With unstoppable vigour, thickets of thistles three-foot-high were advancing over our land, engulfing acre after acre like the Day Of The Triffids. Every day, as my husband Charlie and I walked over what had once been arable fields on our family farm, we could barely believe what we were seeing.

Known as the “cursed thistle” this prickly weed — every gardener’s nightmare – spreads clonally, sending out penetrating tap-roots. In our case, however, using weed-killer was out of the question.

Several years into a pioneering project to “rewild” the land, we were no longer willing to use herbicides – or any of the pesticides, fungicides and chemical fertilizers that had once seemed so essential.

Giving up intensive farming on our 3,500 acres in the south of England had been a difficult, but unavoidable, decision. On our desperately poor soil — heavy clay — we rarely made a profit and had worked up an eye-watering overdraft at the bank.

Inspired by a rewilding project in Holland, we’d sold our dairy herds and farm machinery, stepped back and allowed nature to take the driving seat — the first major project of its kind in Britain.

Our neighbours had responded with a slew of ‘yours sincerely disgusted’ letters, complaining that rewilding was an immoral waste of land, an affront to cultural values, that we’d turned our home Knepp into an eyesore of noxious weeds and brambles. And now the great thistle invasion seemed to be proving them right.

We worried that the mounting opposition to the thistle outbreak might end our vision to establish a patch of self-wilded nature, a mini-wilderness in the heart of West Sussex before it had even begun.

Just when all seemed lost, out of a clear blue sky came a very different invasion. On a warm Sunday morning in May 2009, we woke to see painted lady butterflies streaming past our bedroom window at the rate of one a minute.

Outside, thousands upon thousands of them, migrating to the U.K. from Morocco, had descended on the swathes of creeping thistle to lay their eggs. As we approached, our dogs ran into the prickly cover, sending up puffs of orange and brown wings like autumn leaves. We walked for half an hour that morning, parting curtains of butterflies.

A few weeks later, spiky black caterpillars were swarming over the thistles, spinning silken webs like tents. The whole area took on the appearance of a chaotic army encampment. By autumn, the caterpillars had wolfed down the leaves, pupated and flown away, leaving our thistle fields in tatters. The following year, our 60 acres of creeping thistle had vanished entirely. Not only had Nature solved our prickly problem, but thanks to sitting on our hands, we’d been given a ringside seat at one of its great spectacles.

Knepp Castle Estate is just 45 miles from Central London, but now you might imagine you’re in Africa. Thorny scrub — hawthorn, blackthorn, dog rose and bramble — punched through fields that, only a few years earlier, were maize and barley as far as the eye could see.

The first thing that strikes visitors is the noise: the low-level surround-sound thrumming of insects. Then the symphony of bird song: the very air, it seems, is being recolonized with the sounds of the past.

Every year, more and more endangered species arrive — such as turtle doves, on the brink of extinction from Britain, and nightingales, whose numbers plummeted 91 per cent between 1967 and 2007. We have cuckoos, spotted flycatchers, fieldfares, hobbies, woodlarks, skylarks, lapwings, lesser spotted woodpeckers, yellowhammers, red kites, sparrowhawks, peregrine falcons, all five species of British owl, and the first ravens at Knepp for 100 years.

The speed at which rare species have appeared has astonished observers, given that our agricultural land was, biologically speaking, a wildlife desert in 2001, at the start of the project.

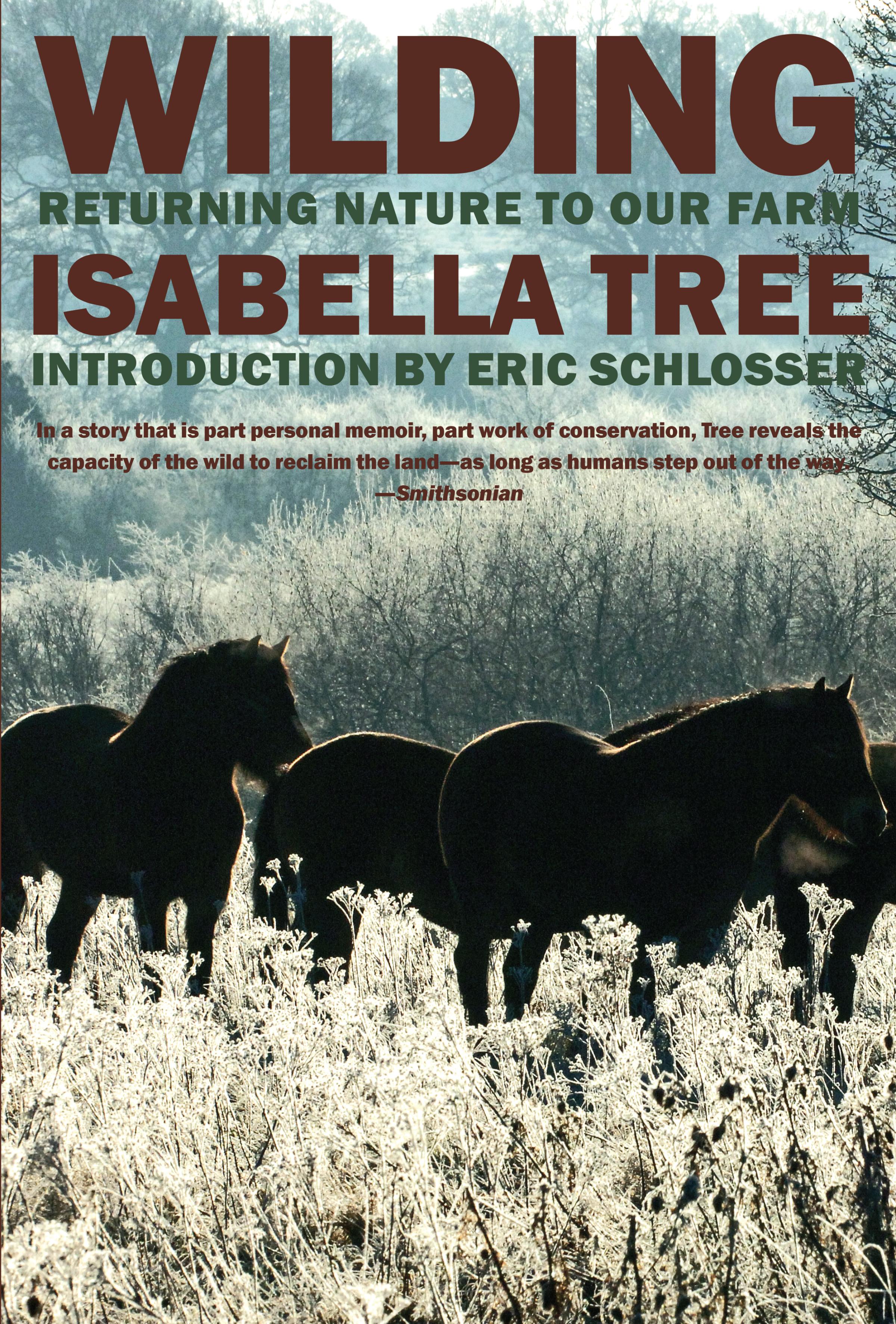

The key to Knepp’s extraordinary success is free-roaming herbivores – proxies of the megafauna that would once have roamed our land. In the right numbers – not too many, nor too few – large herbivores do battle with the emerging scrub, creating messy margins, opening up niches for other species. Old English longhorn cattle (representing their ancestor, the extinct aurochs), Exmoor ponies (proxies for tarpan, the primal horse) and Tamworth pigs (standing in for wild boar) have free-rein of the place, eating wherever and whatever they like. Together with roe, fallow and red deer, they browse, graze, rootle, puddle, dung and trample, rub themselves, snap branches and ring-bark trees. Their disturbance stimulates vegetation complexity and generates a dynamic, ever-shifting kaleidoscope of habitats – rocket-fuel for biodiversity.

The challenge for us as human beings, control freaks that we are, is to surrender the driving seat, and just sit back and watch what happens. Unlike conventional conservation which is all about targets and control, this is about shelving pre-conceptions, allowing natural processes to re-establish themselves. It’s about trusting nature to find its own way.

Originally, my husband and I had embarked on this project out of an amateurish love for wildlife. The switch to rewilding was funded, originally, by conservation grants but now we are close to being self-sufficient. Our income is derived from converting and renting out redundant farm buildings, selling organic, free-roaming “ethical” meat, and eco-tourism – African-style safaris, and glamping and camping in a wildflower meadow in the heart of the project. Increasingly, it seems, and the more urban we become, human beings are seeking out wild places, expressing what the great American biologist E.O. Wilson calls ‘biophilia’ – our innate need to connect with other living things.

But it’s not just biodiversity that is returning to Knepp. Our recovering ecosystem is unveiling solutions to some of the most pressing problems on the planet – like soil restoration, carbon sequestration, flood mitigation, and air and water purification. Our hope is that Knepp, and other rewilding projects now following in its wake, will help change entrenched mindsets about how we should manage the land, pointing the way to a wilder, richer future, one that benefits nature and us.

For if all these natural miracles can happen on our depleted patch of land in the over-developed, densely populated South-East of England, it gives hope for everywhere.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com