The harsh treatment by police that provoked the uprising at Stonewall 50 years ago this June was hardly a departure from the way LGBTQ people had been treated throughout American history.

At the time of the country’s founding, European countries had laws that criminalized — often to the point of capital sentences — gay men and lesbians for engaging in sexual activity with one another. The United States penal codes followed suit. Colonial laws proscribed the death penalty for these acts. Although infrequently enforced, it was an ever-present reality and threat. Richard Cornish was hanged in Virginia colony for sodomy in 1625. In 1629 “five beastly sodomiticall boyes” who confessed to having sex with one another were hanged in New England. In 1777, reform-minded Thomas Jefferson, to rid the Virginia penal code of its monarchial vestiges, recommended that the less harsh penalty of castration replace the death penalty for men convicted of sodomy. Hundreds of year later, well into the 20th century, gay men and lesbians were shunned, arrested and imprisoned for consensual sexual activity in private.

But that long and disturbing history of punishment was often counterbalanced by the voices of liberation — and many of the arguments that have been prioritized by the modern LGBTQ movement can be traced deep into the past.

For example, since its inception, the LGBTQ movement has prioritized the decriminalization of same-sex activity. This state-by-state project took over half a century and culminated with the 2003 SCOTUS decision in Lawrence v. Texas, which made same-sex sexual activity legal in every U.S. state and territory. Some of the arguments used to win that case were used more than a century earlier by Victoria Woodhull, a late-19th century feminist and radical social thinker whose political ideas, legal arguments and commitment to sexual freedom have been an unacknowledged inspiration for the LGBTQ movement.

Some would find her an odd choice to be included in the scope of queer history. Woodhull was not a lesbian. She never spoke or wrote about same-sex desire or behavior. Yet in her writing and speech, Woodhull claimed that she had “a constitutional right” to her private behavior and her love life. Her radical ideas about the natural and legal right of individuals to freely choose their affectional and sexual relationships without government interference or punishment are, in many ways, the cornerstone of the LGBTQ-rights movement.

Woodhull’s boundary-breaking made her famous during her lifetime. She and her sister Tennessee Claflin were the first women to run a Wall Street brokerage film, and the first women to own and publish a national newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly. She also became the first women to run for President of the United States when she, with Frederick Douglass as her running mate, was nominated by the suffrage-fueled Equal Rights Party in 1872.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

It was her commitment to, and promotion of, the Free Love movement, however, that made her notorious. Free Love was a robust, national, often middle-class phenomenon that emerged from utopian socialism, early feminism and the deep American tradition of resistance to government. An early precursor to the sexual liberation ethics of the 1960s, Free Love argued that the government had no right to dictate how people arranged and lived their personal and sexual lives. Free Lovers did not advocate open marriage, polyamory or indiscriminate promiscuity but only that both women and men should be free to make any decisions about love and sex they chose without intrusion from the state.

Woodhull, in her famous 1871 The Truth Shall Set You Free speech to three thousand people at Manhattan’s Steinway Hall — at 71 East 14th Street, a 15-minute walk from where the Stonewall Riots occurred just a century later — stated these beliefs succinctly:

Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere. And I have the further right to demand a free and unrestricted exercise of that right, and it is your duty not only to accord it, but, as a community, to see that I am protected in it. I trust that I am fully understood, for I mean just that, and nothing less!

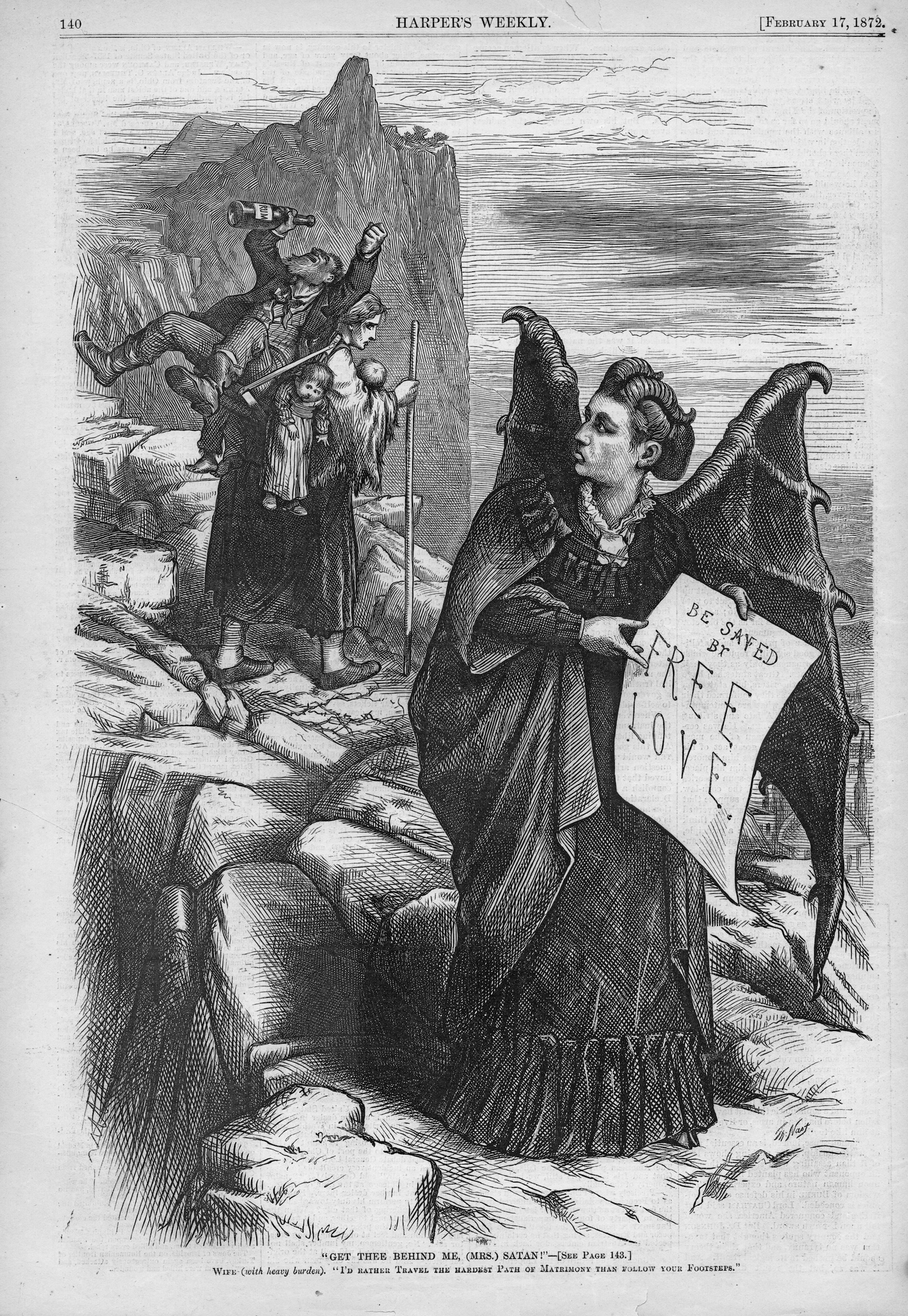

The speech, as we say today, went viral. Woodhull, now the face of the movement, was labeled “Mrs. Satan” by the political cartoonist Thomas Nast. Free Lovers were seen by social conservatives to be a dangerous menace to social norms and public morality: not dissimilar to how LGBTQ people have been viewed in and past, and by some, even today.

With all of the gains made by the LGBTQ movement in the last half-century, from marriage equality to laws against discrimination, it is easy to forget that, from its conception to the present day the LGBTQ movement is, in essence, a sexual liberation movement — a movement to promote the freedom to engage in consensual sexual behavior without social, legal or political interference from the state.

Even after Lawrence v. Texas, gay men and lesbians are harassed, assaulted and even murdered in America for their presumed sexual behavior. Violence against transgender people, simply for being who they are, has increased. The last men executed in a western country for having homosexual sex were James Pratt and John Smith, hanged in London in 1835. But today, execution is still the penalty for same-sex behavior in some non-western countries. The fear and hate that drives this persecution is rooted in fear and hate of the sexual behaviors — and Victoria Woodhull’s belief in the “natural right to love” is still being grappled with today.

Historians’ perspectives on how the past informs the present

Michael Bronski is the author of A Queer History of the United States and A Queer History of the United States for Young People, and a professor of the Practice in Media and Activism in Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Harvard.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com