“I’m fascinated by the grandeur, the pompousness, the overmuch,” says Kara Walker. That sensibility fueled the American artist’s latest creation, Fons Americanus—a 13-meter-high fountain unveiled Sept. 30 in London’s Tate Modern museum. With a cast of characters and iconography reflecting the intertwined histories of Africa, Europe and America, Fons Americanus presents the brutality of slavery in a subversively joyful setting.

Walker is known for her ambitious work across mediums interrogating race, sexuality, slavery and identity; her 2014 installation A Subtlety was housed in Brooklyn’s Domino Sugar Factory, attracting over 130,000 visitors to the main giant sphinx sculpture. Fons Americanus is Walker’s fourth site-specific work, and it references classical British artists such as J.M.W. Turner and William Blake, as well as African-American historical figures including Emmett Till and Marcus Garvey.

The artist was inspired in part by London’s Victoria Memorial, a towering, majestic monument to the Queen who commandeered the British Empire. “I just got this jazzy feeling,” she says. “I’m interested in ways allegorical figures are misrepresentative of the thing they’re meant to symbolize.” Tributes to empire in the U.K., like Confederate statues in the U.S., have come under scrutiny in recent years, as observers reconsider how frequently immortalized figures also played key roles in the oppression of others. “Public space creates the opportunity for misinterpretation,” says Walker. “In some ways, I think my work is a misreading of empire.”

The contrast between the fantasy and the reality, the big and the small, forms the basis for Fons Americanus: “This is about the story I could tell with my own hand, which is perhaps second-class, and unseen or unheard,” says Walker, “and the story that is larger than it ought to be, than it has a right to be.” And while some monuments to empire have been dismantled, Walker is more concerned with what will take their place. “Who are we now, and what are we saying now as a people besides removing something?” she asks. “What do we build in its stead?”

Below, Walker explains the inspiration behind the different elements of Fons Americanus.

The Water

“It was all about the water, in a way,” says Walker. She was influenced by time spent in Rome, home to the spectacular Baroque Trevi Fountain. Early on, Walker decided that water would be an integral part of the installation and would symbolize the oceans that slaves were forcibly transported across, as well as a metaphorical connection between the shared histories and identities of Africa, Europe and America.

Venus

The fountain’s centerpiece references an 1801 propaganda artwork called The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies, which depicted the Middle Passage as a joyful journey. “The image of the Sable Venus is so appalling, isn’t it?” says Walker. It’s an icon that has mesmerized the artist for decades; she first referenced it in an early sketchbook when she was in art school, and later used it in her silhouette work. Walker’s Venus spreads her arms atop Fons Americanus and is reinterpreted as a liberated, celebratory priestess, drawing inspiration from Afro-Brazilian culture.

Pedestal figures

A sea captain partly modeled on Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint L’Ouverture appears on the front of the pedestal, joined by a kneeling man at his side, symbolic of a once-powerful slave owner now crippled by the rebellion. They are two of several figures overlooking water filled with drowning slaves and infested with Damien Hirst-inspired sharks. In presenting many characters and symbols, Walker wanted to create a “nauseating, miasmic sensation.”

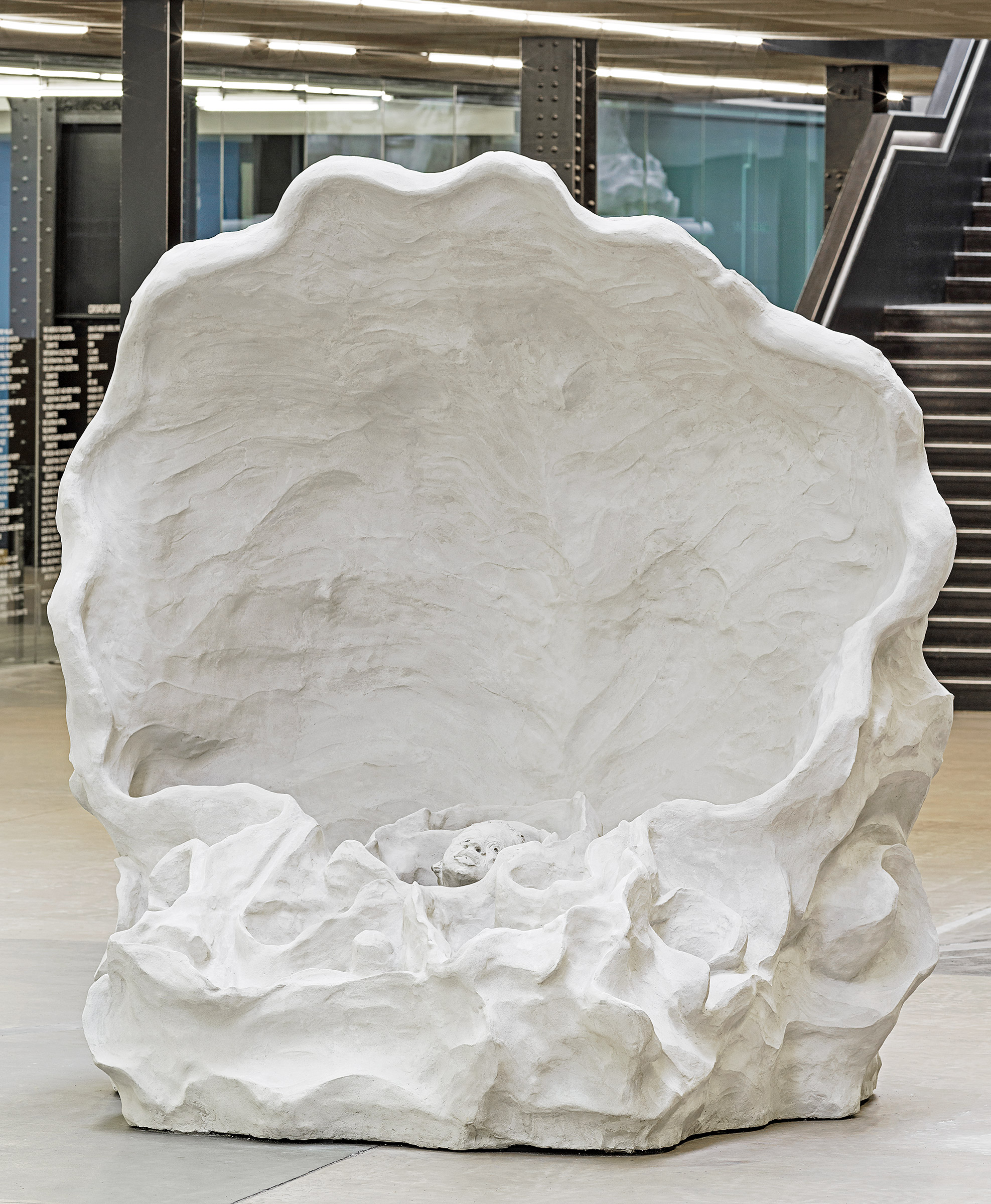

The Shell Grotto

The shell featured in the 1801 Sable Venus artwork is also referenced in the Shell Grotto, a smaller sculpture situated separate from the main fountain. In Walker’s reimagining, the scalloped shell houses the head of a small weeping boy almost submerged in water. He represents the ghosts of Bunce Island in Sierra Leone, a colonial slave-trading fortress through which thousands of Africans were transported across the Atlantic.

Fountain’s base

The ridge around the fountain’s base was designed with the public in mind, inviting viewers to engage with the work: sitting is “strongly encouraged,” so the piece can function “like a town square.” The full title of Fons Americanus is painted on the wall of the Turbine Hall, proclaiming that the fountain is in a “delightful family friendly setting.” “I do think that children are my best audience,” she says. “I think the conversation around race and slavery and history and culpability gets harder and harder to discuss as we get older, because we get into the nitty-gritty of what abuse looks like, and what cruelty feels like, and we don’t want to share that with children. But children get it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com