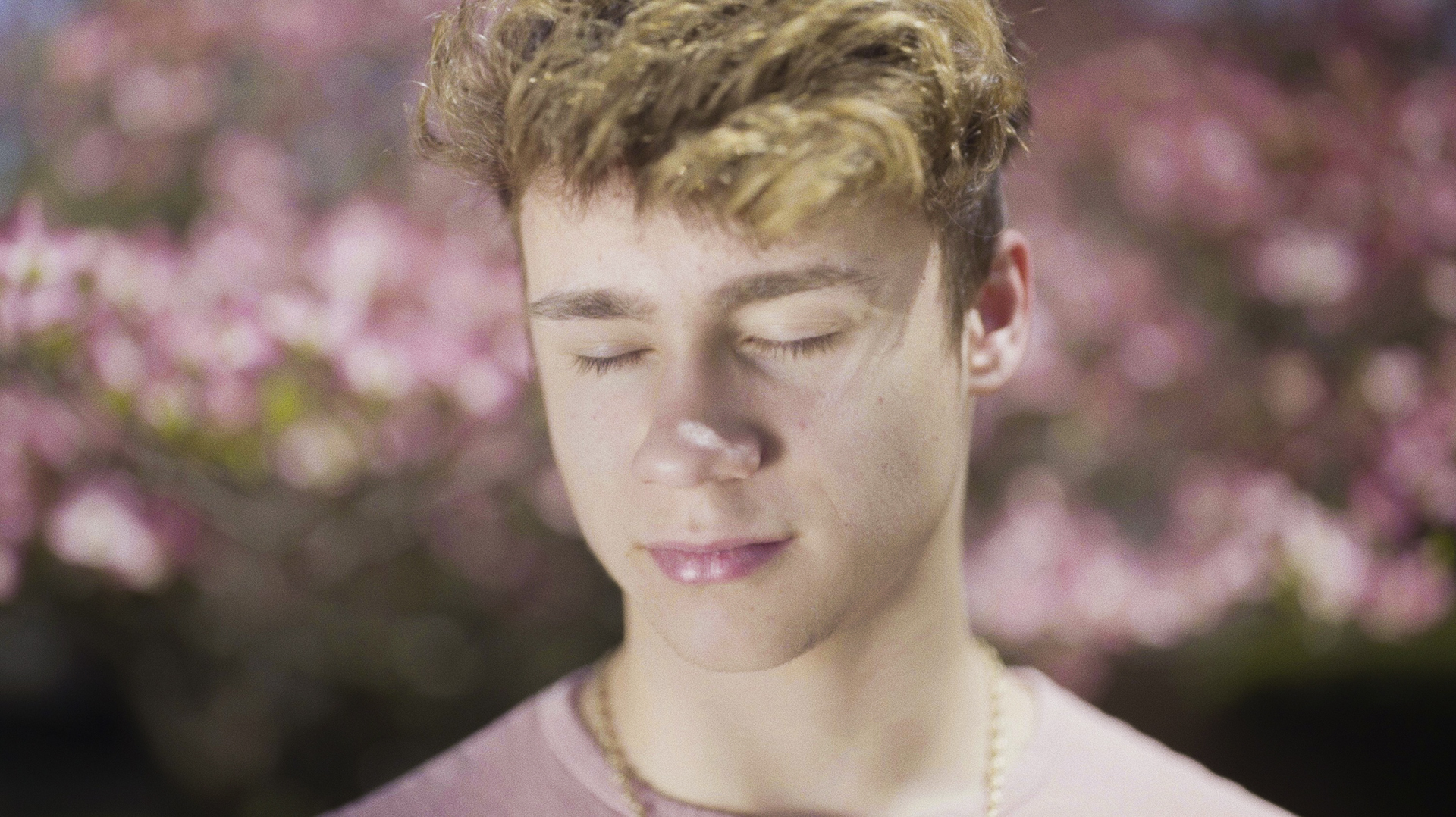

The documentary Jawline observes the life of Austyn Tester, a teenage broadcaster on the platform YouNow who is trying to find success online with the hopes of escaping the limited prospects of his life in rural Tennessee. The film, which premiered at Sundance and will hit theaters and stream on Hulu starting Aug. 23, is the debut feature of director Liza Mandelup, who follows the then-16-year-old as he attempted to make it in the over-saturated industry of social media influencers, banking on his brand of positivity and an earnest belief in his dreams.

As Tester interacts with fangirls who crowd around him at a mall meet-and-greet and later fails to catch hold in the mainstream, Mandelup shows the lengths and limits of finding fame through these new channels. In a conversation with TIME, Mandelup talked about what fascinated her about the world of influencers and the voices she tried to center in the film.

What brought you to the subject of teenage influencers, and broadcasters in particular, for your first film?

The emotions I felt during my teenage years felt so extreme when compared with my life now on a daily basis. I thought, that must be so different today, with so much technology and having social media be an extension of yourself. There’s a new landscape that exists about what it means to be a teenager in our modern times. As I started researching this, I found the world of meet-and-greets and it was like a snowball effect—I saw that world come together online. After that, it was, what angle do I need and how do I find a main character I could connect with on a human level?

Is that how you felt about Austyn amid that crowded field of broadcasters?

When we filmed with Austyn, there was something about him that made me feel it could be a more cinematic film, because of how much of a dreamer he was. He had these fantasies. He had a very naive perspective. That felt different to me—where a lot of the other boys had managers and knew the ins and outs of this world, Austyn was very far from that. He represented the new American dream to me: get out of your factory town through chasing your dreams on social media.

You got Austyn and his family to talk about really vulnerable things, like living through poverty and abuse. How did you earn and maintain that trust?

The whole crew and I have a very casual nature to us that works in our favor. It’s not like we show up to shoot and get in and get out. We hung out there all day. I have this approach to working with a subject that’s like, I’ve got nowhere to be except hanging out with you. I’m like a friend trying to talk to you about what’s going on in your life, not treating you like you’re someone I don’t get. I came to that from my own life. When I was a teen, I loved putting myself in situations where I’d wander around, talk to people, go to parties where I didn’t know anyone or make friends randomly in the store.

You really center the voices of teenage girls in the film. Why were they an important part of this narrative?

I met these girls and I was like, I know exactly how you feel. I remember feeling as a teenager that nobody cared about me, nobody was listening to me and nobody was taking me seriously.

I wanted someone to be concerned about how I was feeling and to stop me and say, “Are you OK?” or “I care about you.” I wanted that from peers—it wasn’t a parental thing. The girls were channeling those emotions to these boys, because they couldn’t find it in school. But these boys were simulating a person who cared—that person you wish you knew in school that tells you you look pretty with no makeup on, and asks how your day was and asks if you had a good day in school or if you’re feeling OK. We don’t take seriously how teenage girls feel and it leaves them to figure out for themselves what to do with that emotion.

The girls who flock to Austyn talk about being bullied and having hard home lives. Austyn grew up in a similar situation. How did you see that connection come into play when he interacted with his fans?

I always felt like it was this world of escapists, finding each other. That’s the heart and soul of the community, that they’d all been through something. They didn’t have everything they needed, whether that’s financial, social, emotional, family—whatever it is.

What did you take away from making this film when it comes to what youth culture means now and what we, as adults, should be doing for kids?

Teenagers are the same, emotionally. They crave the same things as they did before. They’re just finding expression in different ways now and in ways you should be aware of. I don’t like when people are like, “I’m so old. I don’t understand that world.” Take the time to understand it so you don’t isolate teens in that sense. That’s how I was able to connect with everyone in that world as an outsider. I was genuinely trying to understand it. I could tap into my own teen years and try to relate to them.

With Austyn, specifically, what did you learn about the costs of vying for online fame? For him, it didn’t end up working out.

Where we’re at right now with getting big online, it’s a bit of an illusion. Austyn’s story is about that personal cost and the illusion that a teenager from the middle of nowhere with no background to support him in this can give it his all and make it on social media. It seems like anything is possible with social media, but it’s a very oversaturated industry. And maybe Austyn could have had millions of followers, but would that last and do anything for him in the long term?

The movie also shows the effects of poverty in America in the lack of options people have and what they’ll do to get out of their situations. How did you think about the socioeconomic issues that came up in the story?

I wasn’t looking for that, but it’s a world of people looking for upward mobility and looking to change their status and escaping what’s going on in their life. A byproduct of that is having a lot of people with financial struggles. It was something I discovered along the way and incorporated into the story. And even when we met Austyn, I didn’t know his situation. I was hesitant to even include it because that’s not why I was there, but it has impacted his life so I had to.

The moment that stood out to me was when he came back from the tour and realized that his life back home was still the same.

It was surprising for us, too. We went back to that shoot thinking we were going to document a hometown celebrity. And he went back to his life just like nothing had changed. It is sad. To say you failed at something is hard. You’ve failed at things, I’ve failed at things, but to experience someone’s failure with them is really hard.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- L.A. Fires Show Reality of 1.5°C of Warming

- Home Losses From L.A. Fires Hasten ‘An Uninsurable Future’

- The Women Refusing to Participate in Trump’s Economy

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- How to Dress Warmly for Cold Weather

- We’re Lucky to Have Been Alive in the Age of David Lynch

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Column: No One Won The War in Gaza

Write to Mahita Gajanan at mahita.gajanan@time.com