The Tony Award-winning playwright David Henry Hwang has a conflicted relationship with The King and I: enamored by its music, troubled by its exoticization and yellowface past. Soft Power, his newest musical running through Nov. 17 at New York City’s Public Theater, is his attempt to confront the musical’s contradictions and bring it into a new era. With music by fellow Tony winner Jeanine Tesori, Soft Power emulates the musical grandeur of The King and I, but also flips its racial politics on their head by depicting a Chinese man who comes to America and falls in love with a white woman—namely, Hillary Clinton.

This conceit might be strange enough, but Hwang uses the musical to wander into even more prickly territory: he dramatizes his own stabbing in 2015, which nearly killed him; explores gun violence and white nationalism; and meditates on Asian-American identity during an era of escalating tensions with China.

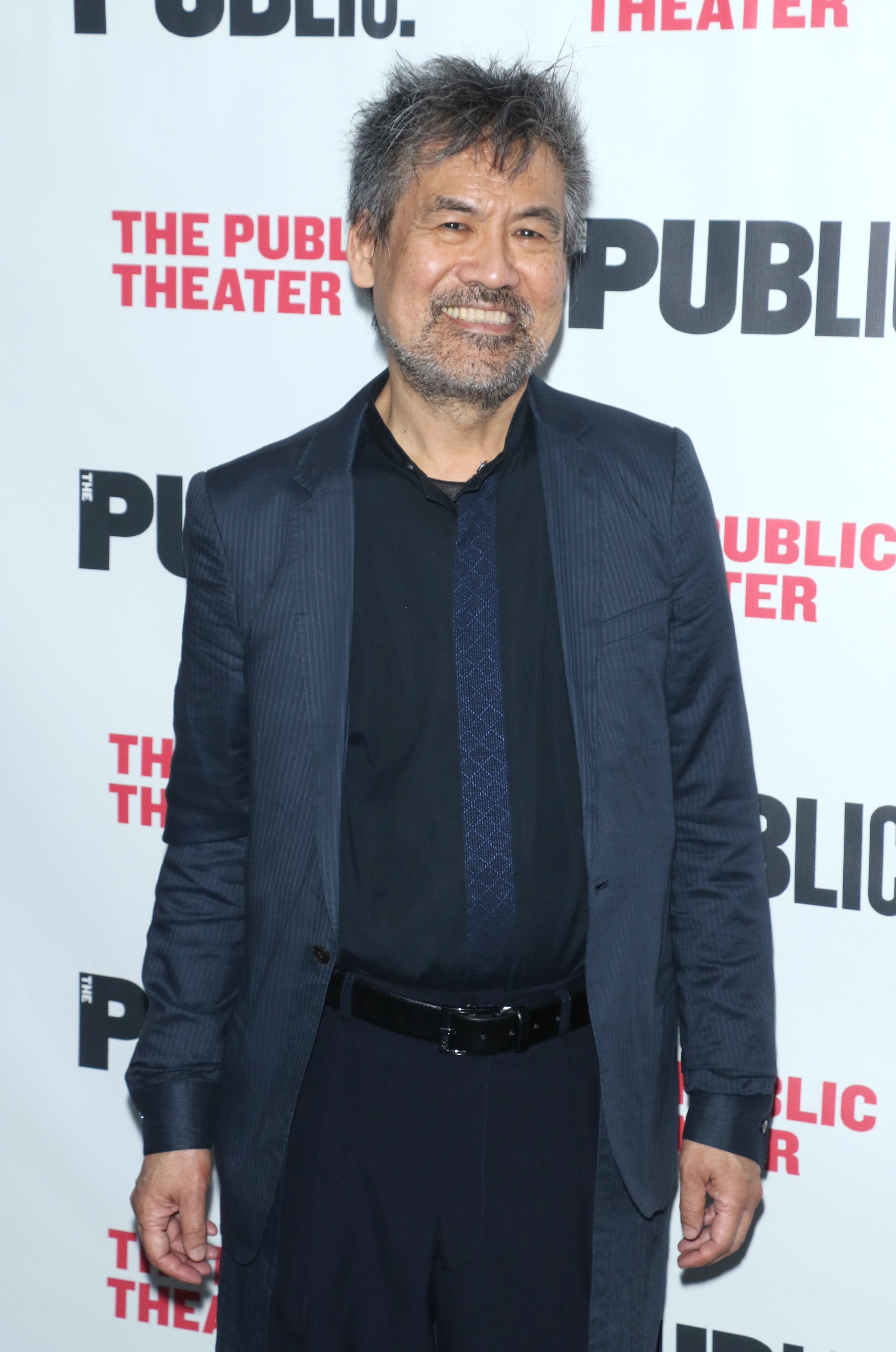

It’s a lot to chew on, but if there’s anyone who can pull off such an ambitious amalgam it’s Hwang, who has dealt with identity issues and East-West tensions in plays like Yellow Face and M. Butterfly—both of which made him a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. In an interview at the Public, Hwang talked about internalized oppression, the tricky balancing act of reviving classic musicals and what he learned from Sam Shepard. Our conversation, below, has been edited for clarity.

Your plays Soft Power and M. Butterfly are extensions of The King and I and Madame Butterfly, respectively. What interests you about creating work in dialogue with classics?

Of course, there’s a tradition of this: think of Greek myths, Shakespeare, or Chinese opera. But when I was an Asian kid in America in the ’60s, and whenever there was any TV show or movie with an Asian character, I would go out of my way not to watch it because I just assumed it was horrible. I’ve come to realize, maybe from working on this show, that as a kid I felt oppressed by American popular culture. Therefore, a lot of my adult life has been about trying to gain access to the levers of that culture.

Do you still feel like American pop culture is oppressive?

I think American pop culture is still pretty oppressive. Hollywood has begun to realize that diversity is more than just a suggestion—it’s really economics. As the writer Jeff Yang puts it, racism is no longer a viable business model. That potentially means that things are getting better. But it’s not hard to find examples of American pop culture now that recycle tropes that are racist and sexist.

You were almost killed from being stabbed in New York in 2015. Has it been difficult to regain a basic trust in the world?

Not so much. I think I repressed the whole thing sufficiently that I was able to just go about my business. But that anxiety has to go someplace—and it went into this play.

Soft Power explores the differences between the Chinese approach to creating art and the American approach. Do you believe the two are fundamentally different?

They are and they aren’t. People who are making art in China are subject to content restrictions. But one could argue that in the West, you’re also working under content restrictions—they’re just capitalist. However, I think there is probably an inherent contradiction between China’s desire for soft power and its top-down control of artists. I think it’s a problem—and one of the reasons why they’ve never been successful in creating an international hit musical.

Conversely, what can Americans learn from the Chinese perspective?

In terms of civil society, China’s lack of freedom is a problem. But the more kind of communal understanding and care for one another—that feels like something America, in its hyper-individualism and runaway capitalism, could learn from.

Do you think classic plays with problematic origins and elements, like the King and I or Porgy and Bess, should be retired?

I don’t advocate the retirement of plays. I feel like there are wonderful things, craft-wise, about a lot of these works. It’s important to see them through kind of a dual lens—to both understand the value of the craft and be able to understand how the delivery system was flawed. I think it’s quite possible some of these works will be retired as they outlive their usefulness. But in the meantime, it’s fine to be aware of what we’re seeing—and be rigorous about understanding the context in which they were made.

How have the increased geopolitical tensions between China and the United States complicated your identity as an Asian American?

It reminds me more of when I was a kid. I never experienced overt racism, but you always knew that you were not completely accepted. And at that point, the United States had been at war with practically every Asian country. So having this face means that you kind of look like the enemy, in history or in current events or in movies.

I think the way that America has treated Asian Americans has always been a function of America’s relationship with the Asian countries it was in conflict with. There were trade tensions with Japan in the ’80s, when Vincent Chin was killed. [Chin was a Chinese-American man beaten to death by two white autoworkers who were angry about the rise of the Japanese automotive industry.] Then there was a period in the ’90s and aughts where for a while, China becomes kind of cool and powerful. And now, the tensions with China, which hopefully don’t turn in a war, have kind of brought about a reversion.

Early in your career you were often the only Asian American in the room. Now, a new wave of Asian-American artists, from Awkwafina to Young Jean Lee to Mitski, has come to the fore amidst a larger dialogue about Asian representation. Has this increase in visibility changed your artistic mission?

I think it’s nice that I don’t have to be the loner. There were advantages of being out there when there’s nobody else and getting to be the visible writer. But the burden you carry is impossible to fill. Because if there’s only one Asian-American novel, for instance, it has to represent the entire community. There’s no way any book can do that.

So the answer is a diversity of works that have a range of points of view. The diversity means I can write the thing that I want to write, which is reflective of me—that also might be reflective of the experiences of others that have this face.

You studied playwriting with Sam Shepard. What’s the most enduring thing you learned from him?

He was really rigorous about work that feels honest, as opposed to something that feels contrived for effect. I certainly write things that are contrived for effect—in this show I manipulate musical theater tropes or white savior tropes. But I think the root of Soft Power comes from a very personal and honest investigation of what it means to be Asian American, and therefore, what my relationship is to China.

You’re writing the live-action adaptation of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Did you ever think you would be writing a major Disney movie?

No. Because I studied with Sam and started writing in the late ’70s, I never expected my work to go on Broadway—because I thought, “Oh, that’s commercial crap.” The fact that I was able to have as varied a career as I have, has been amazing. And it really helps to be in touch with my 16-year-old self. If he were to see what I’m doing today, he would say, “Wow, that’s really great!”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com