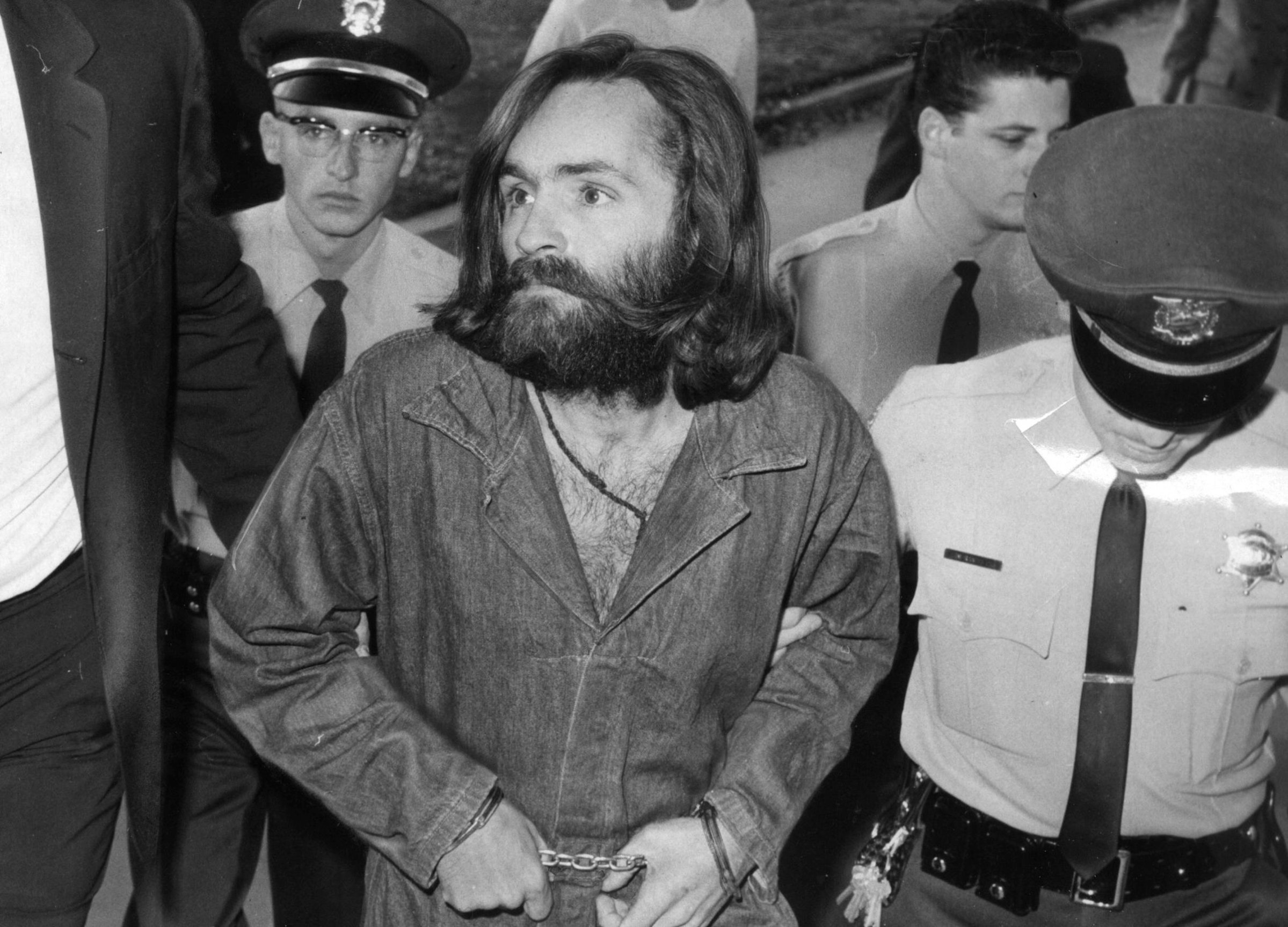

In Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, one of the most infamous crimes of the 20th century plays a prominent role: though the movie’s story is fictionalized, Margot Robbie plays Sharon Tate, the real actor who was a victim of the 1969 murders committed by followers of the cult leader Charles Manson.

A half-century after Tate’s death, there remain plenty of myths and theories about why Manson’s followers carried out the murders — and one of the biggest questions is the extent to which Charles Manson himself was involved, and why.

At the time, prosecutors said that Manson, who wanted to be a rock star, ordered the murders of Tate and four others because the previous owner of the house at which the deaths occurred — Terry Melcher, a music producer — had refused to make a record with Manson. Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi also argued that Manson was obsessed with the Beatles’ White Album, and thought its message was that he should start a race war by framing black innocents for crimes against affluent white people; the “race war” was nicknamed “Helter Skelter” after that song, and the fact that the word “pig” was written on the wall at the crime scene in blood was linked to the track “Piggies.”

But, says James Buddy Day, a true-crime TV producer and author of the new book Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson, everyone involved in the crimes had a slightly different take on what happened. While researching the book, Day conducted interviews with Manson — who was still serving a life sentence — during the year leading up to Manson’s death on Nov. 19, 2017, at the age of 83, and is thus believed to be the last person to interview the infamous criminal at length.

“There are so many people involved in the Manson story, not one of them can say what really happened. No one was making decisions for the whole group,” he says.

One of the people who offered Day a version of the story was, of course, Manson, who maintained his innocence until his death. “I didn’t have nothing to do with killing those people,” he told Day in a phone call. “They knew I didn’t have anything to do with it.” So the story Manson told Day about the summer of 1969 is one in which, unlike in the “Helter Skelter” story, his role in the murders is relatively small.

“There’s this whole underlying story people don’t know,” says Day, who, 50 years later, hopes to set the record straight. The theory that Day describes in his book revolves around events that were known 50 years ago, but are not as well known today as the Tate murder is. Rather than looking at grudges or hidden messages, this story starts instead with a botched drug deal that took place that July 1.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

The story, as Day tells it in his book, is this: Charles “Tex” Watson was a drug dealer in Los Angeles who lived at Spahn Ranch with Manson and his followers. Watson had stolen money from another dealer, Bernard Crowe. Crowe called Spahn ranch to look for Watson. Charles Manson was put on the line, and Crowe threatened to come kill everyone unless he got his money back. The threat led Manson to go to Crowe’s Hollywood apartment. The two men fought and Manson shot Crowe in the stomach; Manson believed he’d killed Crowe, though he hadn’t.

Day identifies this moment as a turning point. After, as fear of outsiders and retaliation intensified, Manson warned the ranch residents that the Black Panthers — a group to which he believed Crowe belonged — were going to come after them.

“Manson said, ‘Now we gotta fend for ourselves because the Black Panthers are going to kill us,'” says Day. “At that point, Manson has two problems: First, he’s worried that Black Panthers will take revenge for the drug dealer he believes he’s murdered, and second is that anyone in the group can rat him out. So he comes up with a strategy of saying, if everyone’s willing to commit these violent acts, it will bond us together, and no one can tell on anyone.”

The dynamic of the group further changed, this theory alleges, when Manson invited the motorcycle gang known as the Straight Satans to live on the ranch, to enjoy the female company in exchange for protecting the rest of the group from the Black Panthers. The Straight Satans weren’t the only ones he invited to the ranch for that reason. Another man who came around that time was Bobby Beausoleil, a wannabe biker he’d met via the Topanga Canyon music scene.

Beausoleil told Day that he wanted to impress the Straight Satans, so when they wanted drugs, he volunteered to find some. He got them some mescaline he’d purchased from his friend Gary Hinman, a grad student at UCLA. After the Straight Satans complained that the drugs were bad, Beausoleil tried to get their money back; on July 25, he and Hinman fought and both were injured. Manson was called, and came over with reinforcements. He slashed Hinman’s face with a Confederate sword and fled the scene. Worried that Hinman would call the police, Beausoleil stabbed him to death on July 27.

He then tried to cover his tracks: Beausoleil wrote “Political Piggy” on a wall in blood and later told the police that he had seen the two men who killed Hinman, and that they were black. Mary Brunner, another former Manson family member, told the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Dept. in Dec. 1969 that Beausoleil also drew a black cat paw print on the wall to suggest the Black Panthers had been responsible for the crime.

“I don’t remember a lot of what happened immediately after I killed Gary,” Beausoleil told Day during conversations on the phone from prison. (Beausoleil, who has admitted to the murder, was tried twice and convicted the second time.) “There was a concerted effort to throw off the police and make it look like someone else had done it.”

When Beausoleil was arrested on Aug. 6 outside L.A., Manson worried he might spill the beans about the framed crime scene or what had happened with Bernard Crowe. Manson told Watson to figure out a way to keep things quiet.

Someone at the ranch hatched a plan to replicate a copycat crime scene elsewhere, so police would believe Beausoleil’s story that Hinman’s killer was still on the loose. A spot was chosen: a house on Cielo Drive, apparently one that Watson knew because he had gone to a party Melcher threw there. On Aug. 8, Watson and three female members of the so-called Manson family — Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel and Linda Kasabian — headed to the house. Five people were murdered there: Tate, the three people she was hanging out with, and a man who ran into them after visiting the caretaker of the property. “PIG” was written in blood on a wall. The gun Manson used to shoot Crowe was the same gun Watson used that night.

On Aug. 10, they struck again, this time with Manson joining the group at the home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. Watson stabbed Leno, and he, Krenwinkel and another Manson family member named Leslie Van Houten stabbed Rosemary. Day’s theory is that Manson may have wanted money from Leno, a grocery-store-chain owner who liked to gamble, to pay off the Straight Satans, who were still angry about getting their money back for the bad mescaline.

A few months after Tate’s body was found on Aug. 9, 1969, Charles Manson and several of his followers were arrested for suspected auto theft. One of the Manson family members involved, Susan Atkins, told her cellmates that theft was not the limit of their crimes, and that confession led authorities to connect the group to the murders.

So, while media outlets like TIME reported that Manson had ordered the murders, which was also the timeline that came out in the trial, Manson’s own version was that his followers orchestrated the whole thing, and he was only involved in a passive way.

On Jan. 25, 1971, Manson, Susan Atkins, Patricia Krenwinkel, and Leslie Van Houten were convicted. They were later sentenced to death, but those sentences were changed to life in prison after California temporarily banned the death penalty in 1972. Later that year, Watson was convicted of the Tate murders, and Manson was also convicted of the murders of Gary Hinman and Donald Shea, a Hollywood stuntman who was killed at Spahn Ranch in late August of 1969. The lead prosecutor, Vincent Bugliosi, wrote a 1974 bestseller, and died in 2015. Linda Kasabian was granted immunity for giving testimony. Watson, Beausoleil and Van Houten are still alive and in prison. And there are several other Manson family members who were not involved in the Tate-LaBianca murders, but have talked to the press and done documentaries about life on the ranch, including the upcoming one Day is executive producing, Manson: The Women.

So with all that time talking to Charles Manson, what does Day believe actually happened? He says he thinks Manson’s version is more likely than not pretty close to the truth, but he doesn’t agree with the cult leader’s feeling that the drug-deal story is exculpatory.

“I think there’s no question Manson is culpable for those murders, if not all of them,” Day says he believes. “The murders would not have happened without him.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com