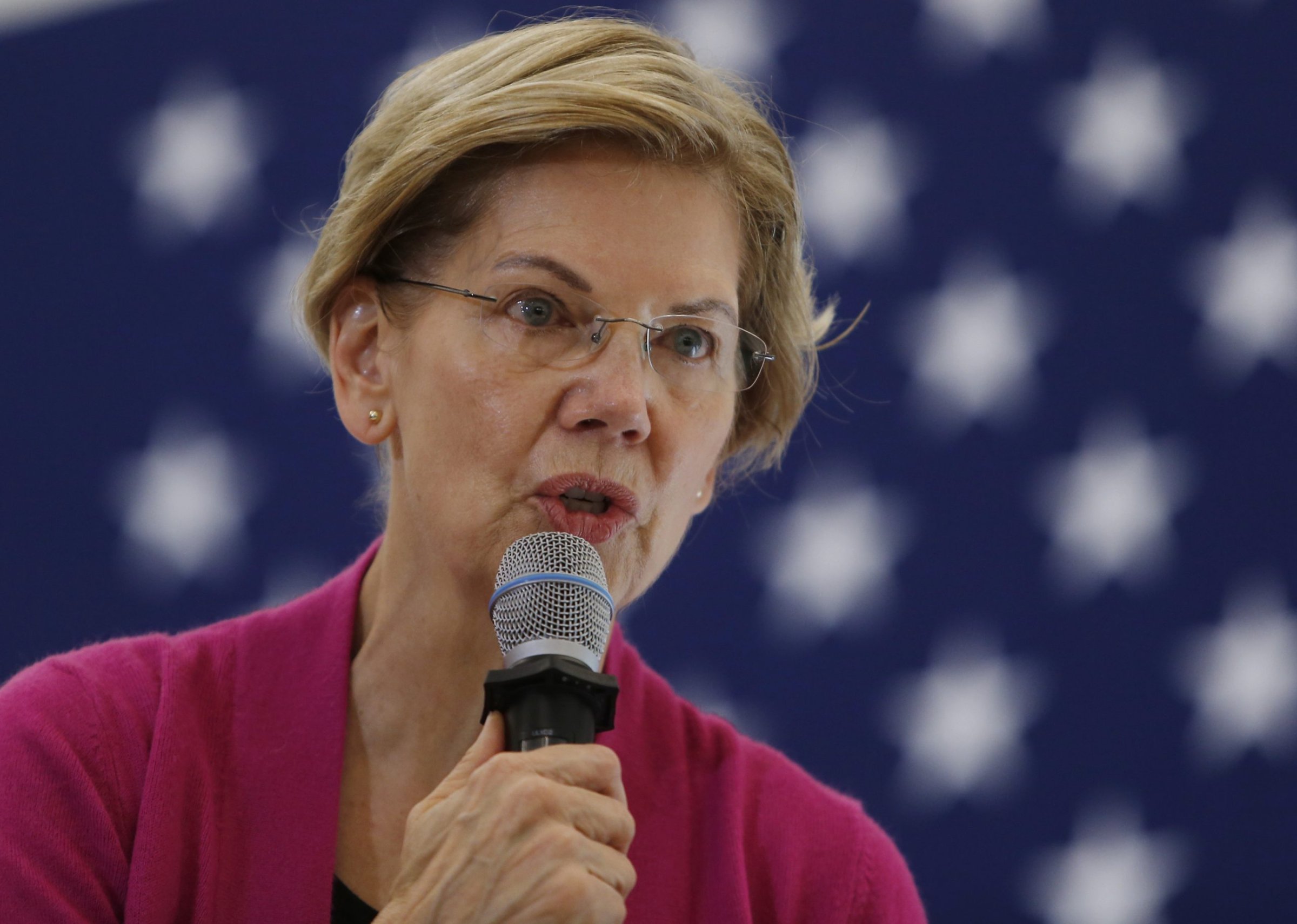

Elizabeth Warren has built her top-polling presidential campaign on her reputation as a liberal fighter and iconoclast willing to take on the biggest inequities besetting the middle class. That rhetoric has, at times, made her virtually indistinguishable from her friend and rival in the Democratic field, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.

But as a policy wonk and politician, Warren has often been much more of a pragmatist than Sanders. As the architect of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau and, later, as a Senator from Massachusetts, she regularly sought compromise, worked within institutional strictures, and embraced incremental improvements to pass small-bore legislation, rather than holding out for wholesale reform.

Warren’s detailed proposal, which was published on Medium on Friday and describes how she would pay for Medicare For All, is a reflection of that divide.

While Warren’s plan embraces the relatively radical idea of Medicare for All—universal, government-funded health care for all Americans—it is hardly a breathless document. Throughout the roughly 9,000-word post, Warren repeatedly reminds supporters of the complexity of actually accomplishing the goal legislatively. She describes Medicare for All as a “long-term goal” four times and reminds readers that it likely won’t happen in a single term: “it is possible to eventually move to a Medicare for All system,” the document says.

“Of course, moving to this kind of system will not be easy and will not happen overnight,” Warren’s plan reads. “This is why every serious proposal for Medicare for All contemplates a significant transition period.”

The plan says it would cost $20.5 trillion in new government spending over a decade, a price tag that Warren says she would pay for with new taxes on corporations and the wealthy, but not the middle class. It describes in relatively minute detail, complete with links, how the federal government would curb the cost of health care by reducing administrative costs and reforming payment, and increasing competition among hospitals.

Sanders, in contrast, recently told CNBC he does not plan to release a definitive plan of how he’d pay for Medicare for All. His Medicare for All bill does not include details on financing. In April, his campaign released a short list of options for funding the health care program, although none would cover the full cost. At Sanders’s rally in Queens last month, several of the speakers sidestepped details, describing him instead as the “only one” who could champion the progressive policies he represents.

Warren said Friday that she will disclose more information about her Medicare for All transition plan in the coming weeks. It will, she said, address concerns raised by unions, hospitals, and medical professionals, as well as those who currently have private insurance or work for private insurance companies. Those groups have all raised concerns about all Medicare For All plans, including Warren’s, that call for eventually eliminating private insurance.

Moderate Democratic candidates, including Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar and South Bend, Ind. Mayor Pete Buttigieg, have seized on those groups’ concerns. Some have embraced more incremental plans that would offer voters the option of buying into a Medicare-like program, while keeping the private insurance industry intact.

Much of the reaction to Warren’s proposal on Friday centered around the fact it was, at last, an answer to the oft-asked question of whether her Medicare for All plan would raise taxes on the middle class. The question has come up repeatedly at Democratic debates, but she has avoided answering it. As Warren has risen in the polls, her Democratic rivals have increasingly needled her for failing to do so. “Your signature, Senator, is to have a plan for everything—except this,” Buttigieg said at the last debate. Supporters applauded Warren’s proposal as a “win for the Medicare for All movement.”

Voters, meanwhile, are now armed with another detail to help them differentiate a crowded Democratic field. Whether Warren’s commitment to pragmatism and policies can win over those who love the big ideas will still be an important test for her campaign.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com