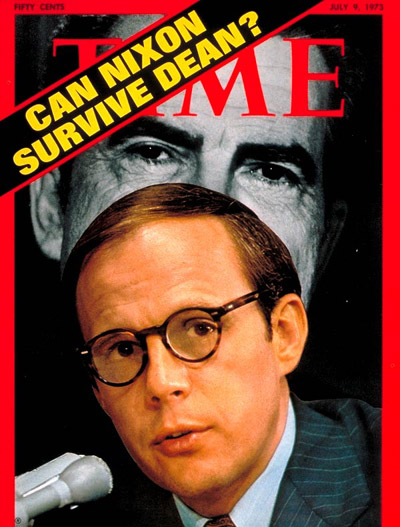

Pundits have been drawing comparisons between President Donald Trump and President Richard Nixon for basically as long as Trump has been in office, and especially since Special Counsel Robert Mueller began his investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election, but those comparisons don’t usually come from Trump himself.

An exception came on Sunday when President Trump tweeted, in light of news that White House Counsel Don McGahn had met with Mueller’s team, that McGahn wasn’t a “John Dean type ‘RAT'” because he wasn’t testifying behind the back of the White House.

Dean, as Nixon’s White House Counsel, played a key role — by deciding to cooperate with prosecutors — in events leading up to the President’s resignation in 1974. Tapes validated his Senate Watergate Committee testimony about the President’s role in the attempt to cover up the break-in at the Watergate office of the Democratic National Committee; Dean pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice for his role in the cover-up and spent four months in confinement at Fort Holabird.

“I certainly didn’t want to commit any crimes,” he told TIME in a Tuesday afternoon phone call, “and I wish that I had had somebody I could draw on or somebody’s experience I could have drawn on.”

As it turns out, there was somebody who could draw on his experience — namely, Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal lawyer, who on Tuesday pleaded guilty to tax evasion, campaign finance violations and making false financial statements, and made statements under oath about his actions during the Trump campaign. Cohen’s plea came on the same day that a jury found former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort guilty of eight counts of bank and tax fraud related to his work as a political consultant abroad. Dean spoke to TIME about his reaction to that news and what he thinks of his own return to the headlines. Below is the transcript, edited for clarity, of that conversation.

When Michael Cohen appeared in court to plead guilty today, he stated that he arranged payments made to two women who alleged they’d had affairs with then-candidate Donald Trump “at the direction of the candidate” in order to influence the election. What’s your reaction to that?

He has pretty much identified the President as a criminal. He said he did it at his behest. If [Trump] weren’t President, he probably would be named as a co-conspirator and indicted.

What does that mean for the comparisons to Watergate?

It’s conspiracy. Watergate was a conspiracy. This is a campaign conspiracy.

In other news from today, what’s your reaction to the Manafort trial verdict?

It’s not surprising. It’s clear that jury went carefully through the case. I wouldn’t be surprised if they were somewhat affected by the speed with which the judge forced the prosecution to put [the trial] on, [which] made some of it confusing to them, but they seemed to get the big issues. They got the bank fraud, understood that. It’s an opening shot by the Special Counsel. It really sets up the situation that Manafort was in.

What did you think of Trump calling you a rat for your role in exposing the Watergate cover-up?

That just didn’t surprise me at all. Every day, he throws invective at somebody. I was trying to be the honest guy and stop all this nonsense of spinning and lying and twisting history. I was more distressed or annoyed by him calling the true public servants who have taken salary cuts to go to work for Bob Mueller “thugs.” That’s just so uncalled for. These are men who are committed to the rule of law, who are doing the honorable thing. It’s just disappointing coming out of the President of the United States. He’s just denigrating the office every day he’s there.

In recent weeks, and especially after this weekend’s tweet, you’ve found yourself back in the headlines for something that happened decades ago. How does it feel to have basically gone viral?

It’s not surprising. It’s a culmination of what’s been going on. I didn’t know when Michael Cohen was going to plead or work a deal out, but I knew it was imminent because I was talking to his lawyer Lanny Davis, whom I know personally, and he was picking my brain as to what had happened and how it had all happened back during Watergate. He knows that subject pretty well so he was just refreshing his recollection. I wasn’t giving legal advice, just historical information.

Since you and McGahn and Cohen were all in the position of being the President’s lawyer in some way, though in very different situations, one of the questions that has come up is how attorney-client privilege might apply. In McGahn’s situation in particular, since that was how the President drew you in, how do you think that legal concept applies?

McGahn is certainly drawing the right lessons from what I went through. One of the interesting things that was resolved because of Watergate is the whole issue of when a lawyer represents an institution or organization, who the client is. And it’s not the constituents of the organization or entity or whatever you describe it as. It is, rather, the organization itself. So in this instance, they made it very clear that he represents the office of the president and not the man who occupies the office, and there’s a huge difference. Attorney-client privilege certainly runs to his private counsel, but in most instances, does not run to his government counsel. While Trump can obviously hire and fire any lawyer he wants, it’s not likely a public-employee lawyer is going to bear down on him like a private counsel might because I don’t think Trump is the kind of client that most people would recognize who opens up and really tells them what’s going on. I suspect John Dowd [Trump’s former personal attorney] really has not a clue exactly what Trump did and didn’t do.

What happened is Richard Nixon, who is extremely competent, really bungled Watergate and never hired a lawyer who knew how to advise him. [Nixon] didn’t draw on eminent local Washington defense lawyers and Trump has done the same. It’s amazing. Nixon finally hired a good lawyer after he left office. He hired Jack Miller, who had been the head of the criminal division of the Justice Department. But it was too late.

What do you think will happen next?

It’s not clear, unlike Watergate, how the public is going to become educated about all this. There is really no equivalent to the Senate Watergate Committee. The Republicans just won’t set it up. They don’t want to inform the public about this. So as long as they control the House and Senate they’re not going to. Let’s say the House goes Democratic after the election, I suspect we will learn through a combination of oversight committees, if not [by] reinvigorating the intelligence committee of the House under Adam Schiff. It’s really important that the public understands this. That really happens best when you get live witnesses in front of the House and Senate explaining these things.

Mueller’s doing a counterintelligence investigation which properly shouldn’t be made public. It involves a lot of sources and methods that could put a lot of people’s lives and their families in jeopardy by revealing what we know about what the government has learned of Russia’s activities. But it’s vital, and the fact that Trump is doing everything to inhibit that is again unspeakable.

Is there anything you learned during that time that would useful for people to keep in mind as this news develops?

It’s early. Watergate went on for years, and it takes time for the public to one, learn, two, even get interested in learning, and three, react. That’s one of the things that Watergate certainly teaches us.

What’s very useful and what got me through the whole matter was my belief that the truth ultimately prevails.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com