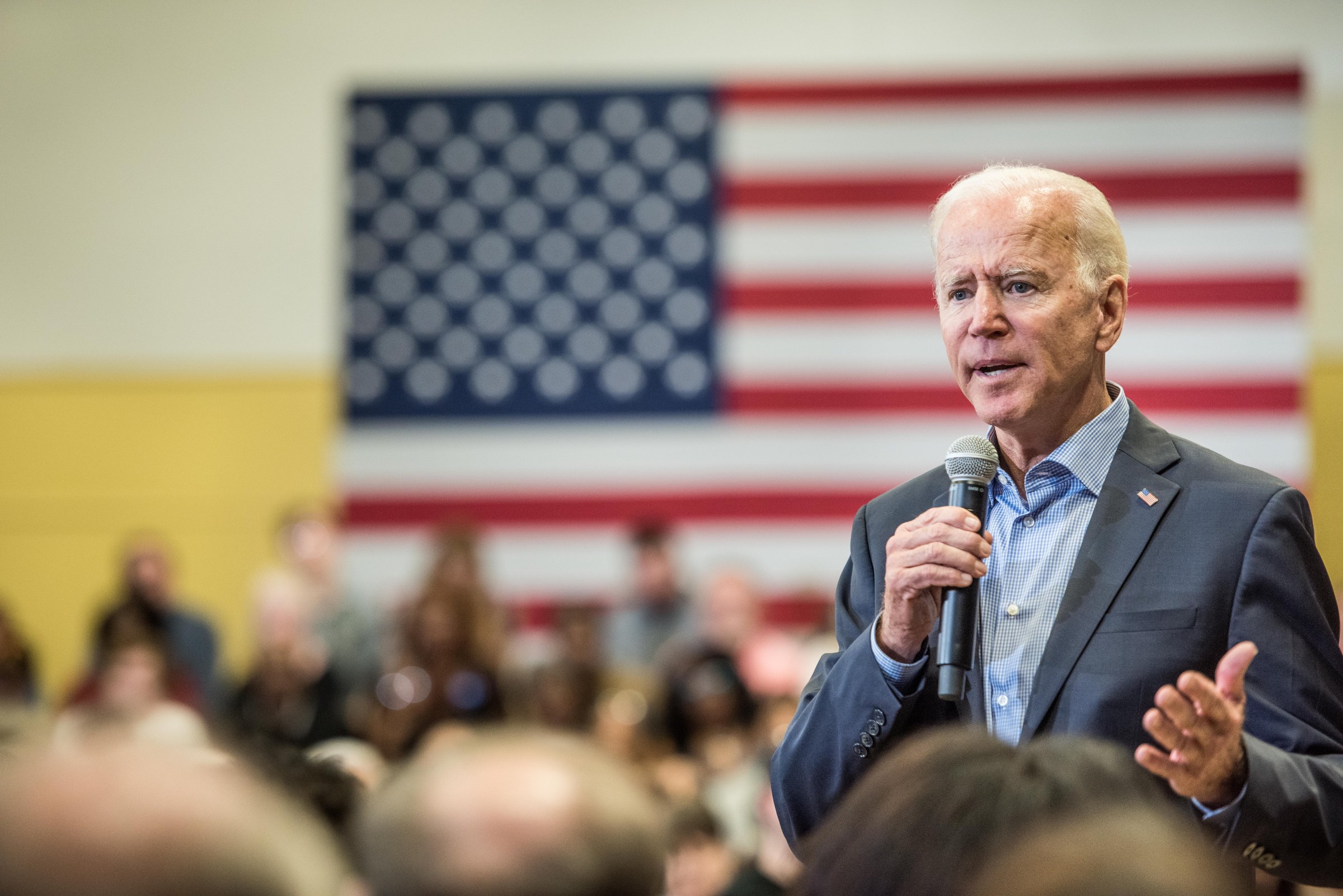

Joe Biden sincerely did not understand the hullabaloo about a Washington Post story detailing how the former Vice President had mangled facts about U.S. soldiers and his own role in honoring them. For the life of him, he told his staffers on Thursday between campaign stops in South Carolina, he could not process why journalists, let alone the public, saw this as a problem. He had meant well enough, Biden told aides. The campaign wouldn’t dignify it with a proper statement.

When it came time to do two previously scheduled interviews on the road, Biden stood defiant against any suggestion that he did, in fact, have his facts wrong. He told The Post and Courier of Charleston, S.C., that he had the “essence of the story” right. And he told a Washington Post podcast that he saw nothing wrong with his retelling, despite having misstated his role at the time, the military branch of the hero, the year it took place and what actually happened.

“I don’t know what the problem is. I mean, what is it that I said wrong?” he asked the Post‘s Jonathan Capehart. (Biden, for his part, had also said he would not read the story.) After all, President Donald Trump has flubbed the facts more than 12,000 times, according to the Post’s ongoing tally. Surely, Biden deserved some slack.

Thus is the state of the frontrunner for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination as the unofficial start of the fall campaign arrives this Labor Day weekend. The 76-year-old Biden, whose 1988 bid for the same nomination ended in a plagiarism scandal, is still having trouble mastering basic facts in stories that ostensibly star him.

He has already weathered one round of plagiarism charges in this campaign, brushed past complaints about his non-sexual physicality with friend and stranger alike and delivered two uneven debate performances. The ability to defeat Donald Trump — the centerpiece of his campaign rationale — has become less sturdy as polls indicate other candidates, too, could beat the incumbent in a hypothetical match up. Biden remains the polling leader, although nowhere near as comfortably as when he entered the race in April and then had a rally-style kick-off in May. The once-perceived inevitable nominee has been proven as fragile as his critics warned.

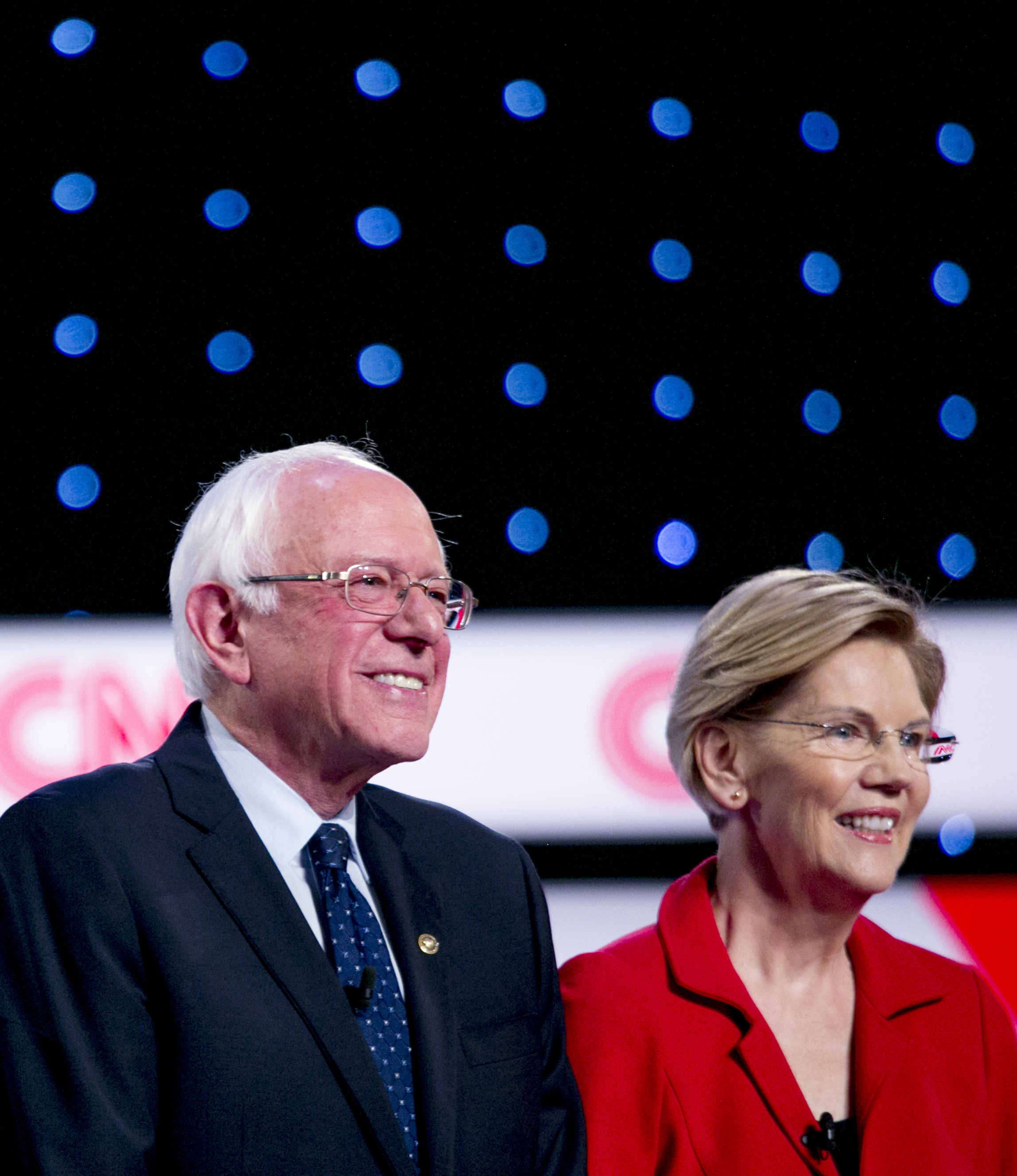

Which explains why, 22 weeks before Iowa hosts the lead-off caucuses, most of Biden’s rivals are not forlorn. Elizabeth Warren is positioning herself — through an impressive political machine with few peers — to possibly win both Iowa and New Hampshire. Bernie Sanders knows the history, too; he and Warren both hail from states that border New Hampshire, and voters there have never passed on a chance to back a New Englander. In South Carolina, where six-in-10 Democratic primary voters are expected to be black, contenders like Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Julián Castro see potential. And then there’s Pete Buttigieg, whose fundraising shows little sign of limitations; 300 people on payroll, including 70 in Iowa and 50 in New Hampshire.

In other words, the Labor Day campaign launch of the frenzied fall push comes at a moment of tremendous peril for Biden, potential for his rivals and promise for Democrats who, above all else, want to beat Trump. First, though, they have to settle among themselves who will get the chance to do so. And, at the moment, it is possible to see paths for most of the mainstream hopefuls.

Biden remains the most plausible candidate, having built up chits over decades in politics dating back to his first election in 1970. But the last week has left some aides more worried than ever. First, during the same New Hampshire day when he bungled war stories, he also told the familiar story about how he entered politics: explaining that the turmoil of 1968, which saw the assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., sparked his civic interest. He then asked his audience at Dartmouth College to imagine the raw emotion had it been Barack Obama who was assassinated.

Biden’s critics and even some allies cringed. It’s never a good look to summon a theory about the assassination of the nation’s first black President, especially if Biden was the constitutional successor.

Biden aides sprang to action, in a way not before seen during this campaign, to call out anyone who was being critical or snarky — and to shame journalists who had tweeted the quote without context. It was an aggressive show of a coordinated rapid response from Biden’s Philadelphia headquarters, and it quieted some jitters among Biden allies.

Then came a poll that showed Biden’s numbers tanking. Monmouth University’s survey — since described by its pollster as an outlier — showed Sanders and Warren each at 20% and Biden at 19%. Biden aides nervously dismissed it as a statistical aberration, which apparently it was. Still, though, it caused some nervous ticks among Biden donors and activists.

The top ranks of the Biden campaign, though, insist the campaign will move ahead as planned. Biden plans stops on Labor Day at Iowa union picnics and two days later will return to Stephen Colbert’s The Late Show stage, where he gave a remarkably frank interview two years ago about his emotional status.

Meanwhile, Biden rivals are churning through events and cash. They may lack that national name ID and fundraising Rolodex, but they have optimism in bounds. They’re not without reason. At this point in 2007, Hillary Clinton was at 37% in Real Clear Politics’ average polls, while Barack Obama was at 21%. Obama, of course, prevailed. Still, it was a much smaller field.

All of this speaks to Biden’s advantages. Unless — or until — his rivals coalesce in an anti-Biden bloc, he may be impossible to stop. Only candidates who win 15% support are eligible to win delegates to the nominating convention in Milwaukee. A brokered convention is entirely possible, which is why Buttigieg delegate chief George Hornedo has been aggressively working the phone with super delegates, who, in a twist of irony, may end having more power than in 2016 to actually decide the nomination. The rules changes passed after 2016 strip super delegates, the party insiders who can back anyone at the convention, of their votes on the first ballot. But if a brokered solution cannot be found, they may end up being called upon to sway the results. The fallout may be nothing short of chaos.

This is why Biden’s backers are trying to win the nomination outright, on that first ballot. Still, the last week shows just how fragile Biden’s advantages are at this moment.

The fall campaign will certainly test those advantages further still.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com