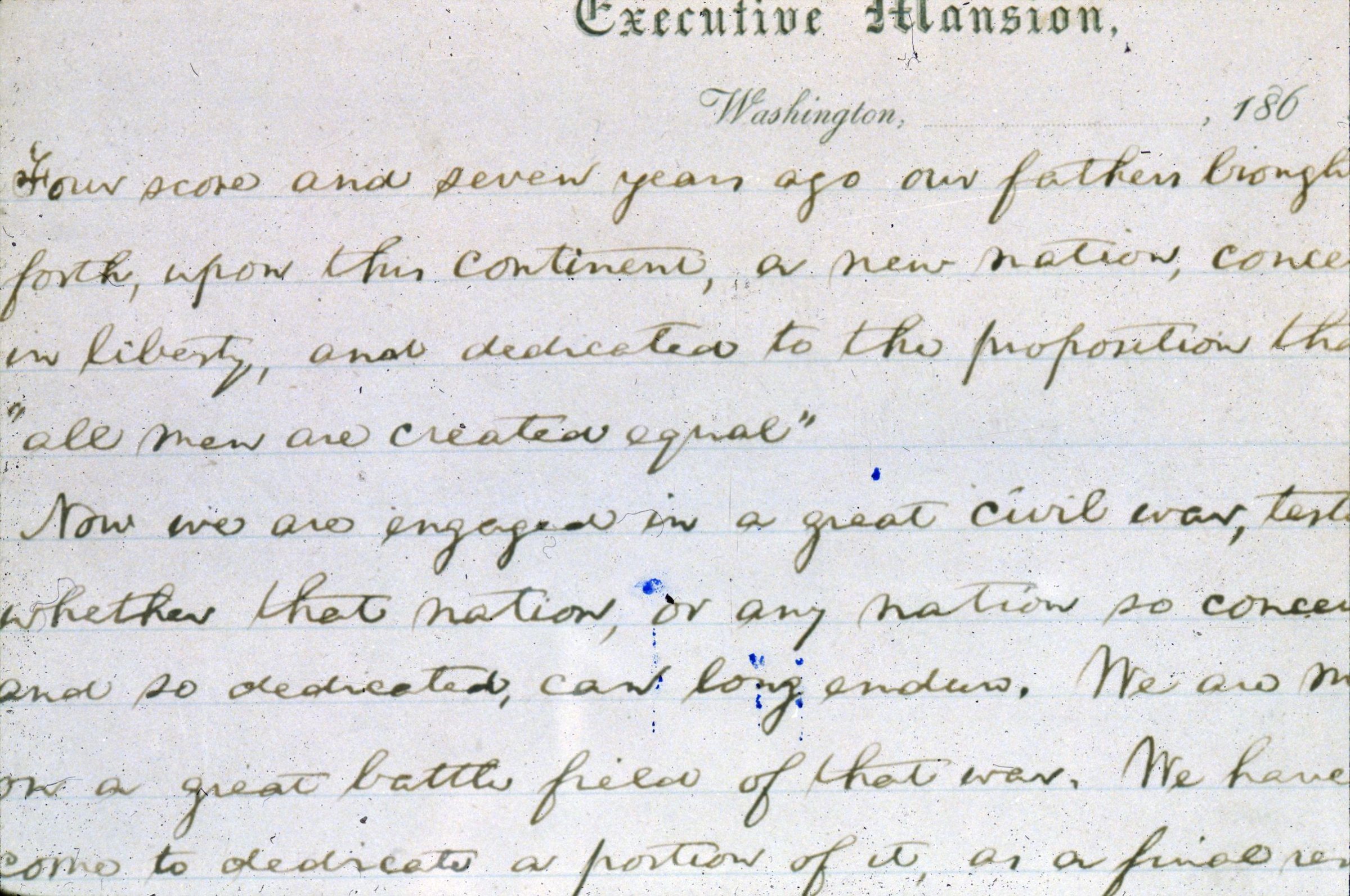

On Nov. 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln spoke at the dedication of the battlefield cemetery at Gettysburg, Pa. For the smoothness of its music, the gravity of its occasion and the conciseness of its 272 words, the Gettysburg Address occupies a unique position in American oratory.

What more is there to say about America’s most famous speech? Maybe this: that it was not meant to be unique. The style was Lincoln’s, with a little help from the King James Bible (“fourscore and seven years ago” echoes Psalm 90:10). But the intellectual power of the Gettysburg Address is deliberately borrowed from America’s founding documents. And yet, although America was “conceived in liberty” with the Declaration of Independence was written and signed — four score and seven years back from 1863 equals 1776 — and its “government of the people, by the people” comes from the Constitution, the pursuit of liberty with which Lincoln engaged is much older than either. What was old news for Lincoln and his audience during the Civil War had already been old news even in the first days of independence.

Americans began striving for liberty before the United States was a country. The freedom to write critically about the government had been won as early as 1735 in the trial of John Peter Zenger, a New York newspaperman. Zenger’s paper, the Weekly Journal, had waged a year-long campaign against the royal governor of the colony, arraigning him for high-handedness and mocking him and his supporters as spaniels and monkeys. The governor responded by hauling Zenger into court. British law criminalized criticism of rulers on the grounds that it might foment rebellion. But Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, persuaded the jury to ignore the law, on the grounds that men had a natural right “both of exposing and opposing arbitrary power.” Zenger’s acquittal—essentially an act of jury nullification—left the press in colonial America the freest in the world.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The American struggle for religious liberty began even earlier. Peter Stuyvesant, the one-legged governor of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, was a bigoted Calvinist, determined to cleanse his domain of Quakers, a new countercultural sect that ignored social rank and let men and women preach equally. But in 1657, 30 of Stuyvesant’s subjects in the Long Island village of Flushing sent him a defiant letter in which they insisted on doing “unto all men as we desire all men should doe unto us, which is the true law both of Church and State.” The Flushing Remonstrance laid down a marker of individual conscience. (Literally: six of the signers could not spell their own names, but only made marks.) Stuyvesant’s bosses in Holland told him to leave Quakers alone—a milestone in American liberty, as New Netherland was absorbed into British North America in 1664.

And even older than that is the power of the people, which went back to the first British colony. Jamestown, founded in 1607, struggled with war, drought and starvation. In 1619 it began an experiment with a new model of government—a General Assembly consisting of the governor and his advisors, appointed in London, and 22 burgesses, two each from every settlement in the colony. Burgesses were elected by a “pluratie of voices” in their constituencies—one man, one vote. The Assembly made decisions the same way—governor, advisors and burgesses casting one vote each (the governor did wield a veto). Over five summer days the Assembly’s first session set tobacco prices, outlawed drunkenness and whoredom, and discussed Indian relations. Economics, morals, foreign policy—the stuff of politics ever since.

Jamestown is also infamous for something that happened only weeks after the Assembly adjourned: the purchase, off a privateer ship called The White Lion, of “twenty and odd Negroes,” who would be British America’s first slaves. Though the pursuit of liberty has been part of American history for centuries, the denial of that very ideal has been part of the story for just as long—and Lincoln was mindful of that history too. In his Second Inaugural Address, in March of 1865, he spoke of slavery’s “two hundred fifty years of unrequited toil.” (1865 minus 250 equals 1615: close enough.)

The carnage of the Civil War, he believed, was divine punishment for that primal sin. But Lincoln had won office and rallied Americans to save government of the people, through politics—the very process begun at Jamestown. Self-rule was Lincoln’s Jamestown project.

Lincoln was not offering a birth of new freedom; what he wanted was “a new birth of freedom,” the freedom we had long pursued. We do best when we keep it, as he did, in our heads and our hearts.

Richard Brookhiser is senior editor of National Review and a columnist for American History. His most recent book, Give Me Liberty: A History of America’s Exceptional Idea, is just out from Basic Books.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com