As accusations of treachery continue to swirl around Washington and the White House, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to ignore the specter of a stocky, limping, figure dressed in the tricorn hat and long-tailed coat of a Revolutionary War officer.

Treason has become a talking point on both sides of the aisle. The chaotic fallout from President Trump’s recent Helsinki summit with his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, prompted former CIA director John Brennan to describe Trump’s behavior as “nothing short of treasonous” — and on Monday, Trump’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani mentioned by name the man who, in American history, is synonymous with that idea. “George Washington would have said that about Benedict Arnold at a certain point in time,” Giuliani said during a CNN interview, by way of explaining his earlier praise of Trump’s former attorney Michael Cohen. “George Washington didn’t know that Benedict Arnold was a traitor.”

Now, however, everyone does. Nearly 250 years after he defected to the British, Major-General Benedict Arnold remains among the most vilified figures in American history. Ever since Sept. 25, 1780, when his plot to betray the Hudson Valley fortress of West Point was exposed on the brink of being activated, Arnold has been branded a Judas, ready to barter his honor and country for enemy gold.

What would he think of his name once again making news? We can only guess. But Giuliani’s point does in fact speak to an important element of the real story of Benedict Arnold. And if the testimony of this most notorious American turncoat is any indication, treason — and the motivations behind it — can be far less clear than the public may wish to believe, and history to remember.

Not that the definition of treason is complicated. To the frustration of the President’s critics, Article III, section 3 of the U.S. Constitution narrowly defines treason against the United States as consisting “only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid or comfort.” Americans shared this understanding of treason, rooted in English common law, even before the Constitution was written.

Yet if Arnold had been executed for that crime — in reality, he escaped to the British in New York — some of those who witnessed him swing would surely have felt mixed emotions. Before turning his coat from Continental blue to British scarlet, he’d served the Patriots with conspicuous bravery, helping to ensure that the Declaration of Independence amounted to more than bold words. Without his contribution as a dynamic and resourceful soldier, it’s debatable whether today’s USA would even exist.

Two episodes stand out. In 1776, when a British army was poised to advance south from Canada, Arnold assembled a fleet on Lake Champlain that forced the enemy to halt and construct warships of their own. That October, Arnold’s flotilla was destroyed, but his willingness to fight against heavy odds bought the Americans crucial time — and earned George Washington a timely reprieve. If Britain’s northern force had rolled south as planned, he would have been trapped. Without Arnold’s energy and determination, there would have been no ripostes against Trenton and Princeton, victories that revived the Patriot cause when it was at low ebb.

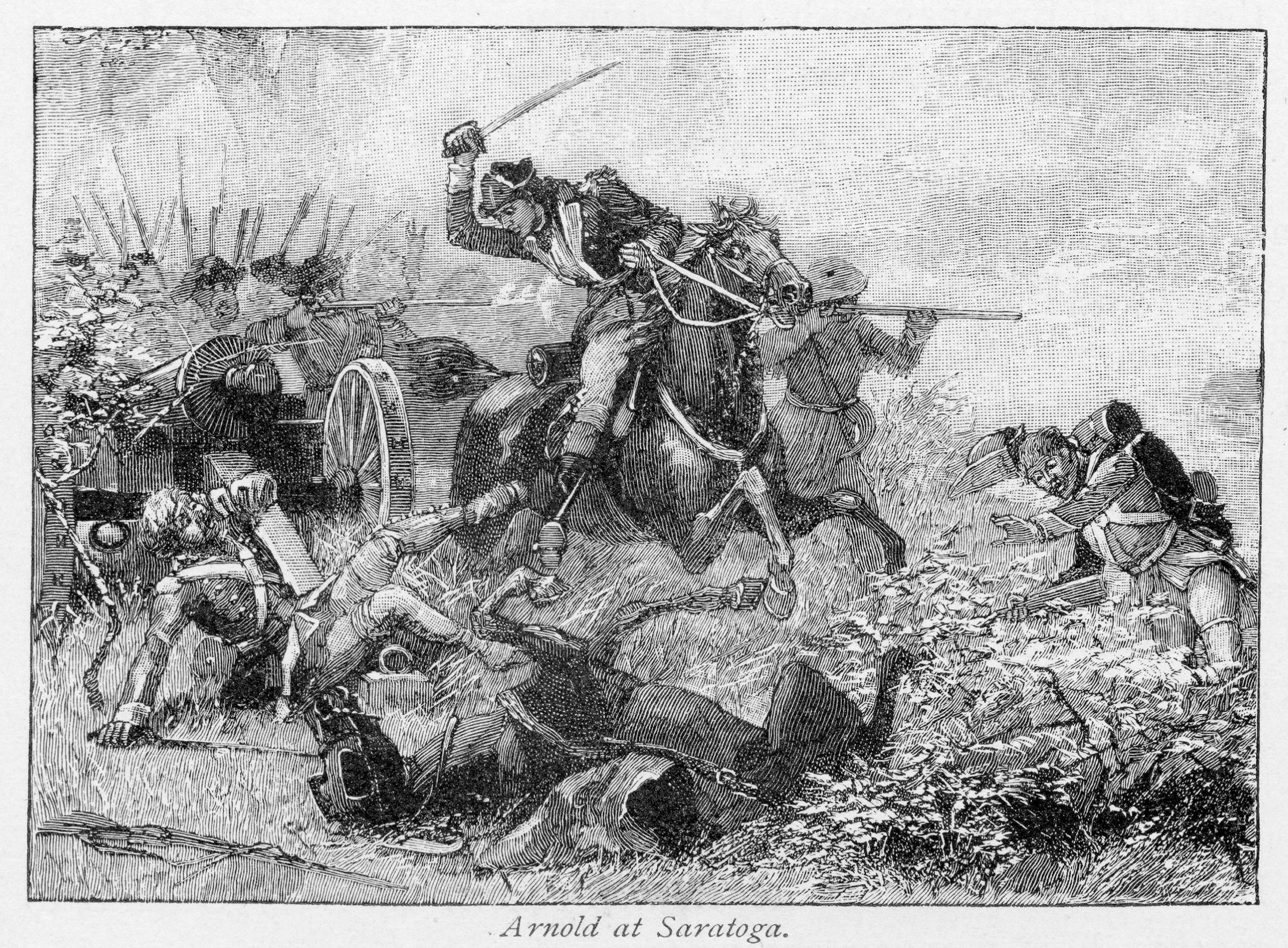

In the summer of 1777, after the British resumed their stalled advance from Canada under General John Burgoyne, Arnold’s role was even more significant for the future of the fledgling republic. By helping to rebuff a British advance along the Mohawk Valley, he clipped one wing of the invading army. When Burgoyne’s depleted forces pushed on for Albany, and encountered the army of General Horatio Gates near Saratoga, Arnold’s aggressive tactics transformed a stand-off into a decisive Patriot victory. That outcome convinced the French to enter the war against Britain, vastly improving the prospects for American independence.

Badly wounded, Arnold was appointed military governor of Philadelphia. But — ironically, considering his own role in bringing the French over to the Patriot side — he soon became convinced that British peace commissioners offered his countrymen a better option than alliance with their traditional enemy. In May 1779, Arnold opened negotiations with the redcoats in New York.

In fact, this was Arnold’s second brush with treason. Like George Washington and other supporters of American independence, when he first took up arms against his legitimate sovereign King George III, he became a rebel, guilty of high treason under English law dating back to 1351. By the Royal Proclamation of Rebellion, issued in London on Aug. 23, 1775, all Crown officers were obliged to use “their utmost endeavours to suppress such rebellion and to bring the traitors to justice.” The official punishment for treason was execution by hanging, drawing and quartering.

But though Patriot prisoners-of-war died by the thousands from disease and neglect, they were never hanged as rebels. Britain was reluctance to unleash the full force of its Treason Act on the American insurgents — though several rebel states (notably Pennsylvania, New York and New Jersey) had no such qualms about employing their own harsh laws against Loyalists who clung to their allegiance to the Crown.

When his conspiracy was uncovered, Arnold was immediately accused of selling his soul for British cash. Since then, historians have acknowledged the role of his prickly, proud personality, and his mounting resentment against politicians who failed to appreciate and reward his services. But a careful reading of all the evidence suggests that Arnold committed treason for what he believed to be honorable reasons, and in the best interests of his distressed fellow Americans. As the British general Sir Henry Clinton reminded him soon after his first approach, “you proposed your assistance for the delivery of your country.” Over the years, Arnold consistently maintained that he’d defected to save America from an ineffective Congress, a cause that had lost its way, and a bloody and protracted civil war. As late as 1792, while exiled in London, he complained about the “illiberal” comments that he’d endured because of the prevailing misconception that his conduct in America had been influenced by “mercenary,” rather than “just,” motives.

But in seeking to justify himself, Arnold was inevitably fighting a losing battle against lingering accusations of cynical betrayal. In 1784, when he applied in vain for a military posting with the East India Company, one of its governors, George Johnstone, underlined the harsh rule that history is written by the winners: “Under an unsuccessful insurrection all actors are rebels; crowned with success they become immortal patriots.” While Johnstone had no doubt of the “purity” of Arnold’s conduct, “the great vulgar herd” thought differently.

As a rebel who’d led his countrymen in a successful war for independence, George Washington was hailed as a national hero, not condemned as a traitor to his lawful king. But Benedict Arnold ultimately picked the wrong side in the Revolutionary War. Irrespective of its motives, his plot had failed. In the eyes of posterity, he would be forever defined — and tainted — by treason.

Stephen Brumwell is the author of Turncoat: Benedict Arnold and the Crisis of American Liberty (Yale University Press, 2018).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com