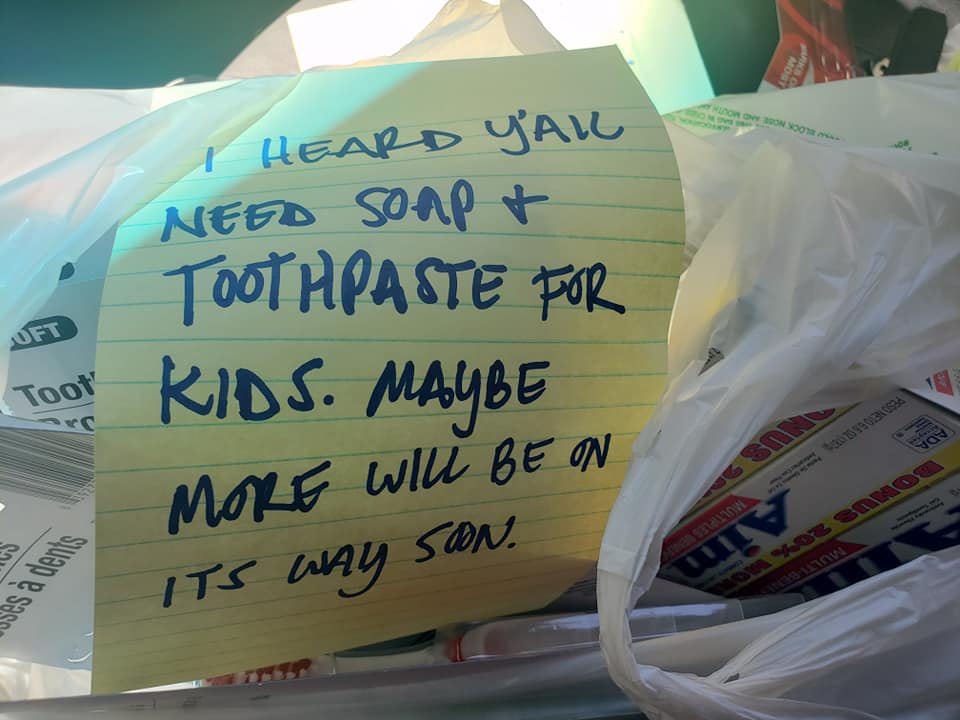

Gabriel Acuña, 41, drove to the Clint, Texas Border Patrol facility on Sunday afternoon to donate toothpaste, toothbrushes, soap and baby shampoo to the nearly 300 migrant children housed inside at the time. He left the supplies in a plastic Dollar Tree bag at the door of the facility with a note —”I heard y’all need soap and toothpaste for kids. Maybe more will be on its way soon.”

The same day, a group of six people attempted to donate about $340-worth of supplies, but found the facility locked, including the front lobby. Members of the group tell TIME they were ignored by personnel moving in and out of the gated facility. The donors said they returned on Monday afternoon, and were ignored again.

The Clint facility, about 20 miles southeast of El Paso, has been criticized nationally for the inhumane and unsanitary conditions reported by attorneys who have visited it. But it is not accepting donations, and neither are any of the other Customs and Border Protection (CBP) facilities across the country. Details shared by attorneys who toured the Clint facility included children sleeping on concrete, being fed inadequately, going without basic sanitation and older children caring for younger children. In court on June 18, a Justice Department attorney argued that toothbrushes and soap may not be necessary for providing safe and sanitary conditions for shorter stays, sparking national outcry.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to requests for comment before publication, but a transcript of a Tuesday conference call between a CBP official from the Public Affairs office and reporters indicates that it is working with the Office of Chief Council to learn how to legally accept donations. The copy of the transcript was sent to TIME by the CBP Public Affairs office.

“What I would add is we’re not running low on those things,” the CBP official told a reporter who asked about donations of feminine hygiene products and food. “We’re using operational funding to provide those things… those things are available now and they have been continuously. So, we are looking at the possibility of using some of those donations going forward. But those items, it’s important to note, are available now we’ve used our own funding to buy those things.”

The official denied allegations that children are not being fed adequately at the Clint facility, saying that children are fed three meals a day and given snacks. “I don’t buy that,” the official said, according to the transcript. “So that’s a little disheartening to hear those allegations for us, frankly.”

The official also said children are allowed showers every 48-72 hours, depending on the number in custody.

On Monday, about 300 children were removed from the Clint facility, but on Tuesday CBP moved 100 children back. In a statement to TIME, a CBP spokesperson said this was a part of the transfer process to move the children into Health and Human Services (HHS) custody. The CBP official speaking during Tuesday’s conference call said no additional resources have been provided at the facility since, however, and that an investigation is underway regarding the allegations against the facility.

“CBP continues to utilize all available resources to prioritize and care for children in our custody and facilitate their expeditious transfer to HHS custody,” said the spokesperson in a statement.

CBP also confirmed to TIME that John Sanders, the acting head of CBP resigned on Tuesday effective July 5, amid the ongoing allegations.

The donors

Austin Savage, 38, and five others returned to the facility on Monday afternoon after trying to donate supplies on Sunday with no luck. They stood outside with boxes of diapers, wipes and some plush dolls, “because, you know, if you’re trying to sleep on a concrete floor in a strange place, who knows what might comfort [you],” Savage tells TIME.

They said they rang a door intercom multiple times that connected the group to an agent, where they left a message but received no reply. After about an hour, Savage says the group gave up and turned to a shelter in the nearby town of San Elizario, where they ended up donating the items.

“These facilities are where this inhumanity is happening. [It’s] a conscious choice by our government,” Savage says. “Which means that we’re all culpable.”

The donations were initially purchased online by a Washington, D.C. resident, who didn’t respond to comment. Savage, who lives in El Paso, agreed to pick up the order and organized a group of five others, who also purchased products. Together they delivered the items to the facility.

In the group was Orlando V. Cordova, 32, who describes himself as a fourth-generation Mexican-American. “I’ve loved growing up in America,” he said. “I had a good education and I’ve learned about history. There’s a lot of good things that America has, but there’s also been times in our history where protest was necessary… I didn’t want to be a person who knows these things but takes no action.”

Acuña spent parts of his childhood near the Border Patrol facility in Clint, where his parents still live. On Sunday he drove to visit them and other family members, and began thinking about the children at the facility.

“I’ve been frustrated by the whole situation,” Acuña tells TIME. “It’s been about who’s blaming who, and whether or not [migrant children] should be allowed to have these types of items — hygiene items and basic needs — and nobody is actually doing anything, no actual action. If the government’s not going to do anything, let the community help… Jesus Christ, it’s just soap and toothpaste.”

“When I go to my parent’s house and my brother’s there with my niece and she’s nine months old and I’m just thinking, I just can’t help but think of those kids,” he said. “They have nobody.”

What happens to the children now?

According to a statement to TIME by CBP, preparations are underway to move the children into the custody of the United States Department of Health and Human Services. In HHS, children are often put into the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement. Local shelters are preparing to receive some of the children.

“We move folks around based upon the crisis we have at hand, frequently,” said a CBP official, according to the transcript provided to TIME. “We have to [do this] because of the overcrowding at our facilities based upon the current flow.”

Dr. Lanre Falusi, a pediatrician and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) spokesperson, said children should not be experiencing detention at all. Some AAP pediatricians have also toured Border Patrol facilities that are housing migrants. “Studies have shown that children will show signs of physical and emotional stress when they’re detained,” Falusi tells TIME. She described examples of children who have experienced developmental delays, regressed or developed behavioral issues such as anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation after being detained.

“And this is not just in the short term,” she said. “Even looking long term, when kids are subjected to these conditions, when kids are afraid 24/7, it effects their nervous system, their endocrine system and has repercussions in the future for their emotional and physical health.”

On Tuesday evening, Congress passed a bill to provide $4.5 billion in supplemental funding to CBP to provide better humanitarian assistance to children in custody, which was met by contention by several other Democrats. The $4.5 billion will go towards legal assistance, beds, food, diapers and alternatives to detention (and contains restrictions on how the money can be spent). The Senate is drafting a similar bill with less restrictions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com