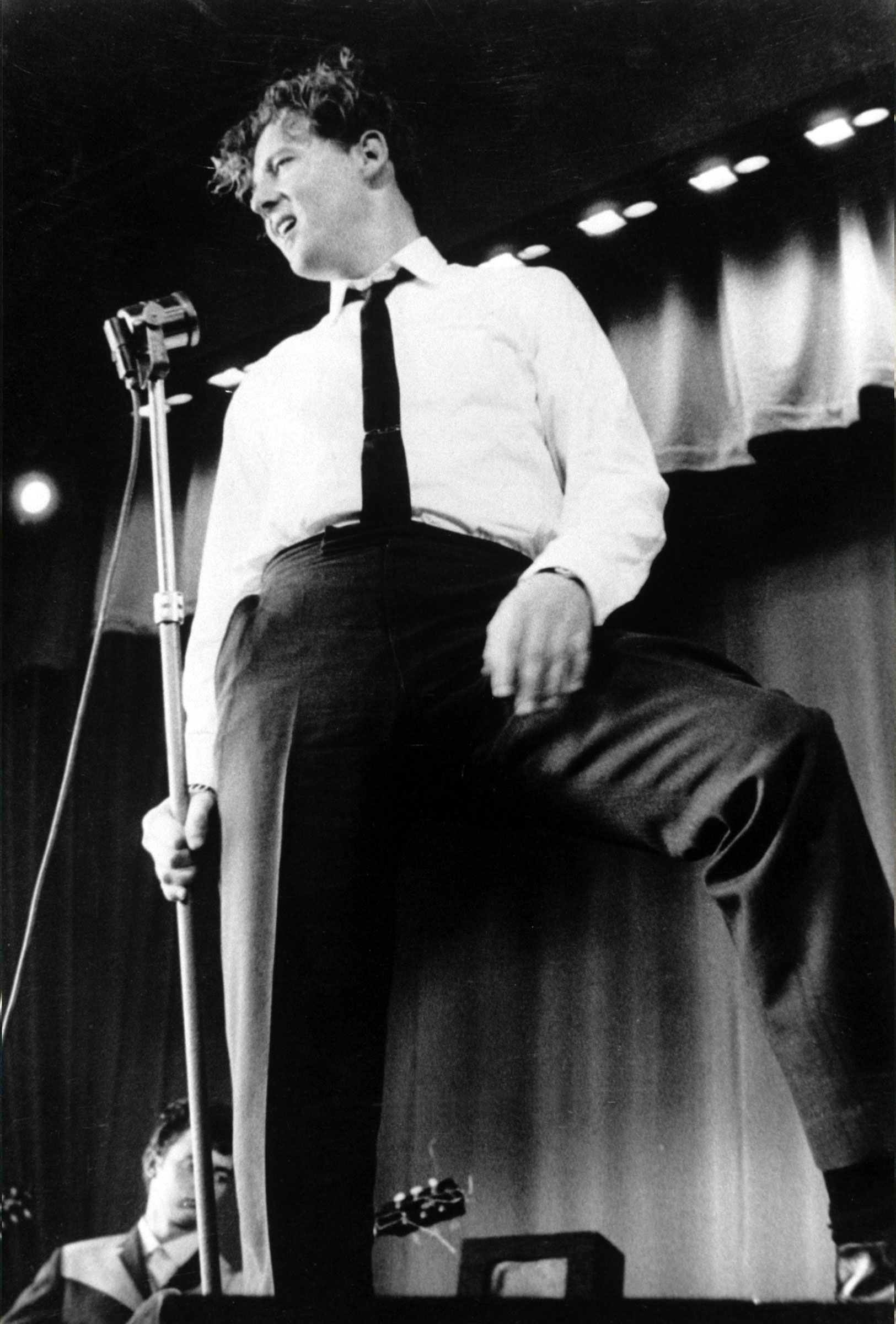

Like a ringmaster letting a lion out of its cage to terrify and thrill the kids at the circus, Steve Allen unleashed the 21-year-old Jerry Lee Lewis to a prime-time TV audience on his July 28, 1957, Sunday variety show. As Lewis ripped into his debut hit “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” the same startled excitement seized the folks at home as when Elvis Presley made his national TV debut on the Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey Stage Show 18 months earlier. The moment was that epochal.

Lewis, who died Friday at age 87, had a far briefer purchase on stardom than Elvis—not least because the rockabilly icon made as much trouble as he did music. The Killer, as he was known, was a charter member of the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame known for two songs (“Great Balls of Fire” was the other), and for marrying a 13-year-old first-cousin-once-removed—followed by a string of allegations of violence and abuse.

But he brilliantly defined the new music by revealing its tangled roots—in white and Black gospel stylings, in the boogie-woogie tickling and pounding of a barrelhouse piano, and in live performances of seismic unabashedness. Roy Orbison, who before becoming a pop star himself wrote songs for Jerry Lee, called him the best raw performer in rock ‘n’ roll history. Lewis unleashed the saints and demons of primal rock ‘n’ roll. When he finally wore himself out, he had secured a place next to Presley. He was rock’s pioneer pianist-singer, preacher-sinner—the great blond thug of music that might have been God’s or the Devil’s.

And if Elvis sent the royal family of 1950s pop music scurrying from the Winter Palace, Jerry Lee was Lenin—triumphant, and shocked to be suddenly sitting, smirking, raving on the old throne. Except JLL sat on a piano stool. Sat at the beginning, anyway. Then the fingers at the ends of those long, thin, untanned arms would attack the keys with the furiously proficient ardor of a Rubinstein or a Rubirosa. But let Nick Tosches, Lewis’ eloquent biographer, describe the event, in this passage from Hellfire:

“He sat at the big piano and he looked sideways at the camera, eyeballed it the way he has looked at those girls in the Arkansas beer joint, and then he began to play the piano and howl about the shaking that was going on. He rose, still pounding, and he kicked the piano stool back. It shot across the stage, tumbling, skidding… Steve Allen laughed and threw the stool back, then threw other furniture, and Jerry Lee played some high notes with the heel of his shoe. Then he stopped and looked at the camera sideways again. Neither he nor Steve Allen had ever heard louder applause.”

Those three TV minutes revealed Jerry Lee’s electrifying, near-electrocuting showmanship. But, honestly, the music was even better. The bass figure on the piano starts rumbling and, two beats later, J.M. Van Eaton’s cymbals join in. After the four-bar intro, Jerry Lee makes the vocal invocation: “Come on over, baby, whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on!” It’s a firm but liquid tenor, at times quavering with the infusion of the Spirit (perhaps holy, perhaps profane) that Jerry Lee heard in the Assembly of God meetings of his youth. Which is of course at the sundered heart of his music: a wrasslin’ match between the Deity and the Devil. Jerry Lee, whose cousin is the evangelist Jimmy Swaggart, has often said he is a man of God doing Satan’s work. His signature songs, beginning with “Whole Lotta Shakin’,” impart much of the thrill and dread of someone who has taken the Lord’s gift and twisted it into rock ‘n’ roll gold.

The song is a familiar 12-bar blues in the boogie-woogie fashion: two verses, a chorus (“Shake, baby, shake”), two verses of instrumental break (one featuring Jerry Lee amok on piano, his pummeling accentuated by an arpeggio as if he were running barefoot over the keys) followed by a reprise of the second verse with the inspired vocal filler, “We got a chicken in the barn/ Whose barn? What barn? My barn!”, then two softer, near-spoken verses—one with the ad-lib “You can shake it one time for me,” the second a little sermon on shakin’ (“All ya gotta do, honey, is kinda stand in one spot/ Wiggle around just a little bit/ And that’s when ya got something, yeah”). And, after this caressing, the final release, the sonic orgasm, the imperious “Shake it, make it shake!” as the piano pumps like a marathoner’s heart, the stool goes rush-stumbling across the floor and the listener soars or collapses in exhausted exaltation.

Goodness, gracious, great balls of fire!

On Thanksgiving Day 1957, he showed up on Dick Clark’s Bandstand. The other guests were the teen duo Tom and Jerry, later Simon and Garfunkel. For the kids in Philadelphia, Lewis sang his follow-up hit, “Great Balls of Fire.” He tore through the number and, toward the end, shook his long, slicked-back blond hair until it fell forward, virtually covering his face. He was suddenly a peroxided version of the Addams Family’s Cousin Itt. Hair wasn’t supposed to do that, not in the 50s. Gene Vincent’s was greasy, James Brown’s extravagantly pompadoured, Elvis’s as carefully coiffed as the 18th green at Augusta. Jerry Lee’s hair was a creature from a horror film, a redneck monster that arose, erupted and smothered its host. The Attack of the 50-Ft. Flaxen! Great bolls of follicles!

Again, though, it was the music that mattered. “Whole Lotta Shakin’ “ and “Great Balls of Fire” are among the most potent one-two punches any pop performer has launched and landed. And of these, “Balls” is certainly the greater. The first song was standard six-line, 12-bar boogie. “Great Balls,” written by ace 50s rock composer Otis Blackwell (of “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Fever” fame) and Jack Hammer, is a declaration of lust so impatient it needs only eight bars. It gets the job done in a majestically compressed 1min, 50sec.

Other improvements over “Whole Lotta Shakin’“:

Four bold notes, ascending by thirds, and then a break; the pattern repeated four times in the first verse, as JLL itemizes a lover’s complaint, “You shake my nerves and you rattle my brain…” Mid-rant, he muses that passion has its perverse perks (“You broke my will, but what a thrill”), before surrendering to ecstatic inanity: “Goodness gracious! Great balls of fire!” In the second verse, he punctuates the sexual agitation with three right-hand arpeggios. In the bridge, Jerry Lee’s left hand rumbles menacingly up to the break, when four-note poundings heighten the melodrama of the lyric: “You’re fine, so kind/ Got to tell this world that you’re mine mine mine mine!” Back to the verse, with more rumblings and eruptions—“C’mon, baby, ya drive me crazy”—and on to the two instrumental sections.

The first instrumental verse starts with a sassy, Jelly Roll Morton-style line, then bangs out another four-time, four-note, four-on-the-floor figure with, this time, four arpeggios. It’s how a sex-crazed Tex Avery cartoon wolf would express himself if he could play hot piano. Then the right hand pounds the same four high keys while the left hand describes a familiarly stealthy boogie-woogie figure, creeping up and down the lower register. We’re back into the bridge, Jerry Lee’s enunciation more forceful, and rampaging through the final verse. At “C’mon, baby, ya drive me crazy,” the chugging bass figure is briefly counterpointed by a cute hearts-and-flowers, silent-movie piano flourish, as if sentiment not sex were the theme of the story—he’s lying with his right hand, telling the truth with his left. A last “Goodness gracious! Great balls of fire!”, a final four-note blast, and it’s over.

Son of Sun

Elvis might have been anointed the King, the monarch of proto-pop, but Jerry Lee was Moloch, the pagan deity of the Middle East whose worship involved the sacrifice of children. The early-surly Elvis, once he fell under the stern tutelage of Col. Tom Parker, was processed and pasteurized into a nice young man who went Hollywood (and Vegas) almost as soon as he became a star. Jerry Lee, who would tolerate no image-makeover Svengali, wore the musk of venereal danger, styled himself as a reckless teen girl’s dream and her mom’s nightmare. His nickname was “The Killer,” and who knows how close he came to living down to his legend?

When asked to compare himself and Elvis, Jerry Lee used to say, “We are entirely different performers. ‘Bout the only thing we got in common is that we’re from Tennessee.” Except that Presley was from Tupelo, Miss., Jerry Lee from Ferriday, La. He was born Sept. 29, 1935—274 days after Elvis. Among his cousins were Swaggart and Mickey Gilley, who much later would mimic Jerry Lee’s style and sell far more singles.

From the beginning, Jerry Lee was an addict to music: inhaling all kinds, then reproducing and blending it on the family piano, where he would do his little boogie-woogie every day. When he was 20, Lewis made the rounds of Nashville record companies, but the belligerent weirdness showed through. The Grand Ole Opry turned him down then, and for years thereafter. Of the town’s career-makers, in the post-Elvis feeding frenzy, JLL recalled that, “They said, ‘Well, now, you change your act to a guitar and you might could make it.’ I said, ‘You can take your guitar and ram it up your a–.’”

Jerry Lee was, after all, a consummate keyboard man, with the unruliest left hand in the business. If 50s record producers thought they could make a mint with a white kid who sang like a Black man, why couldn’t the next big thing be a white kid who played like a Black man?

Sam Phillips, Elvis’‚ mentor at Sun Records, signed JLL to play piano for a Carl Perkins session on Dec. 4, 1956. That’s when Elvis and Johnny Cash dropped by, the four sang a bunch of gospel numbers and pop songs, and the tapes were released decades later, with the singers billed as The Million Dollar Quartet. Soon, JLL was worth at least that much to Phillips. He sold records by the tons, induced puberty in America’s young and shrugged off the charge by Jerry Lewis (born Joseph Levitch) that Jerry Lee had stolen his name!

Jerry Lee often said that pop music had produced only four supreme stylists: Al Jolson, Jimmie Rodgers, Hank Williams and himself. (Al Jolson?) By early 1958, JLL could reasonably expect he might soon be the most popular of the four. “Breathless,” his follow-up to “Great Balls of Fire,” was chugging up the charts. His next single would be the theme song to a (minor) Hollywood film, High School Confidential. And in May he would begin a headlining tour of Great Britain. A star was born. A star prevails.

Cast out of the spotlight

A star fell.

In London he acknowledged that the young lady accompanying him—Myra Gale Brown, the 13-year-old daughter of his cousin J.W. Brown (who played bass in his touring band)—had been his wife since Dec. 12, 1957. Jerry Lee, 23, was used to hell breaking loose around him, but usually he was the one who invoked the demons. Now he looked pale and defenseless in the tabloid press’s glare. The Rank theater chain canceled his bookings, and he returned to the U.S. to find the reception no kinder. Top-40 radio stations exiled Jerry Lee’s music, and Sun Records issued his next single, “Lewis Boogie,” as the B side of a derisive novelty number called “The Return of Jerry Lee,” which intercut snippets of his records with a reporter’s mock-interrogation. “What did Queen Elizabeth say about you?” “Goodness gracious! Great balls of fire!”

Musically speaking, it was a damn shame. “Lewis Boogie,” in its rollicking rockin’ propulsion, fully merits a place next to his two signature hits. It begins as abrupt as wartime reveille: four four-note phrases, each an octave lower than the preceding, on a piano that sounds a little flat in the upper registers. Then JLL races into his vocal. Of course there’s a slew of arpeggios (eight, to the all-time record 11 in “Great Balls”) and the satyr-singer’s invocation of the magic moment “when your hips start rockin’/ Honey, and your knees start knockin’.” For a transcendent 1min, 58 secs., find the song on the Jerry Lee album 25 All-Time Greatest Sun Recordings.

Through the ignominy years, Lewis never slunk into retirement. If the gigs paid a few hundred dollars instead of the $10,000 he once earned, he was man enough to show up. He had some country hits in the 60s, and in 1968 played Iago in the L.A. production of an Othello musical called Catch My Soul; he spoke the lines word-perfect, in his deep bayou drawl, and stole the show. “This Shakespeare was really somethin’,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “I wonder what he woulda thought of my records.”

‘The Killer’

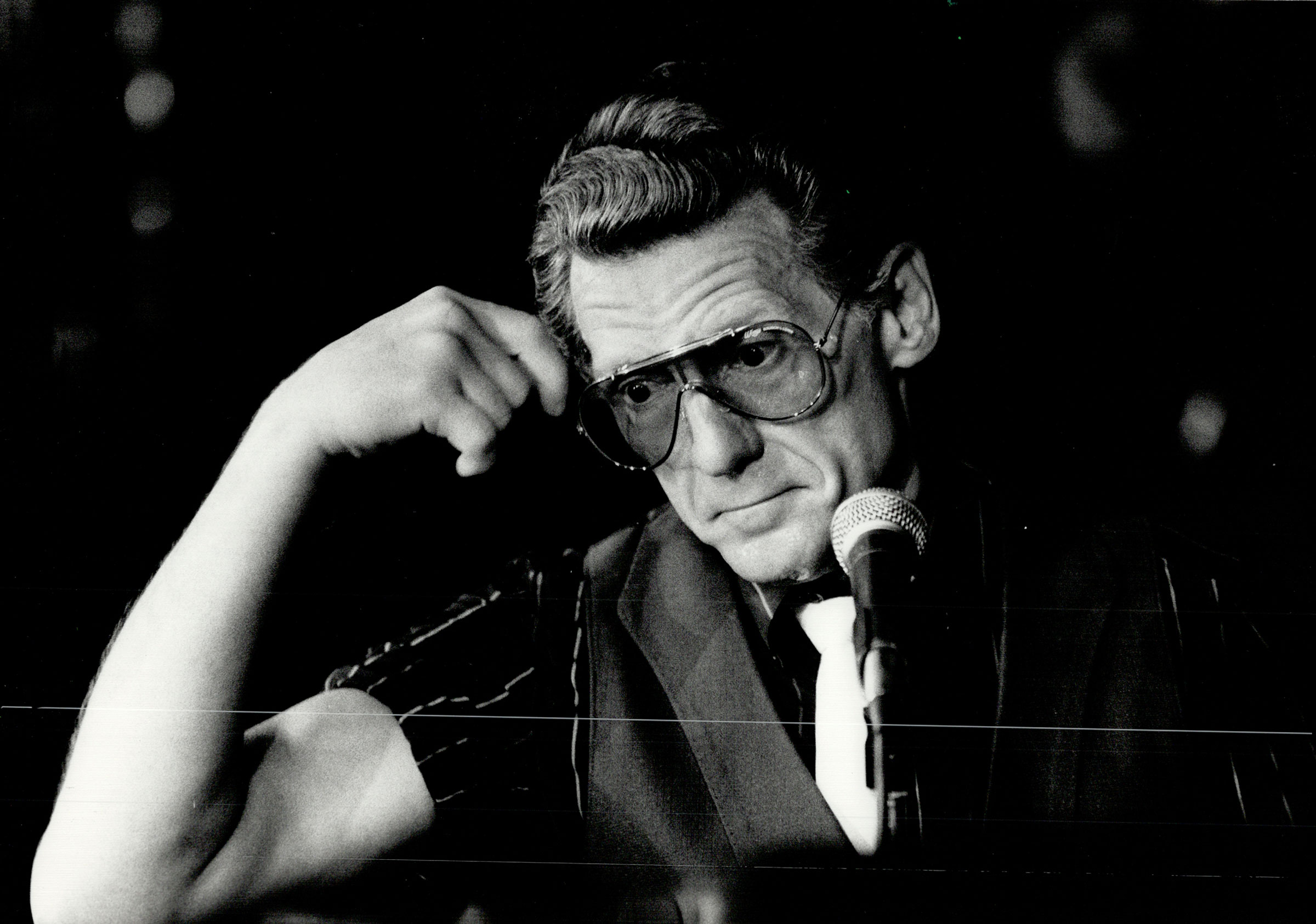

Why did Jerry Lee Lewis take so long to die?

He abused himself with pills and booze for most of his adult life. He nearly died in 1981 from a ruptured stomach. He shot his bass player Butch Owens in the chest—accidentally, it is said; Owens survived. But Lewis’s family tree is full of untimely death. His elder brother Elmo was run over by a truck when JLL was three. His eldest son Jerry Lee, Jr., died at 19; car crash. Steve Allen Lewis, his son by Myra, died at 5 in a swimming pool. His fourth wife, Jaren Pate, also died in a swimming pool, in 1982. His fifth wife, Shawn Stephens, died a few months into their marriage; it was ruled a methadone overdose. But that doesn’t explain her “bruised, bloodied corpse,” found by police in the bedroom of the Lewises’ Nesbit, Miss., mansion. Or the comment Lewis supposedly made to Stevens’ sister Denise. As she told the Detroit Free Press: “I said, ‘What happened?’, and Jerry said, ‘Your sister’s dead, and she was a bad girl.”

Jerry Lee wasn’t the only rock star to endure or sow tragedy. Elvis’s twin brother died at birth. Berry was convicted of having sex with a 15-year-old (not his wife) and served three years in jail. Orbison married the 15-year-old Claudette Frady, who died 11 years later in a motorcycle crash. But Jerry Lee had such a run of horrific behavior and misfortune that the frequency and enormity of them begin to seem … unseemly.

It surely affronts plausibility that Lewis was the last man standing from the Million Dollar Quartet. He’d been flip when he heard Elvis had died at 46 in 1977, saying, “Another one outta the way.” But Orbison succumbed in 1988, at 52, and Perkins 10 years later; he was 66. When Cash died in 2003, at 71, Lewis said in wonder, “You know, I’m the only one left.” The night of his friend’s death, JLL interrupted his Jacksonville, Fla., concert to perform the sacred song Vacation in Heaven in Cash’s honor.

That might have been an ironic choice of tunes, coming from the Hellfire Kid. But for years after that, he kept on his brutal regimen of one-night stands, figuring his could keep on playing till Judgment Day. Perhaps God or the Devil had other plans for the Killer. Or perhaps Jerry Lee saw them still wrasslin’ for his soul, and as referee he refused to call off the match. Then again, it could be he was just too damn stubborn to pack it in. He wanted outlive the other rock ‘n roll icons on the Oldies circuit and finally seize the throne—the jewel-encrusted piano stool—he always believed was his.

Well, now we can say that the Killer deserved it. He gets our Deathtime Achievement Award for embodying so much of what was feral and profound about rock ‘n’ roll. He knew its varied roots and how to tap them. As he announced at the conclusion of his belated, heroically defiant debut at the Grand Ole Opry in 1973: “Let me tell ya somethin’ about Jerry Lee Lewis, ladies and gentlemen. I am a rock-’n’-rollin’, country-and-Western, rhythm-’n’-blues-singin’ mother f—.”

Satan couldn’t have said it better.

Richard Corliss was TIME’s film critic. He died in 2015.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com