The man known for his flamboyant headgear and his public boasts about sleeping with other men’s wives was an unlikely candidate for political office. He dismissed his critics as vermin, insisting that only he could set the record straight. He brushed off people who mocked his lapses in grammar and spelling, then wrote a best-selling autobiography, using collaborators to help with the pesky grammar and spelling issues. He claimed to be taller and thinner than he actually was. He bragged about taking women by storm, but issued denials when accused of sexual misbehavior. He crowed about how much money he made, even though his risky financial ventures often failed. He conceded that he knew nothing about government but ran for national office anyway, to spite someone who had joked that he could never be elected. When he did win, he boasted obsessively about how many votes he’d gotten and how little money he’d spent obtaining them, thanks to his knack for connecting with crowds. His provocative crudeness made him especially popular with white Americans who felt alienated from the country’s East Coast elites. Over time, he came to be associated with racial slurs against immigrants, African Americans, Native Americans and Mexicans and his name became a rallying cry for jingoistic nationalism, misogyny and white supremacy.

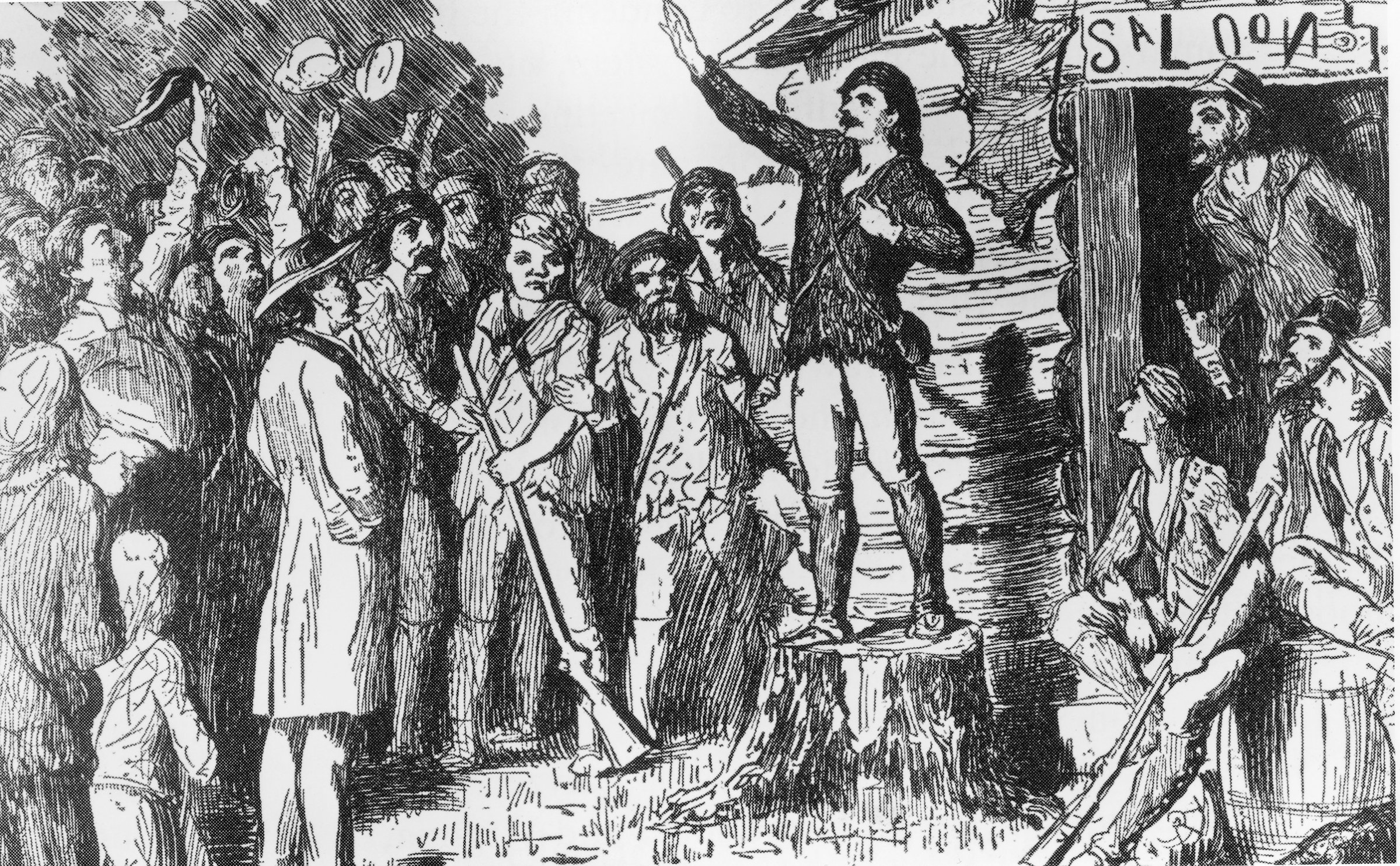

I refer, of course, to Davy Crockett (1786–1836), whose career in many ways anticipates that of 21st century celebrity politician Donald Trump. Important differences distinguish the two men: Crockett did actual military service, for one; he was not born into wealth, for another. And though Crockett waged war against Native Americans, he also broke with his party by voting against President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Both Crockett and Trump, however, understood celebrity. The new media of the 1820s and 1830s helped Crockett rise to fame and political power. Engravers and printers reproduced his portraits; publishers used his name to sell almanacs; actors made a fortune impersonating him onstage.

Almost two hundred years later, tabloid journalism, reality television and Twitter similarly boosted Trump. Reporters latched onto both men because their showmanship made for good copy. Like most successful celebrities, Crockett and Trump understood how to leverage tensions between their supporters and representatives of the media. Both favored direct appeals to the public and both often dismissed what others printed about them as lies.

The similarities between Donald Trump’s and Davy Crockett’s celebrity exist because the Internet did not invent celebrity culture and because Hollywood did not create the star system. Twenty-first-century social media platforms and 20th century entertainment industries simply capitalized on a much older phenomenon spawned by a nexus of popular journalism, commercial photography and newly rapid forms of travel.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Yes, celebrity culture has changed over the last 200 years. The theatrical culture that in the 19th century gave rise to the first global celebrities distributed autonomy and influence fairly evenly among actors, audiences, playwrights and critics. The Hollywood studio system shifted the balance of power by concentrating control in studio heads. How we gender and value celebrity has shifted. In the 19th century, the typical celebrity was a mature man venerated for his professional accomplishments. By the early 21st century, the typical celebrity was a young woman judged primarily on her appearance and likely to find her success derided and dismissed even when it was the result of exceptional talent. Technological changes have also had real effects, though many Internet platforms merely allow people to combine activities that used to be separate, such as pasting images into scrapbooks or sending fan mail.

Celebrity culture, whether A-list or Z-list, Bollywood or Hollywood, consists of interactions between celebrities, media and publics. Each has partial, contested, but real agency, and each uses that agency to collaborate and tussle with the others. The energy expended in these skirmishes and alliances drives celebrity culture. Celebrities might try to undercut the media, as the 18th century English actor David Garrick did when he responded to hostile reviewers by publishing his own anonymous rebuttals of their critiques. They might try to use media to reach the public, as Sarah Bernhardt did when she wrote letters to newspaper editors that, once published, would influence newspaper readers. Or they might turn media workers into allies, as Hollywood star Constance Bennett did when she cultivated reporters whose positive articles improved her standing with the public.

Celebrity culture’s triangular structure has proven durable precisely because it is so flexible. When norms change and new media take off, publics may temporarily find themselves more influential, stars may briefly acquire more clout, media companies may momentarily seize the upper hand. But such shifts do not magically transform a three-way drama into a monologue. Celebrity culture exists only when publics, media producers and well-known individuals engage with one another. If one group were to drop out or ignore the others, celebrity and fandom would disappear.

As soon as Donald Trump was elected president, commentators began to argue that the rise of mass media was responsible for his victory. But every U.S. president, from Abraham Lincoln to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, has been what The New Yorker’s Alex Ross called Trump in one such piece: “as much a pop-culture phenomenon” as a “political one.”

The history and theory of celebrity teach us that we get the celebrities we deserve. Capitalism does not foist any particular celebrity on us, even if capitalist ideology finds many affinities with celebrity culture’s exaltation of individuals. Ever since the 1830s, when the commercial press first helped give rise to modern celebrity culture, the journalistic landscape has been too fractured and chaotic for the press alone to manufacture celebrities. Publics have proven difficult to influence. Even concerted publicity campaigns can fail, and reporters can be surprisingly hostile to the most popular entertainers, from Byron to the Beatles. Conversely, publics alone cannot a celebrity make, because their access to celebrities is always mediated by photographers, journalists, film producers, disc jockeys, concert bookers, software developers and celebrities themselves. Though stars are never self-anointed, many play a key role in crafting their personae. If nothing else, most stars possess a shrewd grasp of how to manage the media and attract public attention.

In some instances, celebrity culture can turn out better than its harshest critics could ever imagine; in others, it descends to lows that even the grimmest dystopian would fail to predict. Sometimes cause for joy, sometimes for despair, celebrity culture is neither panacea nor plague; it is what all the groups whose interactions create celebrity culture make of it.

As a result, even those who ignore celebrity culture are implicated in its travails—not because society demands that everyone stay on top of the latest celebrity gossip, but because failing to pay attention to this particular status system can have consequences for society at large. Celebrity culture is always a debate about whom and what we value. The slightest interventions can matter in contests for agency where no single person or force can ever be assured of permanent victory. Precisely because no one group or individual controls the drama of celebrity, each of us has a limited but real role to play in shaping the course it takes.

Adapted from The Drama of Celebrity by Sharon Marcus. Copyright 2019 by Sharon Marcus. Published and reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com