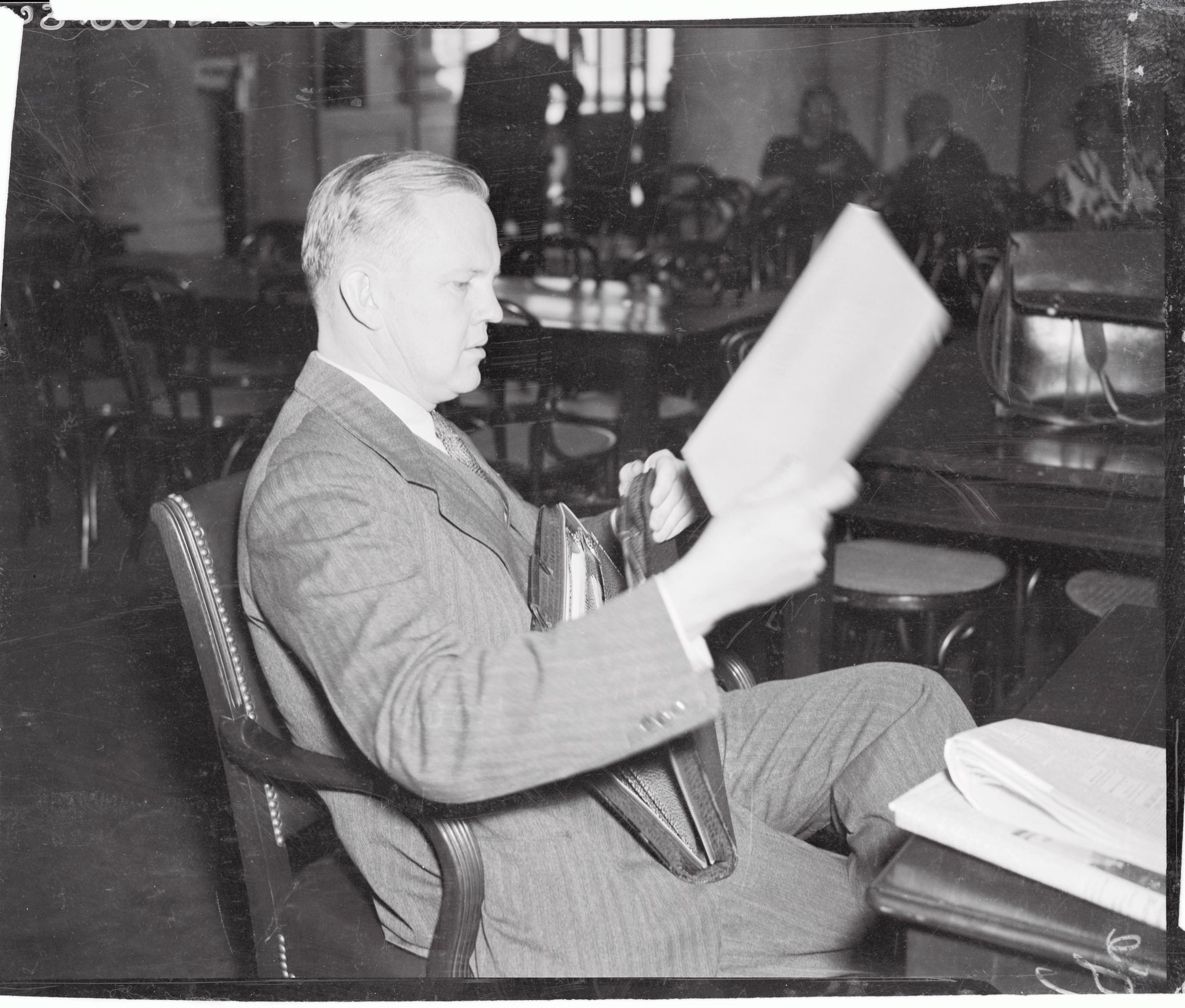

William Alfred Eddy did not look the part of super spy. No movie mogul would have cast him as a James Bond or a Jason Bourne. In his mid-40s, he had a limp, a receding hairline, a pudgy face and an expanding waist. Though he had served as a Marine in World War I, he dedicated his life after the war to the cause of peace. He became a missionary, sharing the Christian gospel with students in the Muslim world. But when the United States returned to war in the early 1940s, he again responded to his nation’s call to serve.

Eddy was one of dozens of missionaries recruited to help launch the United States’ first foreign intelligence agency, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Eddy was sent to Morocco, where the missionary could put his knowledge of the Quran, years of practice speaking Arabic and partnerships with Muslim leaders to good use preparing the way for Operation Torch, the 1942 Allied invasion of North Africa. As one of the most effective OSS field operatives, he soon became the target of Axis intelligence agents. Eddy’s American bosses warned him to take the greatest precautions or he would be returning home in a box, but he had other things in mind.

His most audacious undertaking included a plot to “kill,” as he described it, “all members of the German and Italian Armistice Commission in Morocco and in Algeria the moment the landing takes place.” In a straightforward and matter-of-fact memo, he told OSS head William Donovan that he was targeting dozens of people. He additionally ordered the executions of “all known agents of German and Italian nationality.” Never one to mince words, he called the proposal an “assassination program.”

To orchestrate his bloodthirsty plot, Eddy hired a team of Frenchmen. He planned to frame the executions as a “French revolt against Axis domination.” “In other words,” he explained to Donovan, “it should appear” that the dead Germans and Italians were “the victims” of a French “reprisal against shooting of hostages by the Germans and other acts of German terror,” and not an OSS operation.

At about the same time that he was recruiting French hitmen, he wrote to his family about the sacrifices he was making for Lent. He described the Easter season as “abnormal” this year. “I am certainly abstaining from wickedness of the flesh,” he confessed. With his wife thousands of miles away, that was not too difficult. “I haven’t even been to a movie since Lisbon, I don’t overeat any more, and I allow myself a cocktail at night, but never before work is all done.”

At the time, he was attending services at the local Anglican church. “It is a small community here” but the congregants knew that fellow believers around the world were joining with them in “the act of consecration and penance.” He told his family he was thinking of them, and that he was praying “that all of us come through to better days when mercy and charity again return to the earth.”

The calculus was clear for Eddy. To honor the death and resurrection of his Lord and Savior, no movies, no fleshly wickedness and not much booze. Pray for mercy and charity to return to earth. And in the meantime, covertly arrange for the murders of German, Japanese and Italian agents. The war, the assassination plot revealed, seemingly changed everything for religious activists-turned-spies like Eddy.

Or maybe it didn’t.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Maybe assassinating those who did the devil’s handiwork represented the logical culmination of their sense of global Christian mission, how they planned to bring peace and charity back to earth. In order for their postwar religious work to continue, they first had to defeat the evil that blocked their path. Perhaps for Eddy and dozens of other holy spies, serving a secretive, clandestine U.S. wartime agency tasked with defeating German and Italian fascism and Japanese militarism was another way, maybe the best way, to serve the very same Jesus they sought to emulate as missionaries.

But they were never quite sure. They occasionally wrote to their closest friends and family about their misgivings. They wondered in letters and diaries if they could honestly justify their work when they stood before the judgment seat of God.

American intelligence leaders had stumbled upon the fact that missionaries make great spies. They have excellent language skills, they know how to disappear into foreign cultures and they are masters at effecting change abroad. But while missionary spooks believed that their wartime work was necessary, they also wrestled with the moral ambiguities inherent in their actions.

Espionage is not like most occupations. It is not even like serving in the military. Operatives and agents manipulate, betray, bluff, bribe, cheat, con, dupe, forge, fake and hoodwink. Covert actions are always about ends; they are never about means. Evangelism is not like most other jobs either. Preachers and missionaries usually believe that God has called them specifically to their work. They embark on their careers with a sense of divine mission. They seek to build up the kingdom of God, not dismantle kingdoms of man. They seek the protection of the cross; they do not expect to double cross others.

During the war, missionaries trafficked in sin, exploiting the temptations that haunted their enemies or rewarding their informants with vice. They often hated what they felt they had to do and loathed the death and destruction that the war generated.

By the end of the conflict, American missionaries were gathering intelligence, keeping tabs on Axis agents, drafting plans to infiltrate enemy territory, partnering with insurgent groups, recruiting foreign hitmen and hatching assassination programs.

But these men of great faith had become men of great doubt. “We deserve to go to hell when we die,” William Eddy later lamented. “It is still an open question,” he continued, “whether an operator in OSS or in CIA can ever again become a wholly honorable man.”

The OSS’ religious crusaders, like Eddy, did what they did because they needed the United States to win the war in order to guarantee their freedom to work around the globe. But they did not want to bring any attention to their wartime actions. If word got out, how could the people they wanted to serve or convert ever trust the ones that insisted they were only doing the Lord’s work?

As a result, the U.S. government closely guarded the secret that missionaries and religious activists had become spies and assassins. Neither the missionaries, nor their religious agencies, nor American military leaders felt comfortable acknowledging the wartime lying, deceiving, manipulating and even killing that these religious-activist-operatives engaged in. The wartime stories of religious operatives have remained almost entirely hidden.

Until now.

Recently declassified government documents, papers revealed through Freedom of Information Act requests, and the discovery of private letters and diaries held by the children of wartime missionary spies have made it possible to tell this story for the first time.

The actions of the wartime religious activists illustrate the sometimes comic, sometimes tragic and sometimes profound ways that the founders of the United States’ pioneering foreign intelligence agency tried to use humans’ deep spirituality as a tool for war. Individuals, groups and nations’ religious commitments, American leaders discovered, intersected with global politics in powerful ways to motivate people to act towards many different goals. Modern American leaders are still struggling—and oftentimes failing—to understand this simple reality.

In the 1940s, the United States had few people with the skills and experience necessary to do effective intelligence work. Today, in contrast, the U.S. boasts an expansive, professional, modern Central Intelligence Agency. It does not need missionaries to achieve its goals.

We can be grateful that during World War II, American missionaries carried bombs and poison pills with their Bibles, and some even hatched assassination plots. We can also be grateful that today, they don’t need to.

Matthew Avery Sutton is the author of Double Crossed: The Missionaries Who Spied for the U.S. During the Second World War. New York: Basic Books (2019). He teaches history at Washington State University.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com