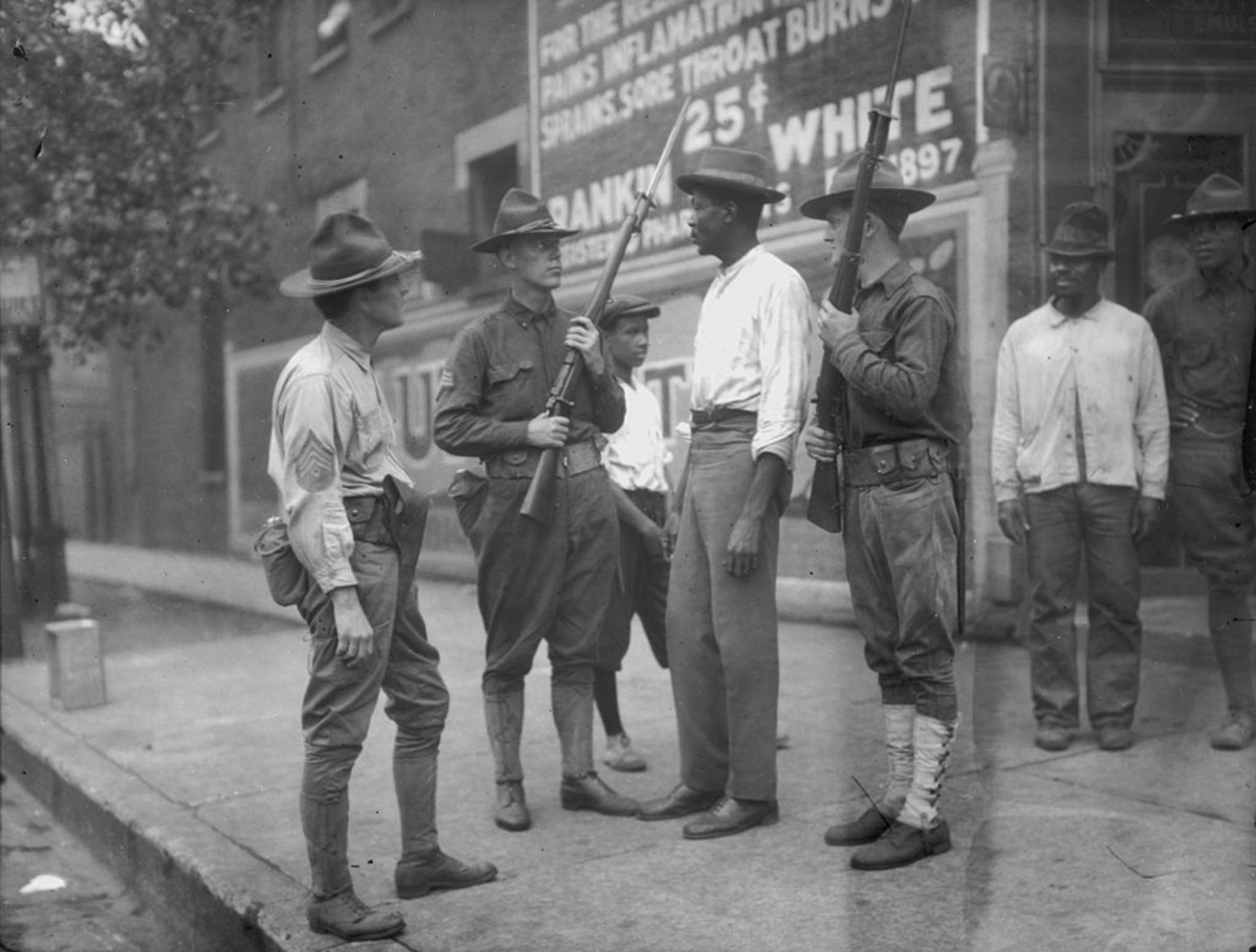

As Chicago on Monday marked the 100th anniversary of a week of violence there, Mayor Lori Lightfoot reminded her audience that the events of July 27-Aug. 3, 1919, reached far beyond that city and those days. Rather, they marked the peak of a wave of anti-black violence that roiled the United States in 1919. The season would come to be known as the “Red Summer,” a name coined by NAACP field secretary James Weldon Johnson to acknowledge the blood that was shed.

“The story of Red Summer is a story of a nation fraught from the clash between hope and threat, between the tension of new dreams encountering entangled fears — all rising until it finally exploded,” Lightfoot said Monday at a ceremony to mark the centennial. “Though we are gathered here to commemorate the events of 1919, it is the consequences of those very active forces that we are still reckoning with a century later. From the vantage point of 100 years ago, we can see our past has been present in both our capacity to overcome its brutal legacy and how we continue to struggle under its weight…learning from our history is also possible only by knowing our history.”

During that season, there were at least 25 major riots and mob actions across the country, according to Cameron McWhirter’s Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. Hundreds of people, most of them black, were killed, and thousands were injured and forced to flee their homes. McWhirter spoke to TIME about the history of the Red Summer and the forces that sparked the race riots in Chicago and across the country.

TIME: What was going on in the United States and the world that created the factors behind the Red Summer if 1919?

MCWHIRTER: Nineteen-nineteen was a period of great anxiety. The economy was topsy-turvy. Inflation was out of control. There were an enormous amount of strikes. The Bolsheviks had taken over the Soviet Union, and communists and anarchists were agitating all over the world. The Red Scare was underway. Black equality and black assertions of rights were being equated with some sort of radical action and radical message, but the link between African-American efforts to achieve full rights in America and communism were pretty non-existent at the time.

And then there were three main things were happening in 1919:

African-American soldiers had served in World War I in huge numbers. That was very empowering. And when they come back and they’re walking down the streets of the southern towns they had left just a year or two earlier, they’re being spit on.

African Americans moved north to the cities during the Great Migration — New York, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland — [where] they were a little freer. They were paid better. In Chicago they had a certain amount of political power. This new freedom caused a lot of anxiety among ethnic groups that were competing for the same kind of jobs. Many unions were prejudiced against letting in black people.

Thirdly, a big factor was sharecroppers. African-American cotton growers were actually making money in 1919 because there was a huge worldwide demand for cotton for textiles. Everyone needed clothing after the war. They were buying houses, cars, land. Small southern white towns suddenly felt threatened.

What were the most important moments of the Red Summer?

My book starts in April, when Carswell Grove Baptist Church, a sharecroppers’ church, is burned down in rural Georgia. In May there’s a gathering in New York where the NAACP and others to try to talk about federal lynching legislation. There’s a big riot in Charleston [May 10-11]. There’s a terrible lynching in Ellisville, Miss. [June 26]. And it just goes on and on. Chicago was the pinnacle. Washington, D.C. is right before [July 19-24]. [Riots break out] in Knoxville, Tenn. [Aug. 30-31] and Omaha, Nebraska, [in September 28-29].

One story about Omaha: A black man was accused of attacking a white woman, and then the man was arrested and brought to the courthouse. A mob surrounded the courthouse demanding he be turned over or they’d kill him. The white progressive mayor came down and said we’re not going to turn this man over. The mob knocked him down and tried to kill him. He got away just by the skin of his teeth. The mob eventually broke in and dragged the man out and murdered him. There are horrific pictures of that. Another man who worked in an office nearby brought his young son to witness it, and said, I want you to see this. This is what people can do to each other. The kid who was crying as he watched this was Henry Fonda, the actor. I would argue it changed his view of race relations forever.

How did the press cover the riots?

[The writer and poet] Carl Sandburg wrote prescient articles about trouble in Chicago just before the riots erupted. If an African-American family tried to move outside the black neighborhood, people would leave a bomb at their doorstep. Unfortunately some of the papers would say blacks were rioting and report that anarchists were allegedly operating in the black neighborhoods, but there is not real evidence of any of that. These actions were overwhelmingly by white mobs.

Every time these things started happening, there would be screaming headlines “riot in x city.” That happened over and over again. It became this panic across the country where everyone is like, “Where’s the next race riot going to happen?”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

How did the Red Summer come to an end?

There were lots of governments that didn’t want to look at what had happened, that delayed taking action because they didn’t want to admit that they couldn’t handle the situation, until eventually they had to call in troops. With mobs if you don’t act quickly, then you’re in big trouble really fast. And that was the message of that whole summer. Eventually governments started to figure out that whatever their position on racial equality is, a massive riot isn’t good for business, so they started to act very quickly when stuff started to erupt, and then [the Red Summer] sort of just ran out of gas.

What’s the legacy of the Red Summer? How does it tie into the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s?

It was the beginning of this long process of arguing to the federal government that it needed to intervene. The NAACP dramatically expanded that year, and they fought in the courts [and] started building coalitions in Congress with mostly Republican Senators and some congressmen to really fight for federal laws to protect people from extrajudicial action by mobs. (They were pushing for a federal lynching law, which did not pass.) African Americans were also building consensus through newspapers and magazines like The Crisis; they were developing art and the Harlem Renaissance comes after all of this.

The simple message of 1919 by the NAACP was, ‘We’re American citizens. You don’t have to like us, but you have to give us the same rights as everyone else.’ That was considered, by many, to be a radical message. There are points where I’m reading James Weldon Johnson in 1919, and he sounds like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Those problems were articulated at that point: We want to vote like everyone else, eat where we want to eat, live where we want to live, have the same legal rights in the courts. On a huge scale, that fight started in 1919.

Are there any remaining mysteries of that period?

I don’t know whether we’ll ever know a lot of things, but one thing that really jumps out to me is the killings in Elaine, Ark. [Sep. 30-Oct. 1], where a white mob goes after sharecroppers. We don’t know how many people were killed there. We’ll never know. They just went off into the fields and started shooting people. There’s no government investigation of it. Now some people are trying to figure out, through death records, who was killed, but it’s very complicated work, and I don’t think we’ll ever really know exactly how many people died.

Why aren’t these events better known?

There were a bunch of reasons. One guy wrote a book shortly after the riots and he said basically it was so horrific that people tried to forget it. I found that to be true in the small town in rural Georgia where Carswell Grove Baptist Church burned down. Ninety-plus years later, people were reluctant to talk about it. White people certainly didn’t want to talk about it. In the last five, six or seven years, and now at the centennial, people are talking more about them. Charlottesville, Ferguson — [these events] really need to be put into context.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com