He wanted to go as soon as he heard.

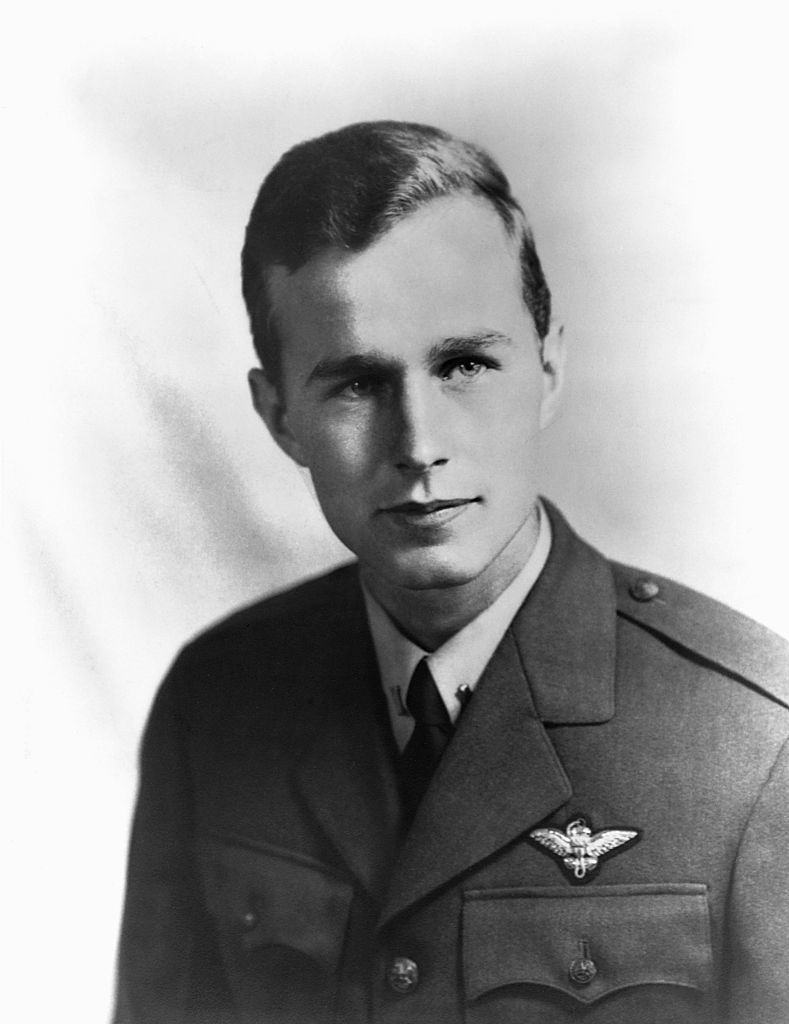

On the afternoon of Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, George Herbert Walker Bush—known as “Poppy” to family and friends—was walking on the campus of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, when word came of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was 17-and-a-half years old. He longed to defend his country—right then, right away, no waiting around. Told he would have to turn 18 before he could enlist in the U.S. armed forces, a determined Bush explored the option of going to Canada to join the Royal Air Force. He was that ready to risk everything for a cause larger than himself.

And so there it all was, even in the beginning: a boundless energy and a hunger to serve; a thirst for adventure and a love of country. Six months later, on Friday, June 12, 1942, he marked his 18th birthday, he graduated from Andover, and he drove to Boston to be sworn in as a naval enlistee. From that day until his death more than 75 years later, on Nov. 30, 2018, George H.W. Bush served his country in sundry capacities—including a notable term as president of the United States in an era of what he called “a fascinating time of change in the world itself.”

George H.W. Bush was not a president largely in the tradition of the soldier-statesman Dwight D. Eisenhower, who said that his goal was to take America “down the middle of the road between the unfettered power of concentrated wealth . . . and the unbridled power of statism or partisan interests.”

Moderate in temperament, Eisenhower and Bush were both more traditionally conservative than many of their contemporaries understood, in the sense that they sought above all to conserve what was good about the world as they found it. For them conservatism entailed prudence and pragmatism; they eschewed the sudden and the visionary.

History tends to prefer its heroes on horseback, at least figuratively: presidents who dream big and act boldly, bending the present and the future to their wills. There is, however, another kind of hero—quieter, yes, and less glamorous—whose virtues repay our attention. Hero itself comes from the Greek word meaning to defend and to protect, and there is greatness in political lives dedicated more to steadiness than to boldness, more to reform than to revolution, more to the management of complexity than to the making of mass movements. So it was for Eisenhower, and so it was with Bush. Eisenhower’s favorite motto, inscribed on a paperweight he kept on his desk in the Oval Office, was “Gently in manner—strongly in deed.” Bush’s life code, as he once put it in a letter to his mother, was “Tell the truth. Don’t blame people. Be strong. Do your Best. Try hard. Forgive. Stay the course. All that kind of thing.” Simple propositions—deceptively simple, for such sentiments are more easily expressed than embodied in the arena of public life.

Bush believed in the essential goodness of the American people and in the nobility of the American experiment. His understanding of the nation and of the world seems antiquated now; it seemed so in real time, too, at least in the last year or so of his presidency. But there was nothing affected about Bush’s vision of politics as a means to public service, of public service as the highest of callings. This vision—of himself engaged in what Oliver Wendell Holmes called the passion and action of the times—was as real and natural to him as the air he breathed. It was his whole world, and had been since his earliest days when he would watch his father come home from a day on Wall Street only to head back out to run the Greenwich Town Meeting. It was as simple—and as complicated—as that.

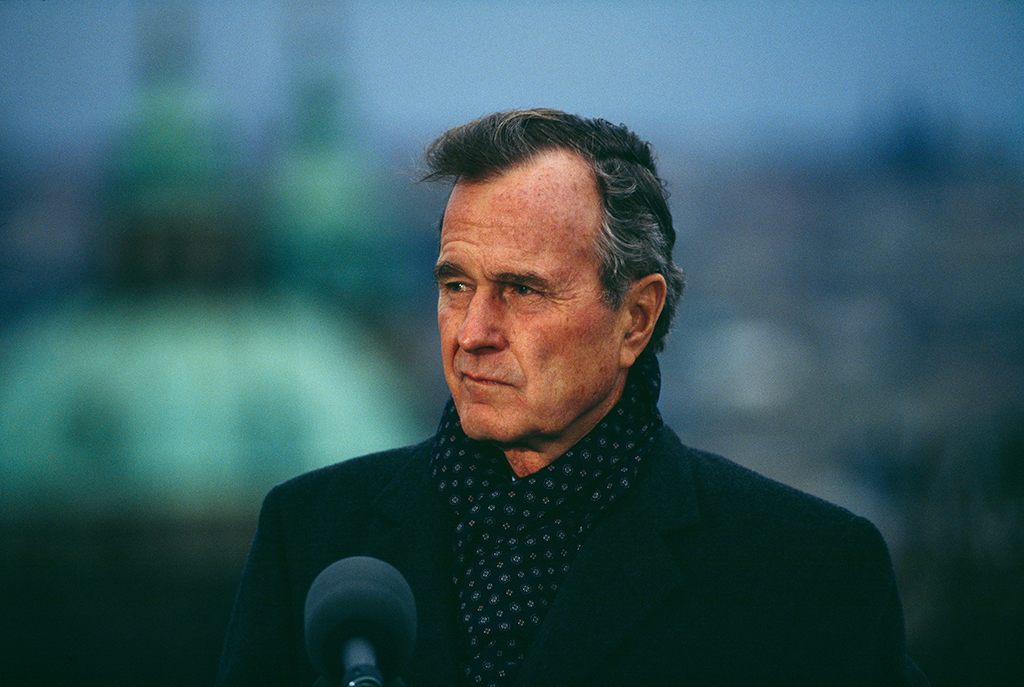

A formidable physical presence—six-foot-two, handsome, dominant in person—he spoke with his strong, big hands, making fists to underscore a point, waving dismissively to deflect unwelcome subjects or to suggest that someone was, as he would put it, “way out there,” beyond the mainstream, beyond reason, beyond Bush. Television conveyed his lankiness, but not his athleticism, his grace, and his sturdiness. Bush was a master of what Franklin Roosevelt once called “the science of human relationships,” and his capacity to charm—with a handwritten note, a phone call, a quick email, a wink, a thumbs-up—was crucial to his success in public life and was an essential element of his soul.

A child of one generation’s ruling class, the head of another’s, and the father of yet a third, Bush led an epic life that ranged from the Gilded Age of railroad barons to the birth of Big Oil, from Skull and Bones to the tennis courts of the Houston Country Club, from Greenwich and Midland to Washington and New York to Baghdad and Beijing. He embodied two competing forces in American life after World War II: the global responsibilities of a vital atomic power in foreign affairs and the rise of the cultural right wing in domestic politics—forces that fundamentally shaped the second half of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st.

“How great is this country,” Jeb Bush once said, “that it could elect a man as fine as our dad to be its president?” The remark came in private, without agenda; it so struck Laura Bush that she included the moment in the White House memoir she wrote after she and George W. left Washington in 2009. As the years passed, Jeb’s sentiment became relatively common. The 41st president represented the twilight of a tradition of public service in America—a tradition embodied by FDR, by Eisenhower, and by George H.W. Bush. “My father was the last president of a great generation,” George W. Bush said in accepting the Republican presidential nomination in 2000, eight years after his father’s defeat. “A generation of Americans who stormed beaches, liberated concentration camps and delivered us from evil. Some never came home. Those who did put their medals in drawers, went to work, and built on a heroic scale … highways and universities, suburbs and factories, great cities and grand alliances—the strong foundations of an American Century.”

It was Bush who quietly but unmistakably laid the foundations for the 21st. He brought the Cold War to a peaceful conclusion, successfully managing the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany, and the end of the Soviet Union without provoking violence from Communist bitter-enders. In the first Gulf War, Bush established that, on his watch, America would not retreat from the world but would intervene, decisively, when the global balance of power was in jeopardy.

On the home front, his 1990 budget agreement controlled spending and created the conditions for the elimination of the federal budget deficit under Bill Clinton. He negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement; signed the Americans with Disabilities Act; and passed historic clean-air legislation.

His life was spent in the service of his nation, and his spirit of conciliation, common sense, and love of country will stand him in strong stead through the ebbs and flows of posterity’s judgment. On that score—that George H.W. Bush was a uniquely good man in a political universe where good men were hard to come by—there was bipartisan consensus a quarter century after his White House years.

He was a decent man who did what it took to win, a gentlemanly sportsman who was a relentless competitor, a statesman who believed that campaigning was one thing, governing quite another. Bush was a steward, not a seer, and made no apologies for his preference for action—steady, prudent, and thoughtful—over ideology. Born in the aftermath of the Great War, he fought and nearly died in World War II and spent much of his life living with the reality of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Unflinching creeds and consuming worldviews could lead to trouble, for devotees of doctrine tended to fall in love with their own sense of certitude and of righteousness, ignoring inconvenient facts. And he believed that if a president were self-absorbed, too focused on his own fortunes, then he would not be the best protector of the fates of others. The best presidents, he believed, put the national interest ahead of self-interest—no matter what the price.

The farther the country moved from his presidency the larger Bush loomed, and the qualities so many voters found to be vices in 1992—his public reticence; his old-fashioned dignity; his tendency to find a middle course between extremes—came to be seen as virtues. He lived long enough to see the shift, and he appreciated that people were taking a more benign view of his record. Amid a conference at his presidential library in his 90th year, a visitor asked him what he made of all the encomiums and positive revision of his legacy. “Hard to believe,” Bush remarked. “It’s ‘kinder and gentler’ all over the place.”

Now he is mourned not because he was perfect, but because he sought to serve the nation in whose defense he first enlisted so long ago at Andover, when he began his long walk into history.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com