To be a Clevelander is to speak two languages. There is the tongue of the country, and then a distinctive local idiom known to linguists as Browns bemoaning. A fine example of this was on display recently at the Flat Iron bar, in the shadow of the rusted rail bridges that cross the Cuyahoga River, as barber Nick Hilf rattled off the litany of heartbreak that has befallen the city’s beloved NFL team. The Drive: when Denver’s John Elway marched downfield to tie the 1986 AFC championship game, which the Broncos won in overtime. The Fumble: when Cleveland’s Earnest Byner coughed it up in the AFC title game the very next year, again against the Broncos, again costing the Browns a shot at the Super Bowl. And, of course, the Move: when team owner Art Modell relocated the Browns to Baltimore for a sweetheart stadium deal. Thus, the team that for 50 years had been the Cleveland Browns became the Baltimore Ravens. The current Browns began play in 1999 using the same name and logo of the once proud original franchise. And the two decades since have not been pretty. “I cried when they left,” says Hilf over a pour of bourbon. “And it’s been freaking miserable for the last 20 years.”

Since the Browns came back to football-mad northeast Ohio, the team has had just two winning seasons and one playoff appearance (which it lost in the wild-card round, to hated rival Pittsburgh). No NFL team has a longer active playoff drought. In 2017, the Browns didn’t win a single game, becoming just the second team in league history to finish 0-16. And Cleveland finished 1-15 the season before. This is a run of dubious achievement without peer in professional football.

Yet as the Browns opened training camp this summer, a surprising quality could be detected across the city: optimism. The Browns are actually expected to win more games than they’ll lose. Sports Illustrated and ESPN’s Football Power Index predict that the Browns will win their first division title in 30 years.

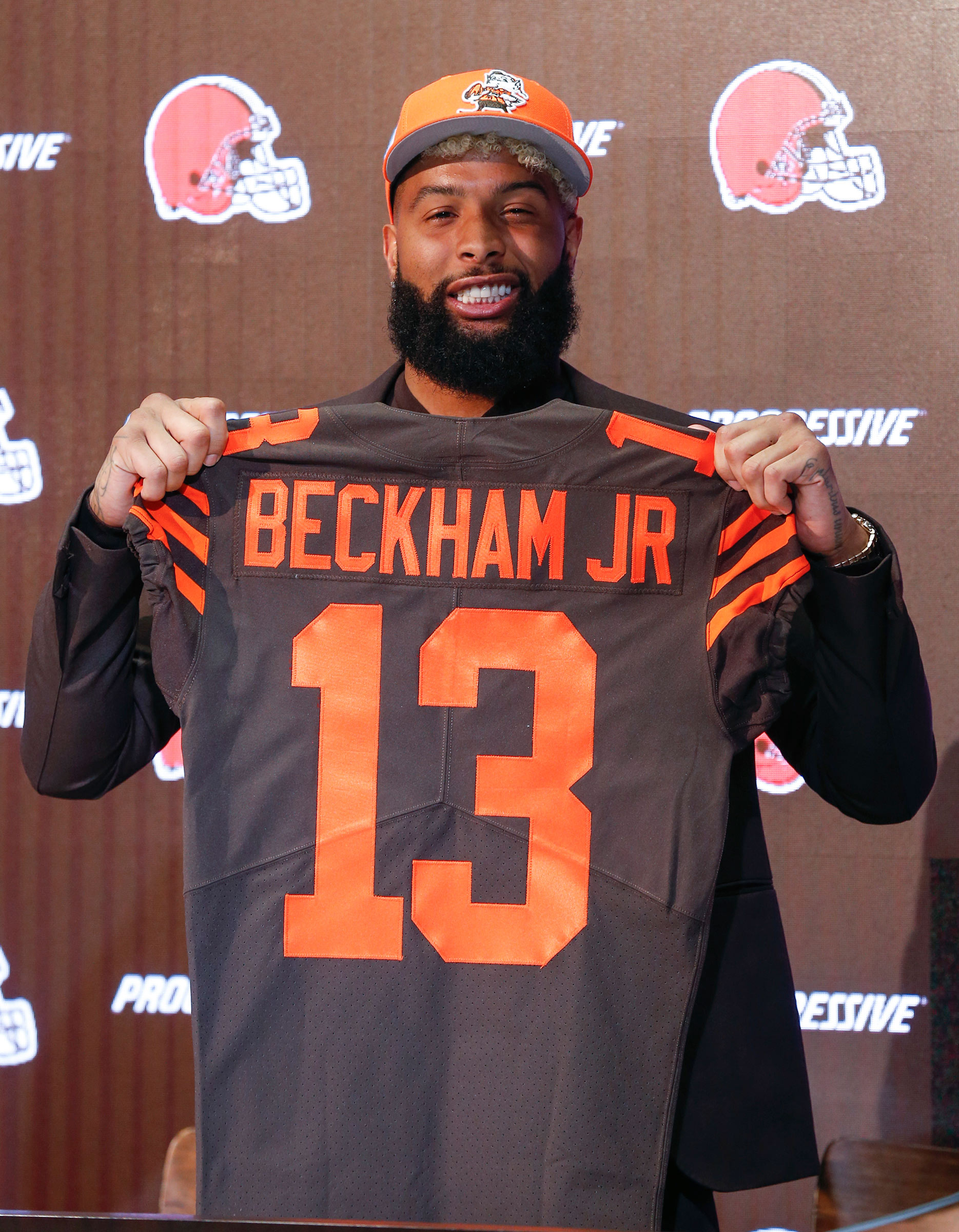

Thanks to an infusion of young talent led by brash second-year quarterback Baker Mayfield, the Browns, who finished 7-8-1 a season ago, have a swagger usually reserved for teams from bigger markets and with better pedigrees. Indeed, their prized off-season addition was the former New York Giants star Odell Beckham Jr., who traded the bright lights of Broadway for the lower-key charms of Playhouse Square. Amazingly, it is not hyperbole to say that the Cleveland Browns, whose logo-less burnt-orange helmets, icy home on Lake Erie and hard-luck history embody gritty, lunch-bucket football, have become the NFL’s sexiest team.

“We’re like the guy in high school who everyone made fun of, and never got the girl, showing up to the 10-year reunion in a Ferrari, sticking his chest out and dancing around,” says Chris McNeil, a purchasing manager for a steel fabrication company who organized a parade to mock the 0-16 season. “If any fan base deserves to be that guy for once, it’s us.”

The Browns’ resurgence mirrors the shifting outlook of their home city. Once derided as “the Mistake by the Lake,” Cleveland rebounded following a postindustrial exodus of jobs and people that accelerated in the 1970s. In the past year alone, home prices and many employment metrics have trended up. Largely because of the vaunted Cleveland Clinic, the metro area is the densest health-science labor market in the country. According to one analysis, the region’s year-over-year per capita income-growth rate was the fifth highest of the nation’s 40 largest metro areas, behind only New York City; San Jose, Calif.; San Francisco; and Denver. The downtown population has risen 77% since 2010, and construction cranes dot Euclid Avenue, a major thoroughfare. Cleveland has taken a star turn as host of the 2016 Republican National Convention and this year’s baseball All-Star Game. The NFL draft is coming to town in 2021.

To many close observers, no small measure of credit for this revival rests with LeBron James, the Akron native who led the Cavaliers to the NBA championship in 2016–Cleveland’s first title in any major sport in more than 50 years. (Baseball’s Indians have now gone 70 seasons without a World Series win–the longest streak in the game.) But James has since decamped for Los Angeles, and for all the excitement over finally winning something, it’s football that really speaks to many Clevelanders’ souls. Pro football began in Ohio, with some teams sponsored by the mills and plants that gave the Rust Belt its name, and is still followed with a devotion just shy of religion. “The drought is over,” says Richey Piiparinen, an urban theorist and researcher from Cleveland who specializes in the relationship between where we live and how we think. “But have we really had a full glass of water? No.”

Paul DePodesta knows all about the expectations. The Browns hired DePodesta as chief strategy officer in 2016 with the mandate to build a turnaround plan that would finally end the losing. He was an unconventional choice: DePodesta spent his career in baseball operations, including a stint with the Oakland A’s that led to his being portrayed by Jonah Hill in the Oscar-nominated film Moneyball. He worked for the Indians earlier in his career and recalls telling a lifelong Clevelander after the team clinched the 1997 pennant that the city seemed electric. He says the man told him that it would pale compared with what it would be like if the Browns ever won. Mind you, the Browns had just left for Baltimore. The team didn’t even exist.

To shape his restoration plan, DePodesta picked the brains of experts inside and outside the game, including Richard Thaler, a Nobel Prize-winning behavioral economist who in 2013 co-wrote a paper finding that impatient NFL teams overvalued early picks in the annual college draft. That influenced the Browns’ eventual strategy of acquiring future draft picks and clearing salary-cap space.

Analytically minded teams in other sports have successfully gutted the present to build for the future, a practice often derided as “tanking.” But in the NFL, Cleveland’s plan to do the same was fairly novel. In theory, the league’s hard salary cap creates parity by putting teams on equal footing and giving each a plausible shot at the Super Bowl.

The pain, however, was harsher than expected; the 1-31 stretch cost general manager Sashi Brown his job. He was replaced in late 2017 by John Dorsey, a former pro linebacker who spent 26 years working in NFL front offices. “We felt like we wanted to have more of that traditional football presence,” says Browns executive vice president JW Johnson, the son-in-law of Browns owners Jimmy and Dee Haslam.

In one of the first signals that Cleveland was ready to start at least trying to win, Dorsey traded draft picks for three established talents, including wide receiver Jarvis Landry and safety Damarious Randall, on the same day. “You do that and it begins to send a message to players across the NFL and the agent community,” Dorsey says from his golf cart at the Browns’ practice facility during training camp. “You know what? Cleveland is slowly going to get this thing turned around.”

Thanks to moves made by the previous front office, the Browns had four of the first 35 picks in the 2018 draft, including the first selection. Not every fan wanted Mayfield, who reminded them of another former Heisman Trophy winner, Johnny Manziel, who flamed out with the Browns. Like Manziel, Mayfield was cocky and undersized, and had been arrested for disorderly conduct while in college. “My worry,” says Eddie Miller, a brewery manager in Granville, Ohio, “was that Baker Mayfield had an a–hole problem.”

If Dorsey had similar concerns, Mayfield assuaged them during their first meeting. The general manager’s first question for Mayfield was “So, you like food trucks?” Mayfield, who had been taken into custody near a food truck, laughed. “He’s a weirdo, so his tests are a little bit different,” says Mayfield of Dorsey’s evaluation process. “If I got frazzled, wasn’t able to handle myself and let it affect me later on, I don’t think they would have drafted me. A short-term memory for a quarterback is pretty important.”

Mayfield showed there was substance behind the strut. In his first game as a rookie, he came off the bench to rally the Browns to a home win over the New York Jets–Cleveland’s first victory in 21 months. “The energy of the stadium, the whole energy of Cleveland, just changed,” says Landry. “Everybody had that ‘Here we go’ type feeling.” After Mayfield threw for three touchdowns in a win over the Atlanta Falcons in November–one of an NFL-rookie-record 27 he threw over the season–he informed reporters that he woke up “feeling pretty dangerous.” That quote now adorns a mural in downtown Cleveland.

In Beckham, Mayfield has a weapon as electric on the field as he is off of it. Beckham was a three-time Pro Bowler for the Giants, but he also provided endless fodder for the Big Apple tabloids. He partied before a playoff game, got suspended for scuffling on the field, criticized his teammates and coaches. Beckham tells TIME that his reputation as a troublemaker is “created by a lot of bullsh-t,” and he sees the upside of leaving New York for Cleveland. “The only way I would be able to start over is to be traded somewhere else,” he says. “You’re always going to be reminded of your past. It’s always going to be a reliving, recurring thing. So I’ve reset myself. I’ve forgiven myself for the things that I’ve done, regardless if anybody else does.”

Cleveland also offered a do-over to running back Kareem Hunt, who led the NFL in rushing yards as a rookie in 2017 but was released by the Kansas City Chiefs last season after video emerged of him getting into a physical altercation with a woman in the hallway of a hotel and apartment building. On the tape, Hunt can be seen shoving and kicking the woman. No criminal charges were filed, but the NFL suspended Hunt for the first eight games of this season. “When you spend time with Kareem, you see that he has the ability to be the kind of man he needs to be,” says Browns co-owner Dee Haslam. “He has a lot of work to do.”

The heightened expectations have brought heightened attention. The Browns have added some 12,000 season-ticket holders since the start of last year, and the average age of the new fans is 36, according to the team, compared with 54 for the prior fan base. There are now 390 “Browns Backers” fan clubs, with almost 62,000 members in 48 states and 13 foreign countries. Membership has jumped 31% since before Mayfield was drafted. CBS has assigned its top broadcasting team to the team’s season opener, on Sept. 8, and three of the Browns’ first five games will air in prime time, on national TV. “Hell, they were probably banned from being on TV in the past,” jokes Cleveland’s four-term mayor, Frank Jackson. “Waste of valuable airtime.”

This is the point at which a reality check is in order. “You’re not a Cleveland fan,” says McNeil, organizer of the 0-16 parade, “unless you’re thinking in the back of your head, How are we going to screw this up?”

Cleveland’s rookie head coach, Freddie Kitchens, is quick to remind his players–and anyone else within earshot, including visiting reporters–that the Browns finished last season under .500. Only the team’s punter, Britton Colquitt, has played in the Super Bowl, which he won with Denver. “We’ve got a bunch of good players,” Kitchens tells TIME. “But collectively, individually, they’ve never won anything.”

Mayfield echoes his coach. “It’s a process,” he says. But his receiver, Landry, takes a different tack. “I’m not going to say, ‘Be patient,'” says Landry, who made his fourth Pro Bowl last season. “They’ve been patient long enough, you know what I mean? I say it with complete confidence. It’s time.”

Landry’s message may be the one more in tune with a city that still struggles with high poverty and crime rates but is rewriting its story. “We’ve been through that cycle of bemoaning,” says Mayor Jackson, from his large office on the second floor of city hall. “We ain’t got time for that. They win, they win. They lose, they lose. But the expectation is that they will do well. And people are going to hold them to that.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sean Gregory/Cleveland at sean.gregory@time.com