“There have always been dazzling Windsors, and dull ones,” says Prince Philip matter-of-factly to Queen Elizabeth II (Olivia Colman) in Season 3 of the Netflix series The Crown. Yet the “dazzling” Windsor to whom Philip is referring isn’t his wife, but her sister, Princess Margaret.

In seasons 1 and 2 of the hit show, the storyline involving Margaret — whom TIME once dubbed “a Royal Lightning Rod” — detailed her rebellious streak, setting the scene for her unconventional marriage to photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones, known by the time Season 3 begins as Lord Snowdon. This season of the big-budget show, in which Helena Bonham Carter takes over the role from Vanessa Kirby, covers the turbulent years in the princess’ life beginning in 1964, after her wedding to Armstrong-Jones, up until one year before the couple’s divorce in 1978.

Here’s a look at how Margaret’s storyline in The Crown Season 3 stacks up against real-life events.

What happened when Margaret traveled to the U.S. in 1965?

Episode 2, Season 3 of The Crown opens with a flashback to 1943 at Windsor, when a young and confident Margaret says that she wishes to be queen instead of her hesitant sister. Titled Margaretology, this episode then flashes forward to depict Margaret’s first visit to the U.S., in 1965. The visit, which did take place in real life, came at a tense moment for Anglo-American relations. As depicted in The Crown, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson (played by Jason Watkins) was elected in 1964, and his relationship with U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson was more distant than the “special relationship” had traditionally been in the past. Some historians have argued that this was due to Wilson’s reluctance to commit British troops to the war in Vietnam, a point suggested in The Crown when Johnson remarks, “If Harold Wilson wants my help, he should’ve thought about it before deciding not to support me on Vietnam.”

The “help” here was financial assistance. The economic situation when Wilson took office was dire, with an £800 million deficit on the balance of payments. “There was essentially a financial crisis which required the U.K. going to the International Monetary Fund to get a loan, and the most important aspect was that they needed to get the green light from the U.S. to approve it,” says Matthew Jones, professor of International History at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

So how did the glamorous Princess Margaret factor into all this? The Crown depicts Johnson declining an invite from Elizabeth for a state visit to Buckingham Palace. Indeed, Johnson was the only one of 11 presidents who did not meet with the Queen since the start of her reign, but it’s unclear whether he officially declined any invite. The Crown also seems to have taken some creative license, suggesting that Margaret helped secure the loan by visiting the White House and charming Johnson.

Britain’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs said in early 1966 that Margaret’s November 1965 trip began as a private visit in response to an invitation from a former United States ambassador in London, before developing into a trip consisting of “official and public engagements undertaken at the specific request of Her Majesty’s Government.” In fact, arrangements for the loan had already been discussed in September 1965 two months before Margaret’s trip, where U.S. Undersecretary of State George Ball visited London and negotiated the terms of the loan with Wilson. “The quid pro quo was that the U.K. agreed to maintain a military presence in southeast Asia for the foreseeable future,” says Jones. “The Americans did not want the British to contract out of southeast Asia at the very time they are committing large-scale ground forces to Vietnam, which had been taking place in the summer of 1965.”

Was Margaret’s U.S. trip considered a success?

Margaret and Armstrong-Jones departed for the U.S. for 20 days at the beginning of the month, to an already captivated U.S. public. One local California newspaper said that her trip had triggered “five months’ of plans that leave nothing to chance.” Met by fans at every step of the way, the pair started their travels in San Francisco before heading to Los Angeles, Washington and New York on over 60 official and public engagements, as well as a private visit to Arizona.

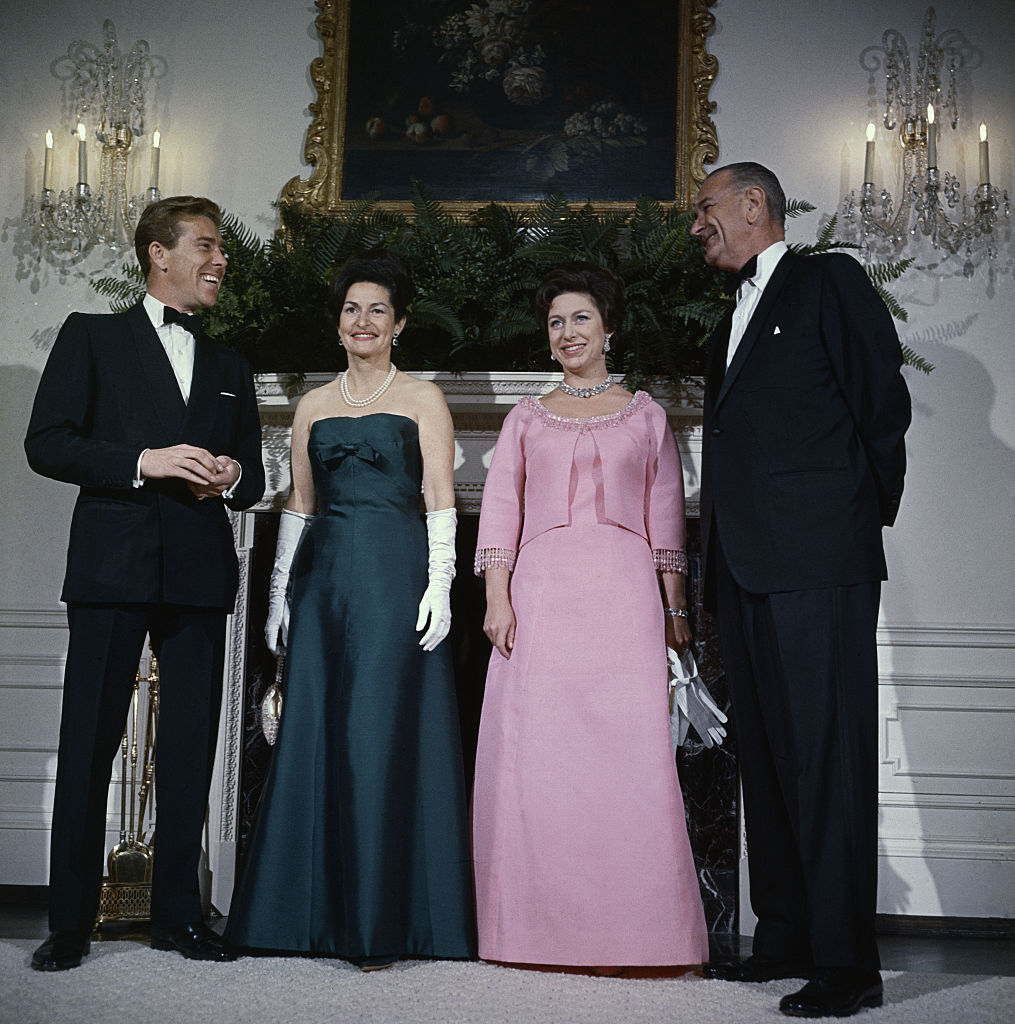

“What we have witnessed in Princess Margaret is a more vibrant, modern and engaging version of her older sister,” reads The Crown‘s Armstrong-Jones, played by Ben Daniels, to Helena Bonham Carter’s Margaret from an American newspaper. In reality, the pair also mingled with stars like Elizabeth Taylor, Judy Garland and Frank Sinatra in Los Angeles, as seen in a PBS documentary on the princess’ American tour earlier this year. (But the princess, as reports go, offended Taylor, Garland and Grace Kelly with her frank comments.) The Johnsons hosted Margaret and Armstrong-Jones at the White House, where the two couples posed together happily for photographs — although we can’t say for sure whether the princess and the president really did perform a duet for their dinner guests as depicted in the show.

And while the British government’s official line was that Margaret’s trip to the U.S. was “an outstanding success” in capturing the American public imagination, observers back in the U.K. were less impressed. Several newspapers commented on Margaret’s flashy exploits, as well as the expense of the trip. Margaret’s behavior was also the subject of a heated debate in the U.K. House of Commons, where one MP pointed to the pricey trip as distasteful in the context of “millions of people in this country who are suffering poverty and hardship, [still] millions without adequate housing accommodation.” Government documents declassified in 2003 also suggested that U.K. diplomats barred Margaret from visiting the U.S. again in the 1970s because of the bad press caused by raucous, partying behavior she and her entourage exhibited during the 1965 trip.

Was there tension between Margaret and Queen Elizabeth II at this time?

The Crown depicts Margaret’s trip to the U.S. as stoking her sister’s insecurities, comparing her own “predictable, dependable, reliable” nature to Margaret’s “instinctive, spontaneous, dazzling” character. Indeed, one of the overarching themes of the season is how different members of the family deal with undertaking their royal duty. “We all have a role to play. Elizabeth’s will be center stage, and yours will be from the wings,” a young Margaret is told sternly in another flashback to the sisters’ childhood.

According to observers, the sisters’ personalities were indeed vastly different, and Margaret reportedly had nightmares about disappointing Elizabeth. According to Reinaldo Herrera, a royal family friend, their closeness “was beyond comparison with the relationship between any other siblings in the world,” with a direct phone line connecting Kensington Palace to Buckingham Palace so the two could speak daily.

“She [Margaret] could just squash a conversation by the correction of a spelling or a pronunciation, but on the other hand, she was one of the nicest, most caring and generous people you could ever wish to meet. She could be and was a lot of fun,” said Christopher Warwick, author of Princess Margaret: A Life of Contrasts, in an interview. “Even the queen regarded her sister, and she’s on record as having said it, that she always regarded Margaret as an enigma, and she was. Margaret was exactly that. She was an enigma.”

Did Margaret struggle with alcohol?

Throughout season 3 of The Crown, Margaret is depicted as being volatile in her moods, and often under the influence of alcohol. In real life, she reportedly liked to glue matchbooks to the side of drinking glasses so that she could light her cigarette without having to put down her drink.

“She was somebody who had a very low boredom threshold, somebody with a very active mind,” Bonham Carter said in a recent interview. “I think that’s why she would medicate with drink. A lot of royal life is incredibly boring.” The actor actually met the real-life inspiration for her character a couple of times, as Margaret was friends with Bonham Carter’s uncle Mark Bonham Carter—the two were rumored to have dated. “She was very far away. There was a huge remoteness about her, which might have been her depression, it might have been her drinking. She was removed,” Bonham Carter said of Margaret during the late 1990s, a few years before she died in 2002.

What was Margaret’s marriage like during this time?

As suggested in Season 2 of The Crown, Armstrong-Jones had affairs prior to his marriage to Margaret. Season 3 explores the breakdown of the couple’s marriage, depicting their disagreements during the U.S. tour as well as their explosive arguments and infidelities on both sides. By the time Season 3 starts, Margaret and Armstrong-Jones have become parents; their son David was born in 1961 and their daughter Sarah in 1964. But both the princess and the photographer are unhappy in the marriage; the final episode of the season shows Armstrong-Jones’ affair with Lucy Lindsay-Hogg, who had worked with him on a documentary film in Australia and would later become his second wife. As depicted in the show, the lovers would often escape London to stay at Armstrong-Jones’ childhood holiday home of Old House, in Sussex, a residence Margaret despised.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Armstrong-Jones would busy himself with his photography projects, often separating from Margaret for long periods. “Rumors abounded of Snowdon’s dalliance with fashion models,” reported TIME on the news of the couple’s divorce in 1978. Anne de Courcy, author of Snowdon: The Biography, writes that the couple’s arguments were marked by his put-downs and dismissive jokes of her in public, as well as her possessiveness and jealousy over his affairs. Armstrong-Jones would reportedly speak over Margaret at dinner parties, telling her to “shut up and let someone intelligent talk.” The Crown also shows Margaret opening a book and finding a note inside from Armstrong-Jones that read, “You look like a cheap pantomime dame.” Apparently such notes of “things I hate about you” were commonplace, and Armstrong-Jones would leave them around the house for Margaret to find. A well-reported example was found in Margaret’s glove drawer, reading: “You look like a Jewish manicurist.”

Did Margaret have an affair with Roddy Llewellyn?

The Crown depicts then 43-year-old Margaret meeting 26-year-old Roddy Llewellyn at a party hosted by Margaret’s close friend Lady Anne Glenconner at her country estate in Scotland. The encounter really did happen that way in 1973; Lady Anne said in a recent interview that Llewellyn was invited to make up the numbers at the party. “We had introduced them, though he wasn’t meant for her,” Glenconner said. “Tony [Armstrong-Jones] was behaving appallingly, with all his mistresses, and being not at all kind to her. He was spiteful in creative ways.”

In reality, Margaret did embark on a long-term affair with the aristocratic gardener Llewellyn, who was 17 years her junior. The affair was very public, playing out in the tabloids amid the breakdown of Margaret’s marriage to Armstrong-Jones. In 1976, Llewellyn traveled with Margaret to her holiday residence, which rather ironically had been gifted to her as a wedding present, on the Caribbean island of Mustique. As shown in The Crown, a tabloid photographer followed the lovers to Mustique and captured Margaret and Llewellyn in their swimsuits on the beach, causing a scandal back home.

“Feminism was growing but still there was a double standard that for an older woman being with a younger man at that time was a huge thing, and much more than it would be today,” said Chris Granlund, executive producer of the documentary Margaret: A Rebel Princess, in an interview. “He was constantly referred to as her ‘Toy Boy.’ Politicians called him that when they were attacking the royal family in parliament. So [their relationship] was used as a weapon against the royal family.”

Margaret and Armstrong-Jones formally announced their divorce in May 1978, after 18 years of marriage. As TIME reported, and as The Crown depicts, it was the first divorce in Britain’s immediate royal family since Henry VIII dissolved his marriage to Anne of Cleves over 400 years earlier in 1540. Armstrong-Jones married, to Lindsay-Hogg, in December 1978, while Margaret and Llewellyn’s affair eventually fizzled out. “I didn’t think about the consequences of such a high-profile affair,” Llewellyn said in a 2002 interview. “If we all had crystal balls, we’d all know which horse to back, wouldn’t we? I was just following my heart.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com