Over the past 15 years, I have helped a number of presidential candidates prepare for debates, and I am certain the 2020 contenders are feeling the pressure to have a breakout moment in their upcoming first round. But anyone looking to these events for clarity on the direction this race will take is likely to be disappointed. I know we’re all tired of hearing that it’s early, but the reality is we are just six months into an 18-month process leading to the Democratic nomination. Moreover, given the number of candidates onstage each night, it’s unlikely that anyone will speak more than 10 minutes. Unless someone sets himself or herself on fire, it’s hard to see how any of them turns this into a game changer.

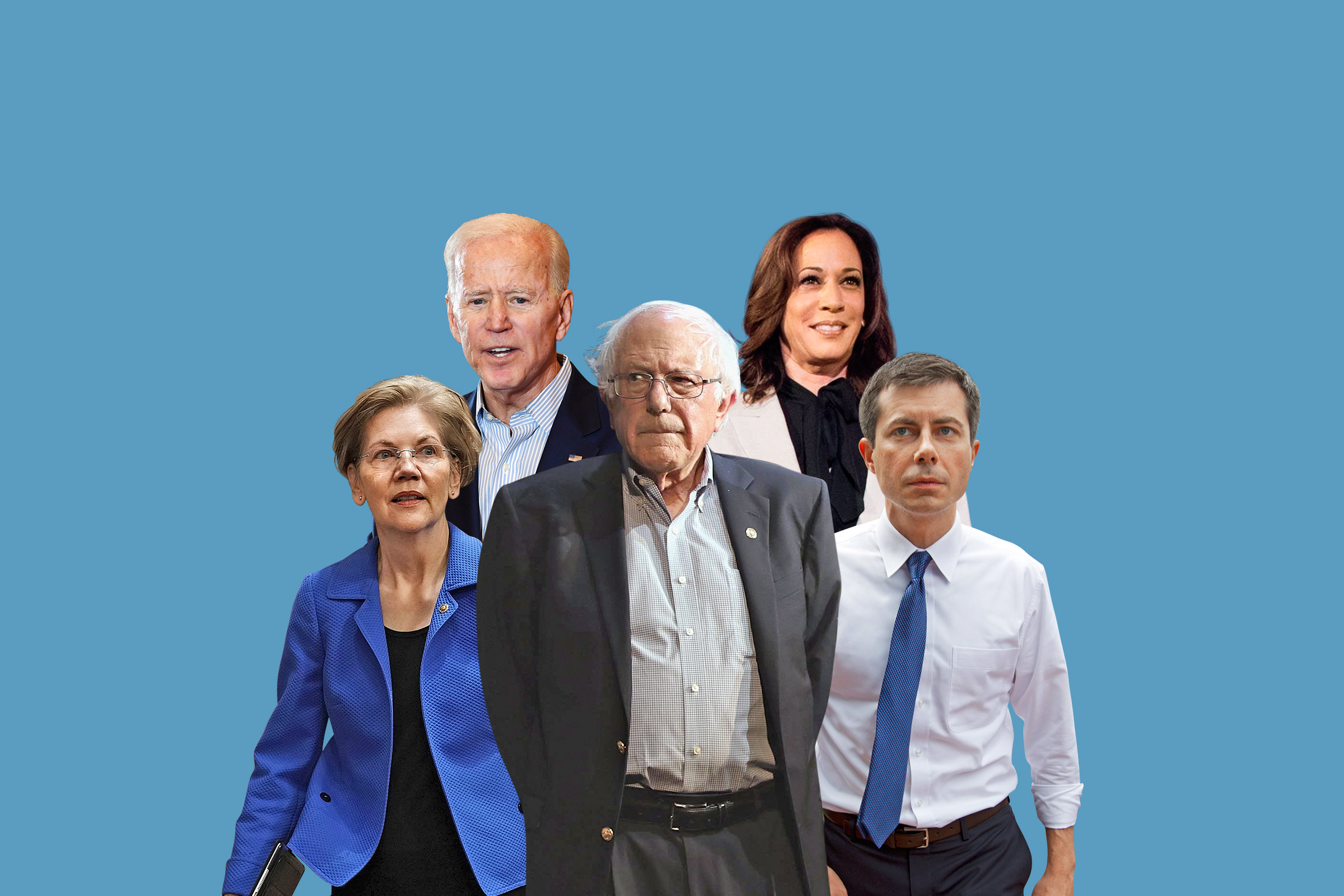

Nevertheless, the start of debate season signals a new phase of the campaign. Candidates like Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders have benefited from the relative anarchy of a large field–it’s been hard for the others to break through the cacophony and relatively easy for the front runners to skirt questions they’d rather avoid. But on the debate stage, the front runners will have to answer the moderators as well as face the specter of attacks from other candidates.

Not that I recommend going after the other candidates in this first outing, particularly Biden. He’s the front runner for a reason–people like him. If attacks on him or his record aren’t delivered deftly, they will elevate him and make the attacker look desperate. Attacking front runners–particularly in early debates–is tricky to pull off, as 2016 Democratic contender Lincoln Chafee learned when he questioned Hillary Clinton’s judgment in the first primary debate in 2015. A blasé Clinton offered a simple “no,” to cheers from the audience, when moderator Anderson Cooper asked if she cared to respond. I’m not sure Chafee had a chance to be a serious contender, but he never recovered from that misfire.

Rather than myopically focusing on the first debate, campaigns should devise a plan for how to use each of the first three, and the time in between, to advance their message going into the fall. It’s not just that the candidates are onstage together for two nights in June. It’s the promise that they will be there again in July, and in September, and so on.

I’m not advising a candidate this cycle, but if I were, I’d suggest a strategy like this: Start by using journalists’ interest in the lead-up to the debate to reset your message and rationale with the press. Second, lay down your best arguments in the debate, and plant some seeds for issues you want to come back to on the trail and in future debates. Third, pick a couple of moments coming out of the debate to capitalize on–great ones by you or openings from an opponent’s gaffe–to drive your message in the next few weeks. Fourth, come back in July and do it again.

In the 2016 Clinton campaign, we tried to do this by crafting debate strategies that set up a discussion we wanted to have on the trail. This worked well in the third primary debate as a means of forcing a conversation about gun control, as we aimed to make that issue a point of differentiation with Sanders and continue to talk about it for the next two months. A less successful example was in the first general-election debate, when Clinton raised Donald Trump’s humiliating treatment of former Miss Universe Alicia Machado to highlight his disrespect for women. It led Trump to go on a multiday spree attacking Machado. The spree was not good for Trump but also drowned out any positive message we tried to drive out of that debate, although of course Trump often defied the traditional playbook.

Candidates in the 2020 field have the opportunity to use the first debate this way. Known for having a plan to solve all problems, Elizabeth Warren should argue that she has the right plan. Her proposal for providing free tuition at all public universities and colleges is controversial, but by using her time to talk it up, she’d be inviting a fight she wants to have. Kirsten Gillibrand has made her support for women a centerpiece of her campaign. She should focus on the new abortion restrictions in Georgia and other states and point to them as a reason to elect a woman. It’s an edgy tactic, but again, it leans into a fight she would welcome and is true to what she believes.

This comprehensive approach may take more planning than coming up with a killer line that will lead the news the next morning. But a strategy that treats the debates as an organizing principle for your campaign is likely to be more successful than gunning for a June breakout moment in Florida when what you need to be building toward is a February breakout in Iowa.

Palmieri is the former director of communications for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com