In a 1954 newspaper article about the murder of a man named Anthony Lankford, two sentences had been underlined: The sailor charged with the crime “had admitted meeting Lankford at a bar on Friday night.” It continued, “He said the two had several drinks and then went to Lankford’s apartment.”

The man who had presumably underlined the sentence was the writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten, in whose papers, held at Yale, I had found a scrapbook containing a series of articles about the crime. And while the words he chose to highlight might seem innocuous on their own, they are in fact a key clue to what this story is really about — and to a troubling truth about life for queer Americans at the time.

Van Vechten was a pivotal figure in American modernism, and an early promoter of African-American writers and artists in the 1920s and 1930s, known for escorting his white bohemian friends into the jazz clubs of Harlem, and in turn bringing African American artists and writers into the downtown salons of Greenwich Village at a time when such racial crossings were rare. He was also a man of sexual crossing. While he was married twice, the second marriage lasting until his death, his homosexuality was a well-known open secret.

Van Vechten was known for his collecting, and the scrapbooks I was looking at were filled with the ephemera of queer life in midcentury New York, including fliers from drag balls, advertisements for queer novels, homoerotic collages and a number of crime stories clipped from the newspapers, including the articles about Lankford’s death.

The 29-year-old insurance executive was beaten, shot in the head and had his throat slit with a broken glass at his “bachelor apartment” in Bucks County, Penn. The assailant, a former sailor, claimed in court that his violent attack was triggered by Lankford’s “indecent advance” — a common phrase in the press at the time to indicate violent, sexual threats. “I don’t remember inserting the glass into Lankford’s neck, but I do remember pushing it,” the press reported on the sailor’s confession. And then there was that underlined sentence, the clue for the reader about the implied queer nature of the crime. Months later, the judge sentenced Lankford’s killer to a prison term of 7 to 15 years for second-degree murder.

The mixture of crime stories within this scrapbook of queer life intrigued me. What, I wondered, can true crime help us understand about queer history?

Today, 50 years after the Stonewall uprising that marks the birth of the modern gay-rights movement, we may understand that violence against LGBTQ citizens has been central to the evolution of that movement. But the history of such crimes tends to be lost. We may know abstractly that queer people suffered injuries on the streets and in the courtroom, lacking any legal protections. Yet what were the nature of these crimes, and how did the press and criminology play a role in the criminalizing queer citizens?

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

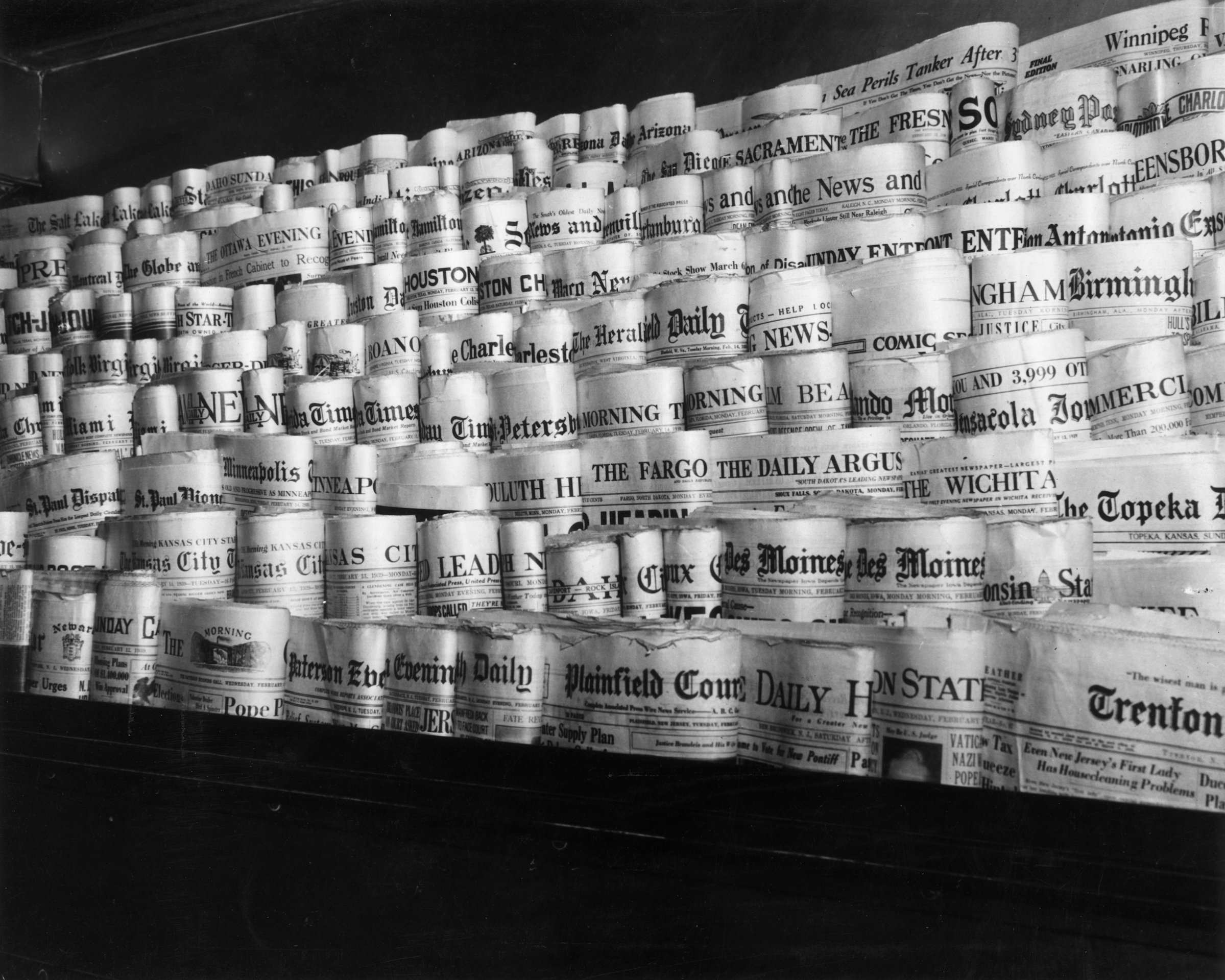

When I first started this research, few newspapers had digitalized their archives, making it nearly impossible to search for such crimes. Newspapers did not catalog “gay murders” in the decades before Stonewall. Even when the indexes began using the word “homosexual” in the late 1930s, it wouldn’t get me too far beyond sensationalized accounts or opinion pieces about “sex deviants.” But as more newspaper collections were digitalized, a new research strategy opened up. I could now focus on particular search terms such as “man found slain in hotel,” or “man found beaten in park” or “sailor found murdered.” These searches eventually produced pages and pages of articles that I would sift through searching for the clues to queer crime stories. From these leads, I searched the names of the victims or killers, which usually generated additional articles detailing the crime scene, the search for the assailants, arrests reports and, sometimes, reports on the court trials and sentence hearings.

The murder of Walton Ford, a southern transplant to New York City in the 1930s was a case in point. Walton’s body was found badly beaten and tied up in his East Side apartment, and the crime made headlines across the country. The press reported on the “blood splattered room” of Walton’s apartment, offering readers both salacious and shocking details. When two men were arrested for the murder, they claimed they had met Walton at a local bar, and to have returned to his apartment on Walton’s invitation. After a few drinks, according to the press, the men “strangled him, lashed him to his bed, and escaped with $40 from the bureau drawer.” Although indicted on first-degree murder charges, the two assailants pleaded guilty to the lesser charge of second-degree murder. The press noted that Ford’s relatives wanted to “avoid the possible notoriety of the murder trial.”

While such fears underscored the shame induced in the victim’s relatives if the details of the crime were made public, it also meant that defendants were given lesser sentences for such brutal crimes. But this reticence was understandable in an era when queer men were so routinely portrayed as criminals. As sodomy was a felony in every state, the victims were often viewed as complicit in their own violent deaths at the hands of men they invited back home.

While in the decades before Stonewall the press was not shy about amplifying fear of sex deviants — coded phrasing that could apply to people ranging from pedophiles and rapists to otherwise law-abiding homosexuals — it was less eager to detail accounts of queer men brutally beaten or murdered. “The presence of homosexuality as a factor” in crime stories, wrote one commentator in the early 1940s, “has long been discreetly presented in our newspapers.” Reading between the lines was required to see the underlying realities of the crime. Details like the ones that brought the two killers into Walton’s apartment — a meeting in a bar and returning to the victim’s apartment or hotel room, where an argument turns violent — were common elements in queer true-crime accounts, as the press hinted at the layers that simmered beneath the crime.

As I began to dig deeper into the archives, more articles like those about Walton’s murder surfaced, and I got better at reading the clues, finding the queer subtext between the lines. In the post-World War II years, the press became more explicit about the homosexual context of crimes, pointing readers to the fears and threats queer men presented to Cold War America — even in crimes where they were the victims of brutal and gruesome killings.

In this sense, the history of queer true-crime stories is a history of the criminalization of queer citizens. Resistance to that situation was at the heart of the early gay rights movements in the 1950s and 1960s, and on into what happened at the Stonewall Inn in June of 1969. When patrons dared to push back against police raids, it was a reaction not just to the political consciousness of the late 1960s, but also to the overt forces that had criminalized queer people in the press and the courtroom for decades.

James Polchin is the author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall, available now.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com