After the biggest earthquake to hit Southern California in 20 years struck in July, a powerful fault line that could cause a magnitude 8 earthquake began moving, scientists say.

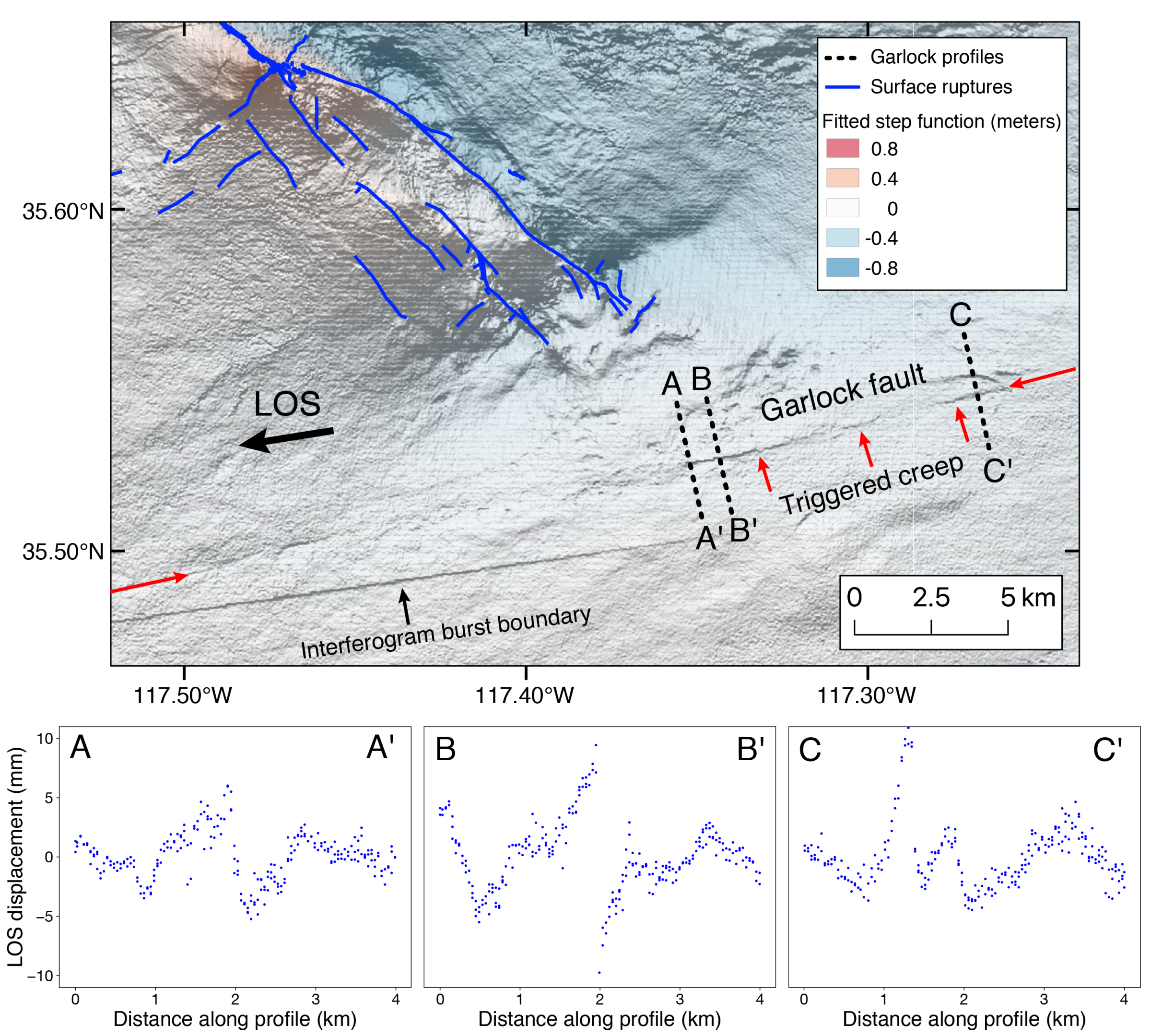

In a study published Thursday in the journal Science, researchers from the California Institute of Technology along with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory said a part of the Garlock fault slipped after being triggered by the series of earthquakes in the Ridgecrest area. The fault runs 185 miles east to west from the San Andreas Fault to Death Valley. Scientists found that it has slipped 0.8 inch (or about 2 centimeters) near its surface since July.

Researchers were able to record the movement for the first time through satellite imagery and seismometer data. The discovery marks the first observation, through modern recording tools, of the fault’s “creep,” which is the slow movement of a fault.

“It’s surprising because we haven’t seen [the Garlock fault] do that before,” Zachary Ross, an assistant professor of geophysics at Caltech and one of the study’s co-authors, tells TIME. “We haven’t seen it really do anything.”

Ross describes the movement as the slow detaching of land on the fault’s two sides, which typically stay locked through friction. The Ridgecrest earthquakes, the strongest of which was a 7.1 magnitude, caused the two sides to slide away from each other, Ross says. Ruptures in the Ridgecrest earthquake sequence ended just a few miles from the Garlock fault. “The fact that the Ridgecrest rupture terminated right next to the Garlock is what caused this behavior,” Ross explains.

Still, the researchers’ findings prompt more questions than clear conclusions or implications about future earthquakes. As Ross cautions, “We don’t really know what this observation means.”

Lucy Jones, a longtime seismologist who is not affiliated with the study, tells TIME it’s not unusual for faults to move after earthquakes, especially in their shallow parts. This movement does not indicate that an earthquake is about to happen on the Garlock fault, however. Earthquakes usually occur in the deeper parts of faults; while the recorded movement likely happened a few hundred feet below the surface of the fault, a major earthquake is likely to occur about 10 to 15 kilometers deep, according to Jones.

“The fact that we have a trigger slip accompanying a 7 [magnitude earthquake] is really common,” Jones says. “It’s like a passive response from the fault to the energy being released by the big earthquake.”

Prior earthquakes have been recorded to cause movement in faults, Jones adds. The Los Angeles Times reports the southern part of the San Andreas fault moved, for example, after a magnitude 8.2 earthquake occurred off the coast of southern Mexico in 2017. While such creeps following major earthquakes have been previously observed on the famed fault, they have not triggered further earthquakes, likely because they also occurred in shallow parts, according to Jones.

While it’s unclear whether the destabilization brought by the Ridgecrest earthquakes to the surrounding area will cause further big earthquakes, the Times notes that an earthquake along the Garlock fault could shake the region’s nearby oil and agriculture hubs, along with military bases. A magnitude 8 earthquake has the potential for grave disaster.

“The whole state of California would feel this one,” Ross says, noting the effects would be worse than the Ridgecrest quakes. “The direction of the shake will be more intense and felt over a larger area.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com