Mikhail Gorbachev, the first and only President of the Soviet Union, has died, according to Russian media. He was 91.

He will be remembered, at least in the West, as a pragmatic leader who transparently transitioned the Soviet Union away from its days as an Evil Empire and toward a more modernized economy that was integrated on a global scale.

At home, however, he is largely seen as the man who brought a collapse of Soviet-era prestige and power, preaching reform while protecting his own influence. In a 2017 poll of Russians, 30% said they had anger or distaste toward him, and 13% said they felt disgust or hate for him. For many, he was the harbinger of the end of Russian greatness.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which has led to punishing economic sanctions and the highest tensions with the U.S. and Europe since the Cold War, has been seen as an attempt to reclaim at least some of the power and glory lost as a result of Gorbachev’s legacy.

Gorbachev himself refrained from commenting publicly on the war, but argued in 2016 that tensions were the fault of Kyiv’s lean toward NATO. “This conflict was not of Russia’s making. It has its roots within Ukraine itself,” Gorbachev argued.

When he left office in late 1991, there was no guide for what he should do next.

The three most recent leaders of the Soviet system had died in office, and the most recent to have left the office with his health, Nikita Khrushchev, had died 20 years earlier. They offered few lessons on what, exactly, a former absolute leader of the Soviet system could do in retirement.

The leader of the new Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, had made clear his disdain for Gorbachev, standing him up for a meeting, commandeering his offices to down whiskey before 9 a.m. and rushing Gorbachev from his Kremlin apartment in a manner that, according Gorbachev’s 1995 memoirs, “were most uncivilized, in the worst inherited Soviet traditions.” Yeltsin wouldn’t even meet him to hand-off the nuclear codes. (“I should have sent him off somewhere,” Gorbachev would tell an interviewer during a 2019 documentary.)

So at age 60, the ruler of a collapsing Super Power found himself out in the Russian cold. The Russian public dismissed him as a fool who embodied a failed experiment with communism and a worse-imagined pursuit of reform. The country quickly went to work burying its past, voting to rename Leningrad as Saint Petersburg in one of the most high-profile attempts at historical revision. To foster a sense of national identity, the country would also start to revive the pageantry from its czarist era, including its national anthem.

In the years that followed, Gorbachev would emerge in the West as a global figure who presided over what was, at the time, seen as a peaceful end to the Cold War. He started what is commonly called the Gorbachev Foundation to publish documents related to the period of perestroika that he presided over and his approaches to policy. He became something of a celebrity as well, charging hefty fees for speeches. He wrote a monthly column on global affairs for The New York Times and also appeared in Pizza Hut commercials, a nod to just how closely the world watched the collapse of an empire that spanned 11 time zones.

“Change is rarely painless,” Gorbachev wrote in his 2016 memoirs. “It affects people’s lives and interests, and that is why we need to do everything possible to mitigate painful consequences. There should be no attempt to go for a ‘big bang’ at the outset.”

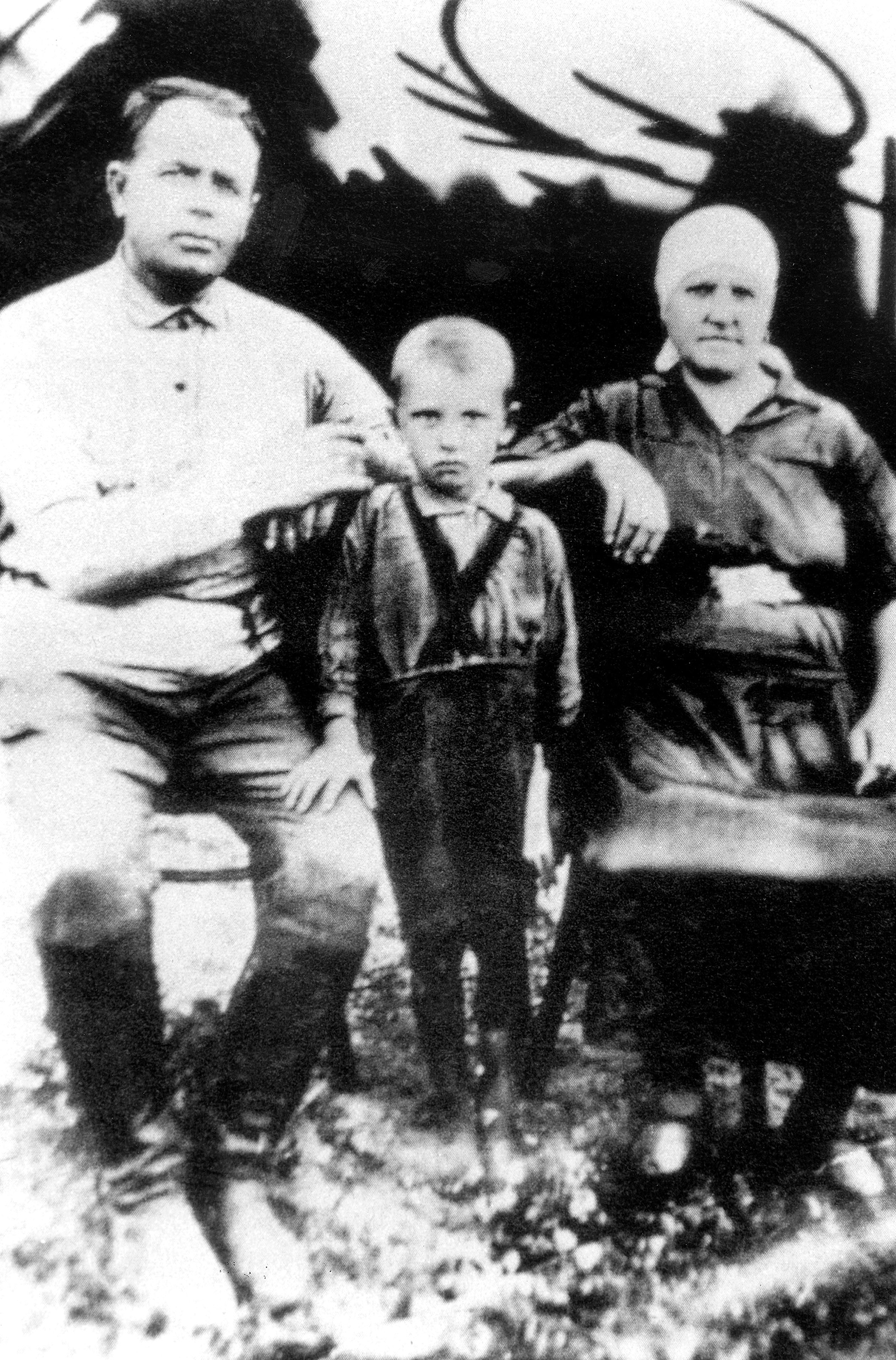

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was born to a peasant family in Privolnoye, a small village some 800 miles south of Moscow, on March 2, 1931. Josef Stalin was leading the country through very dark days of under-performing harvests and brutal authoritarianism; resources were so scarce, some types of theft were a capital crime. Two uncles and an aunt died during a famine that Stalin orchestrated to punish the peasants, and both of his grandfathers were sent to the Gulag labor camps where at least one was tortured. World War II began in 1939 and German forces occupied Privolnoye in 1942. “Here were my roots; this was my homeland. I was bound to its earth, its lifeblood ran in my veins,” Gorbachev would later write.

As a teenager, Gorbachev joined the youth wing of the Communist Party, which was the lone political party of the Soviet Union. His biography seemed taken directly from the best of Soviet propaganda. He excelled in school and his essay “Stalin Is Our Wartime Glory, Stalin Gives Flight to Our Youth” was held up as a model of Communist patriotism. In 1948, Gorbachev received the Order of the Red Banner of Labor prize for his sometimes 20-hour days in the farm fields during summer breaks from his studies. That honor earned him admission without so much as the indignity of an entrance exam to study law at Moscow State University. There, he met Raisa Titarenko, a young Ukrainian woman who would become his wife and unrivaled adviser, as well as Czech student Zdenek Mlynar, who would be the ideological champion behind the liberalization-minded Prague Spring in 1968.

“Members of Gorbachev’s generation emerged from the dreadful war with optimism and a fierce determination to improve their lives,” historian William Taubman wrote of that era. But they were still operating inside the Stalinist system, which meant no open dissent or criticism of the power structure. Recognizing this, Gorbachev continued to ingratiate himself with the Communist Party, becoming a full member at age 21 and setting in motion a career in politics that was marked by careful risk assessment.

Stalin’s death in 1953 and the resulting de-Stalinization of the Soviet Union provided an opening for Gorbachev. He aggressively embraced Khruschev’s reformist agenda — although, to be clear, it was a reform program for the Communist Party as the lone source of power in a sprawling empire — and Gorbachev began the slow and steady climb to the party’s upper ranks, always in the mix but never responsible for anything that could haunt him later. Finally, in 1985, he had reached the apex of the Soviet system and started what he saw as a last-ditch attempt to save it from itself.

“I could not imagine how immense were our problems and difficulties,” he said in 1991, accepting a Nobel Peace Prize. “I believe no one at that time could foresee or predict them.”

Gorbachev did not pretend his country was without need for change. But once Gorbachev started pulling at the thread of the fraying Soviet scarf, it untangled rapidly and violently. Stalinist communism overlaid on central European cultures was proven incompatible when offered autonomy. Capitalism triumphed over centrally planned economies. (So, too, did corruption and cronyism.) Engagement was more alluring than isolationism. Lithuania broke away from the Soviet Union in March of 1990, followed quickly by Estonia and Latvia. By the end of 1991, 10 Soviet republics would declare their independence. Gorbachev, former spokesman Andrei Grachev would write in 2008, saw the system “as an annoying impediment to the great reform.”

In the West, observers saw potential. He was a particularly fond figure for George H.W. Bush, a former U.S. Vice President and President. TIME named Gorbachev the “Man of the Decade” at the end of the 1980s, shortly after the first parts of the Berlin Wall fell. When told of this honor, Gorbachev told aides this magazine was missing the point. “It’s not about me,” he said, according to a Politburo transcript, “the scale of our design is global.”

At home, his people — at all levels — held hope and skepticism in equal measure. The party’s Politburo was frustrated with Gorbachev’s uneven pace and perhaps outsized expectations. The rank-and-file Russians were not feeling the promised reforms and grumbled that, at least under the old regimes, they expected to be hungry. Now? Unrealized hope had made the Russians angry. “It was inevitable that the country’s workers would eventually take advantage of the new freedoms Gorbachev had offered,” longtime Washington Post journalist Robert G. Kaiser wrote in 1991.

But Gorbachev ultimately was unable to create a durable system of his own. As he was pursuing reforms and fighting to hold onto power, Gorbachev’s inner-circle conspired against him, leading a three-day coup in 1991 that left Gorbachev effectively under house arrest at his dacha in Crimea. The West sought to keep him in power and the Soviet Union functioning and reforming; it obviously did not work. As Gorbachev would tell Yeltsin in 1991, “if we want democracy and reforms we must act according to democratic rules.” For Gorbachev, that meant watching the Soviet hammer-and-sickle-and-star flag be lowered over the Kremlin and be replaced with the tricolor Russian flag.

In the intervening years, Gorbachev sought to tell his versions of what unfolded at the end of the Soviet Union. Still, reforms like those begun under Gorbachev take time and he provided a useful scapegoat for the gap between promise and reality. Yeltsin initially supported a post-presidency, Gorbachev-led think tank only to have that support withdrawn. Gorbachev gave a speech to the U.S. Congress in 1992, warning that the post-Cold War environment was uncertain at best. Writing in his 1995 memoirs, Gorbachev said he was under surveillance and denied any inclusion in the new country’s foreign policy.

In Vladimir Putin-era Russia, Gorbachev sought to walk a careful line between pushing reform and keeping his foundation on the right side of the regime. Writing in 2016, Gorbachev deftly noted that “there is again a great sense in Russia of a need for change” amid a slide back to authoritarianism. Still, he sided with Moscow as tensions rose with Ukraine.

The Soviet Union is gone, but Gorbachev never was quite able to completely break with the Soviet mentality itself. Even out of power almost three decades, there was still a temptation to defend Russia’s imperial history, perpetrated through the twentieth century by a system mastered by Gorbachev. Ultimately, it took a child born to a family persecuted by Stalin to turn the political power inward to destroy that system.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com