This post is in partnership with History Today. The article below was originally published at History Today.

The Aliens Act of 1905 was the first attempt by the British Parliament to establish a system of controlled migration. As such it is seen by historians as a watershed moment, putting an end to the Victorian “golden age” of migration, which, with its ever-decreasing transport costs and growing demand for labor, saw the movement of people reach unprecedented levels. The Act ushered in a new era of increasing border controls, seen as the main way to regulate whoever could enter the country.

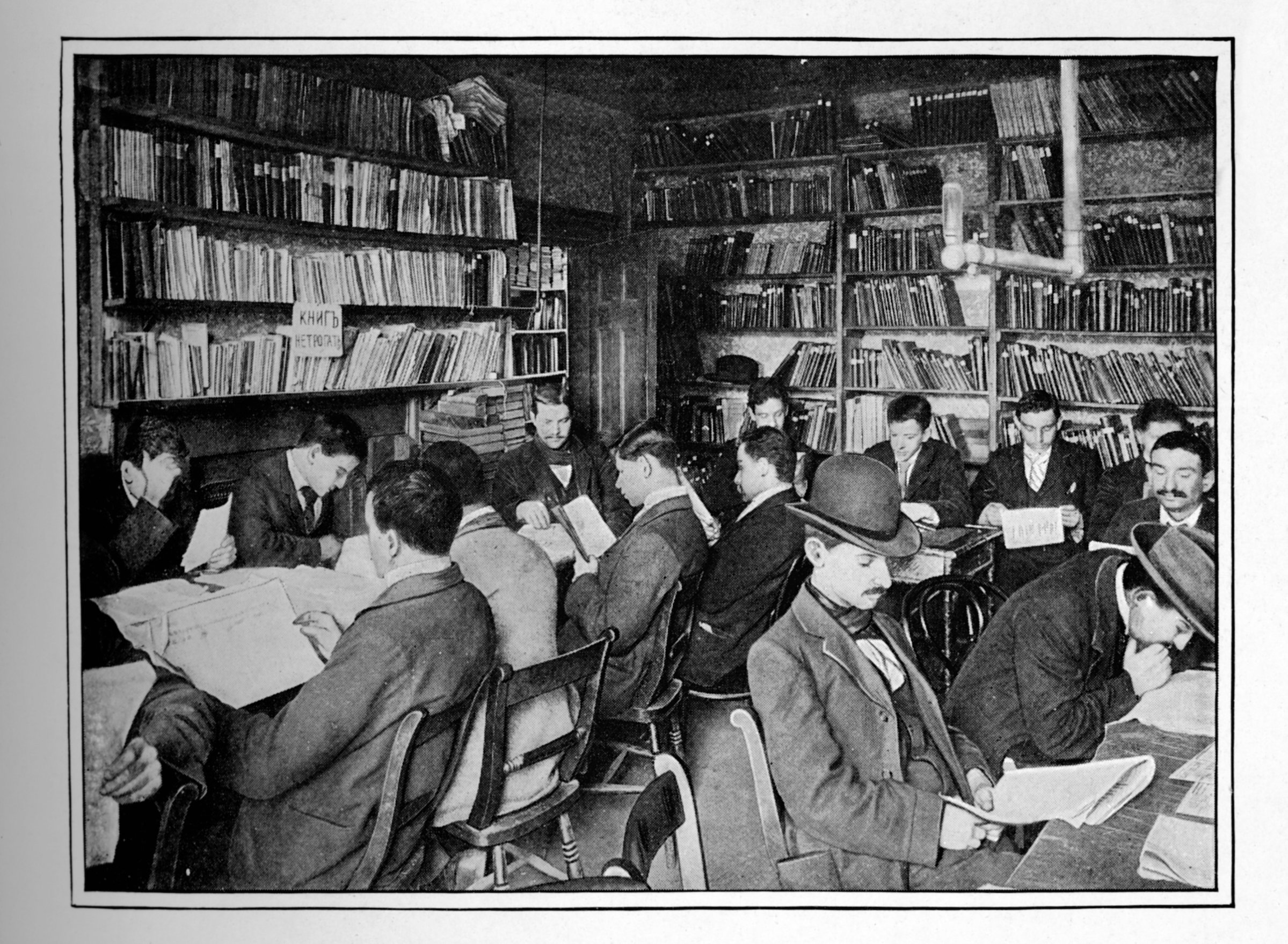

Concern over migrants was nothing new for British society. Initially, there were the Irish, who, fleeing the Potato Famine of the 1840s, settled in large numbers in the U.K. where they joined the ranks of the workers of the fledgling Industrial Revolution. Although a great many of them settled only temporarily in Britain, a large number remained. Albeit technically already a part of the U.K., their presence in England, Scotland and Wales constituted a crisis for British society. They were subjected to racial abuse, vilified in official reports, required special relief payments from the government and their presence created tensions within the labor market. A few decades later, towards the tail end of the century, the story was repeated for migrants from the Continent. There was public outcry that German clerks accepted lower wages than their local counterparts, for example, while Italian ice-cream vendors were accused of preparing their products in unhygienic conditions: the London Evening Standard warned in 1892, contrary to the official sanitation inspectors, that “Italian ice-cream makers we have always with us nowadays, and from their abiding place too commonly fever proceeds.” Eventually, public attention focused on the so-called “Polish Jew” — Jewish people from the western side of the Russian empire, which, at that time, included Poland. In this area, known as the “pale of settlement,” Jews were allowed to live on a permanent basis. From the 1880s onward, prompted by terrible antisemitic persecutions, the Pogroms, many fled. Around 150,000 settled in the U.K.

Anti-immigration sentiment became organized at the turn of the century, driven chiefly by the British Brothers’ League, founded in 1901, and Major William Evans-Gordon, who became Conservative MP for Stepney in 1900 on a strong anti-immigration platform. Warnings were issued that, if immigration was not stopped, England would soon witness “summary measures of similar aim with those adopted by the Russian Government” — ethnicity-based persecution and decimation. Not just strongly antisemitic, their rhetoric focused on the idea of a “foreign invasion” of destitute aliens who worsened the living conditions in the inner city slums. One anti-migration essay stated: “Uneducated and slovenly when they come, they never improve, and despite all efforts to restrain them, they persist in following here the same mode of living which they practiced at home” and “The emigration lists are swollen with the names of Englishmen prevented from making a worthy living in their own land.” Although none of the official reports found any links between a foreign presence and lower wages, this idea gained momentum.

But what constituted an immigrant? The Union of the Crowns under James Stuart (VI of Scotland, I of England) prompted the question of the Scots’ relationship to the English legal system. This was answered in Common Law in “Calvin’s Case” of 1608, which stated that the only meaningful requirement was being born into allegiance to the king. The so-called Ius Soli, the law of the land, meant that all British-born descendants of immigrants, and everybody born in overseas territories directly controlled by the crown, were considered British citizens.

It is on this basis that the Alien Act was passed in 1905. Its most important provisions were that “leave to land” would be refused to those migrants who could not support themselves or were likely to become a charge on the state for health reasons. Naturally, in order to screen the migrants in such a way, the Act also provided that they could only disembark in approved ports where an Immigration Officer, a new position created as a direct consequence of the Act, would inspect them together with a health official. Refused immigrants could appeal to the Immigration Board. This established, for the first time in the U.K., an administrative machine for the control of migration, with all its members appointed and instructed by the Home Secretary. The Act also created criminal offenses for both immigrants and the captains of the ships which transported them. The strong discretionary powers enjoyed by successive British governments in matters of migration were present from the start.

Although this might appear to be an efficient system for the control of immigration, in practice it was limited in its effects, because it only applied to ships which carried more than 20 “aliens” in third class accommodation. First and second class passengers were exempt from any form of control. Moreover, political and religious refugees were explicitly exempt from these provisions and their right to asylum recognized in legislation.

The Conservative government that passed the Act was soon ousted by a new Liberal administration. The discretionary powers transferred to the new Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, who used them explicitly to instruct the members of the Immigration Board that immigrants should be given the “benefit of the doubt” where there was disputed evidence over their refugee status. From 1906 the press was allowed to attend board meetings and in 1910 immigrants were permitted legal assistance. The refusal rate under the new act was relatively low (the highest figure is 6.5% in 1909) although there are indications that some groups, such as gypsies, were disproportionally affected by it. Moreover, there are many indications of widespread irregularities and officials were often openly hostile to immigrants: considerations which fell outside the scope of the Act were often aired during the board meetings, whether they be job concerns, employers being asked if they could find an Englishman to do the work that the migrant had been called to do, or moral considerations; and unaccompanied young women were regularly detained.

The act was in place for eight years before being eventually subsumed into the Alien Restriction Act of 1914 when the start of the Great War led to new, more stringent, border controls.

Marc Di Tommasi is a teaching fellow at the University of Edinburgh and researches the history of migration.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com