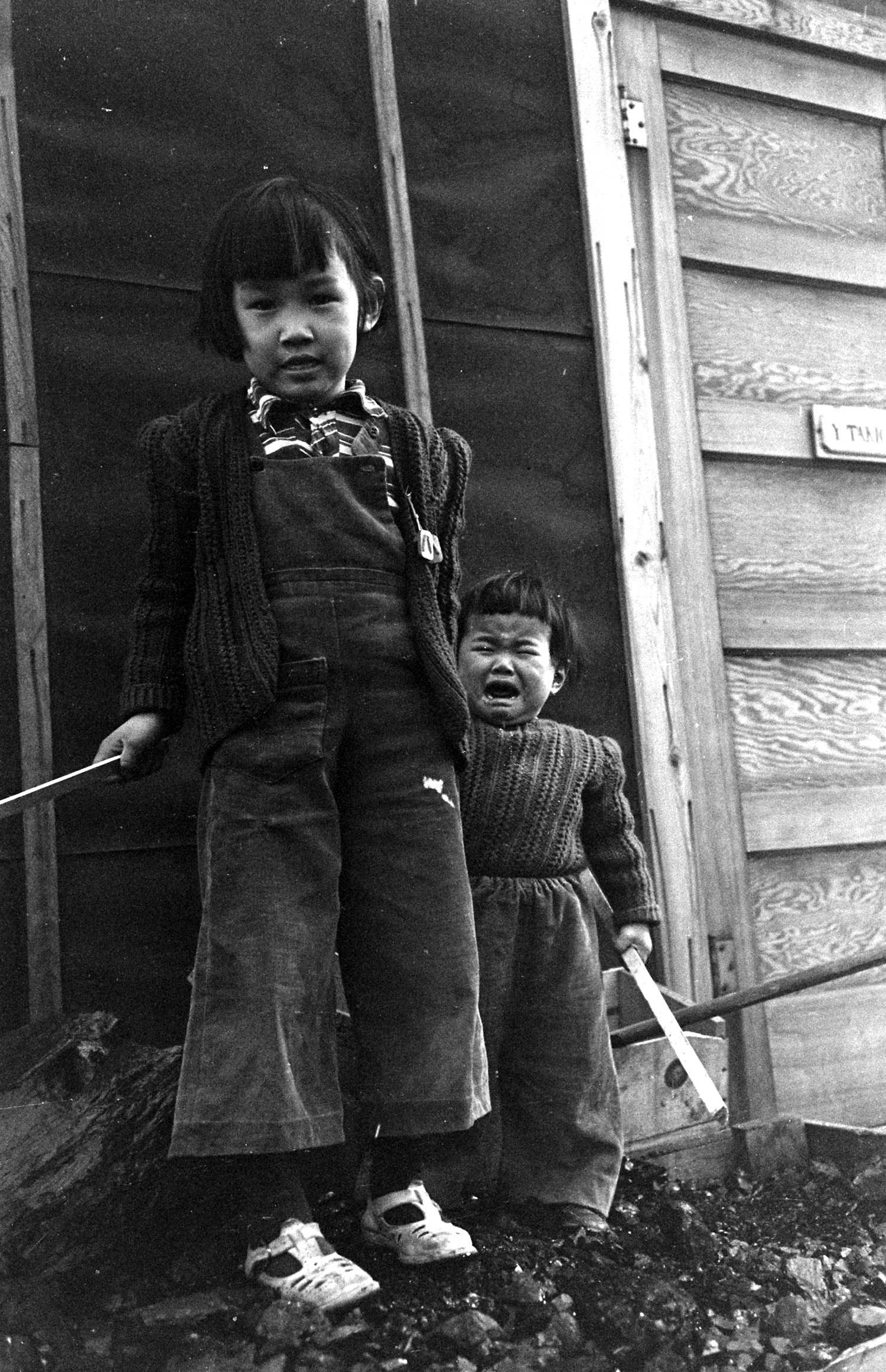

When former First Lady Laura Bush denounced the border policy that has led to the separation of about 2,000 children from their families, in a Washington Post op-ed on Sunday, she drew a parallel between today’s news and a hard-learned lesson from the American past. The images of children being detained in a converted Walmart and a tent city on the Texas border, she wrote, “are eerily reminiscent of the Japanese American internment camps of World War II, now considered to have been one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history.”

Her use of the phrase “now considered” is worth noting. In that case, it took decades for the White House and lawmakers to admit that the U.S. government had been wrong.

It’s been just about 30 years since President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. That law paid out reparations of about $20,000 to every survivor of those internment camps “to right a grave wrong,” as he put it, which the law blamed on “racial prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” But, as noted by Mae Ngai, professor of Asian American Studies and professor of History at Columbia University, the apology and reparations came more than a generation after President Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 led to the rounding up of 120,000 Japanese-Americans, most of whom were U.S. citizens.

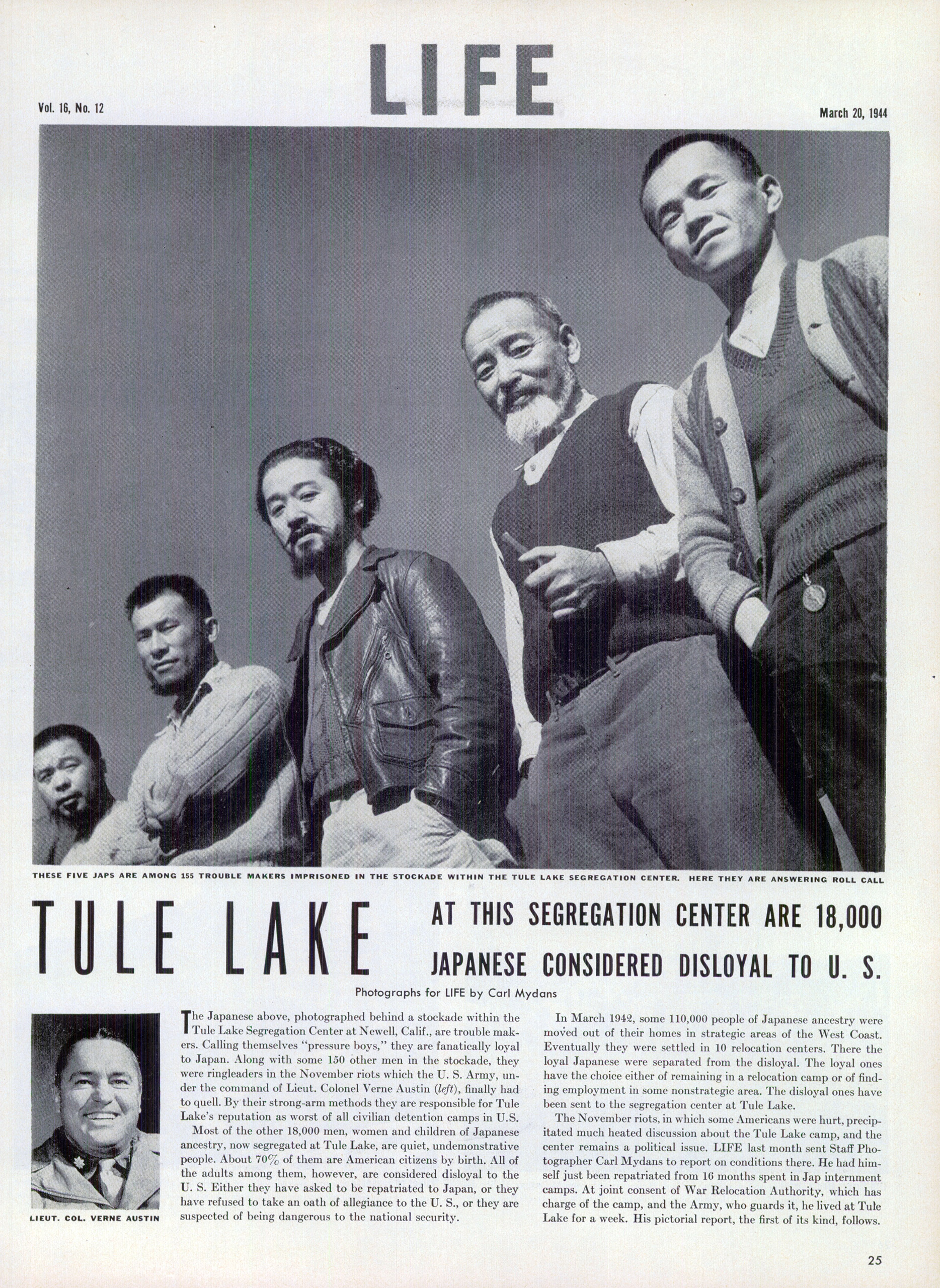

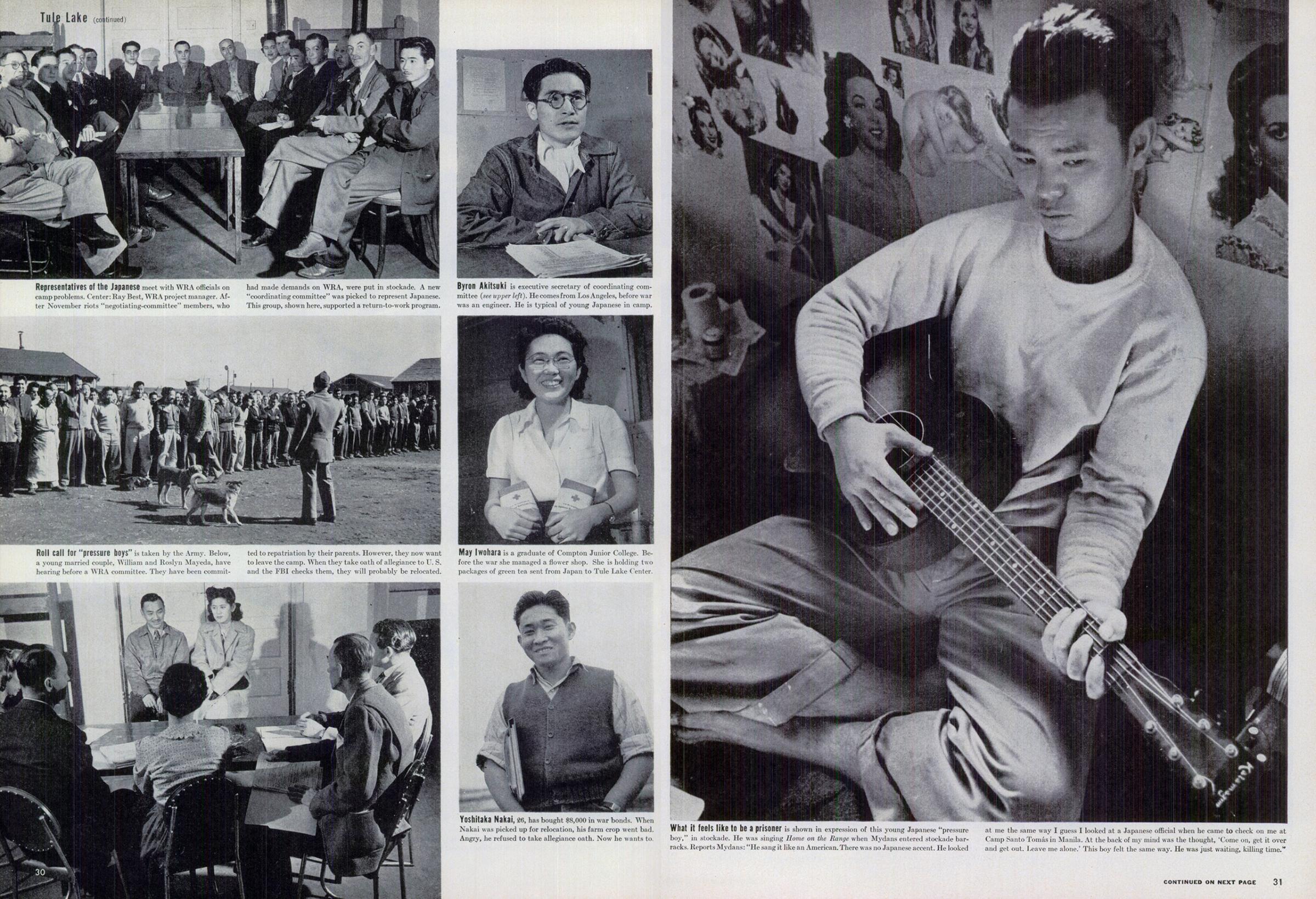

“At the time of the internment, almost nobody opposed it,” says Ngai. “There was widespread support for the internment because of racism and because of government’s claim that Japanese-Americans were a national security threat.”

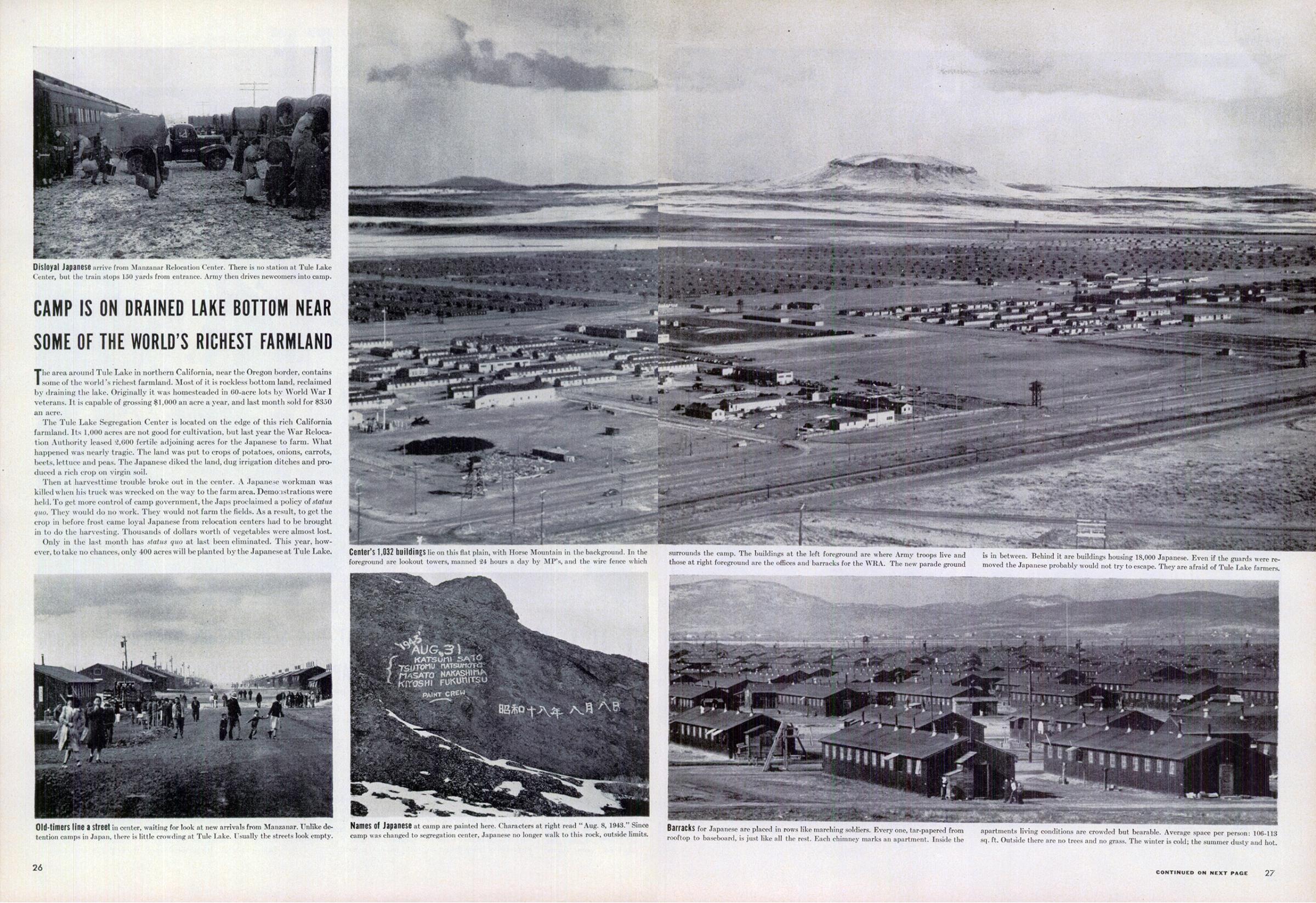

In early 1942, when Roosevelt signed that now-infamous order, the attack on Pearl Harbor of Dec. 7, 1941, was at the top of Americans’ minds. Many worried that, though actual sabotage was confined to rumor, the tens of thousands of American citizens whose families had come from Japan would turn on them. Roosevelt’s order allowed the military to exclude people from certain areas in the name of national security, and that translated to removing the Japanese-American population from much of the West Coast and putting them in camps for years.

Some protested at the start. Sen. Robert Taft was notably, according to historian Eric Foner’s overview of the debate, the only person to speak out in Congress against the order. The Quaker community opposed the move too, and TIME carried a reader letter that asked rhetorically whether there were any “greater atrocity in the annals of American history.” But the decision generally went down well in Washington. Groups like the NAACP and the American Jewish Committee that might be assumed to have opposed the internment did not speak up, and TIME described the mood on the West Coast as a “sigh of relief” that Roosevelt was protecting the people. Sen. Taft eventually stopped his protest. And in 1944, in the case of Fred Korematsu, an Oakland-born steel welder who tried and failed to resist the order to relocate, the Supreme Court upheld the idea behind the internment camps.

It was after the war ended, amid a shift in post-war relations with Japan, Ngai says, that public opinion began to change — slowly.

“As early as the 1950s, once the Communist revolution happened in China, and the Korean War, the U.S. considered Japan its number-one ally,” says Ngai.

By the early 1960s, TIME referred to the internment camps as “an ugly footnote” to the story of the war. Even so, the public apology was still decades away; acknowledging that the camps were “ugly” was not the same as saying they were a bad decision. When the government settled claims for property lost during that period, it avoided passing judgment on FDR’s choice.

“Even though [Japan] was a geopolitical ally, you had, in the ’70s and ’80s, a protectionist movement similar to what you see today — blaming Japanese imports for loss of American jobs, people taking sledgehammers to Toyotas in parking lots and beating up Asian-Americans, like Vincent Chin, the Chinese-American bludgeoned by two auto workers in Detroit,” Ngai says. “The U.S. has always had a complicated relationship with Japan.”

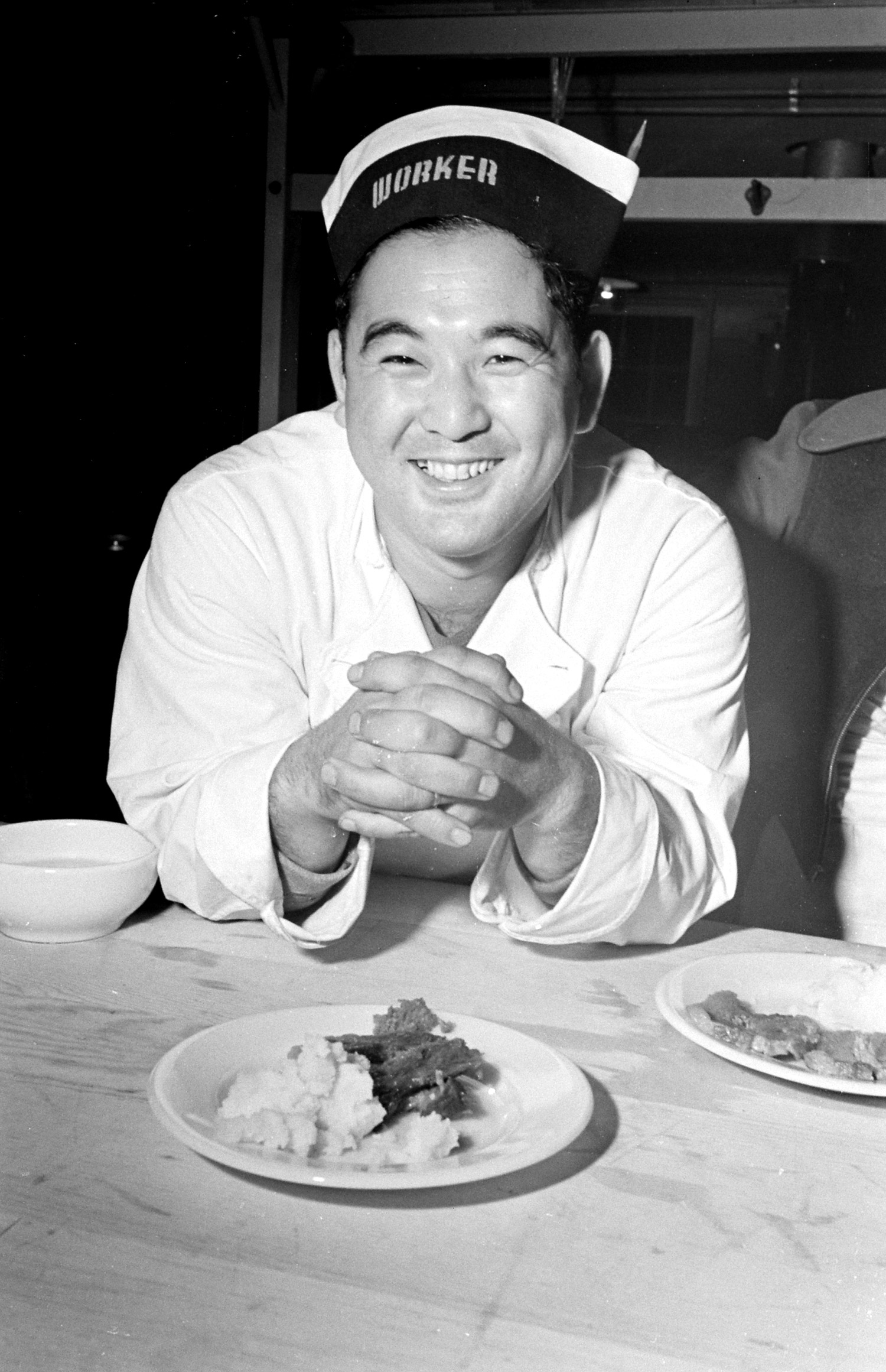

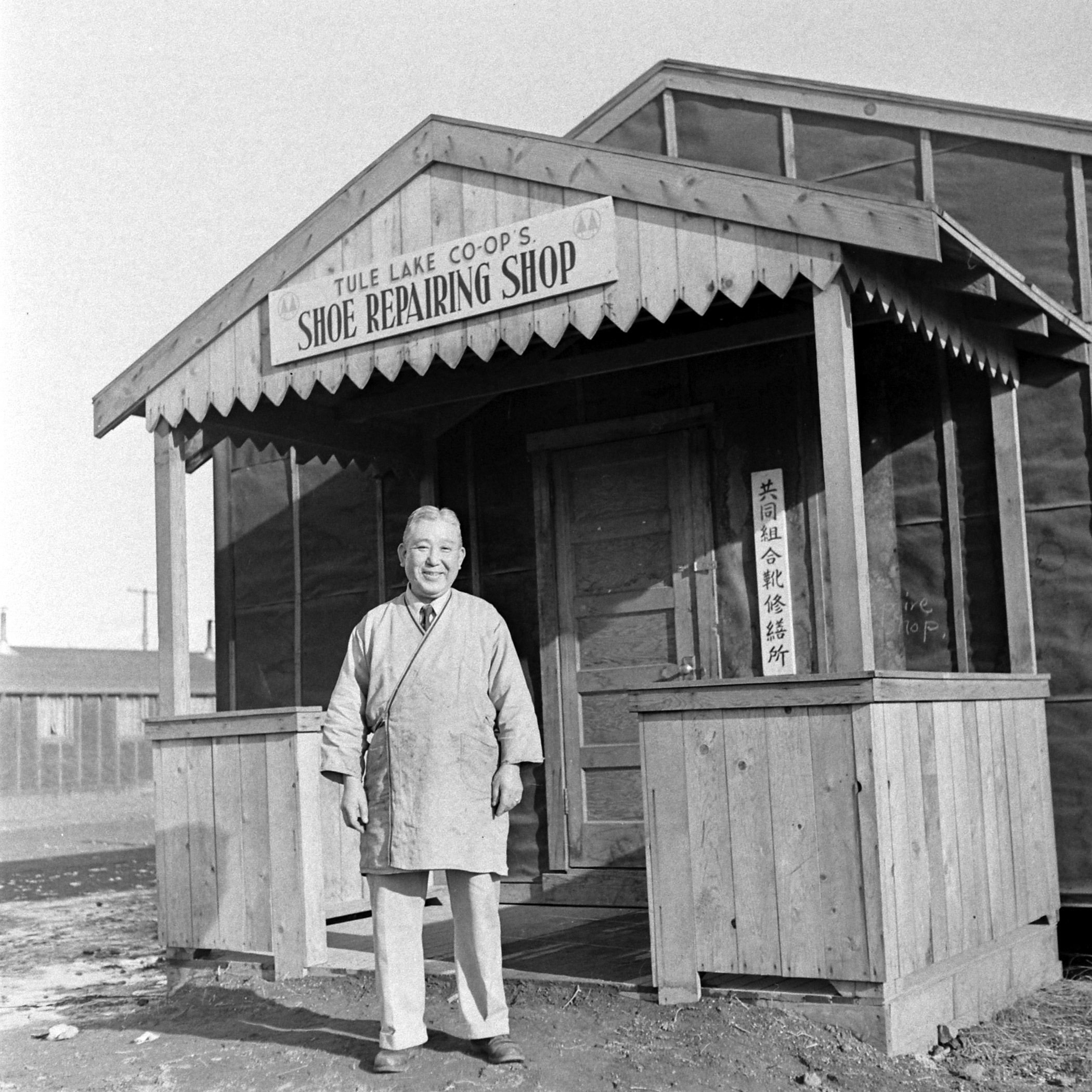

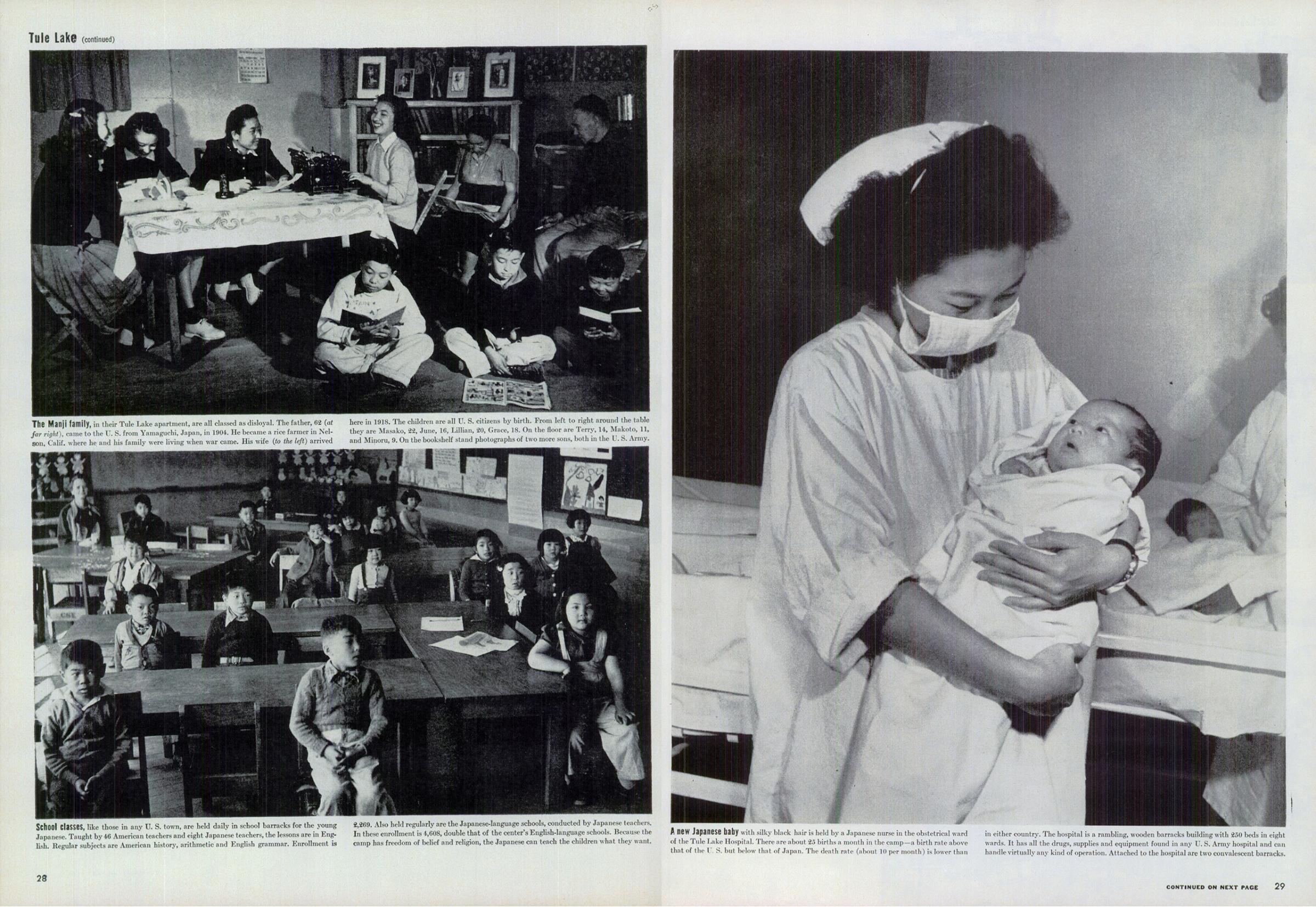

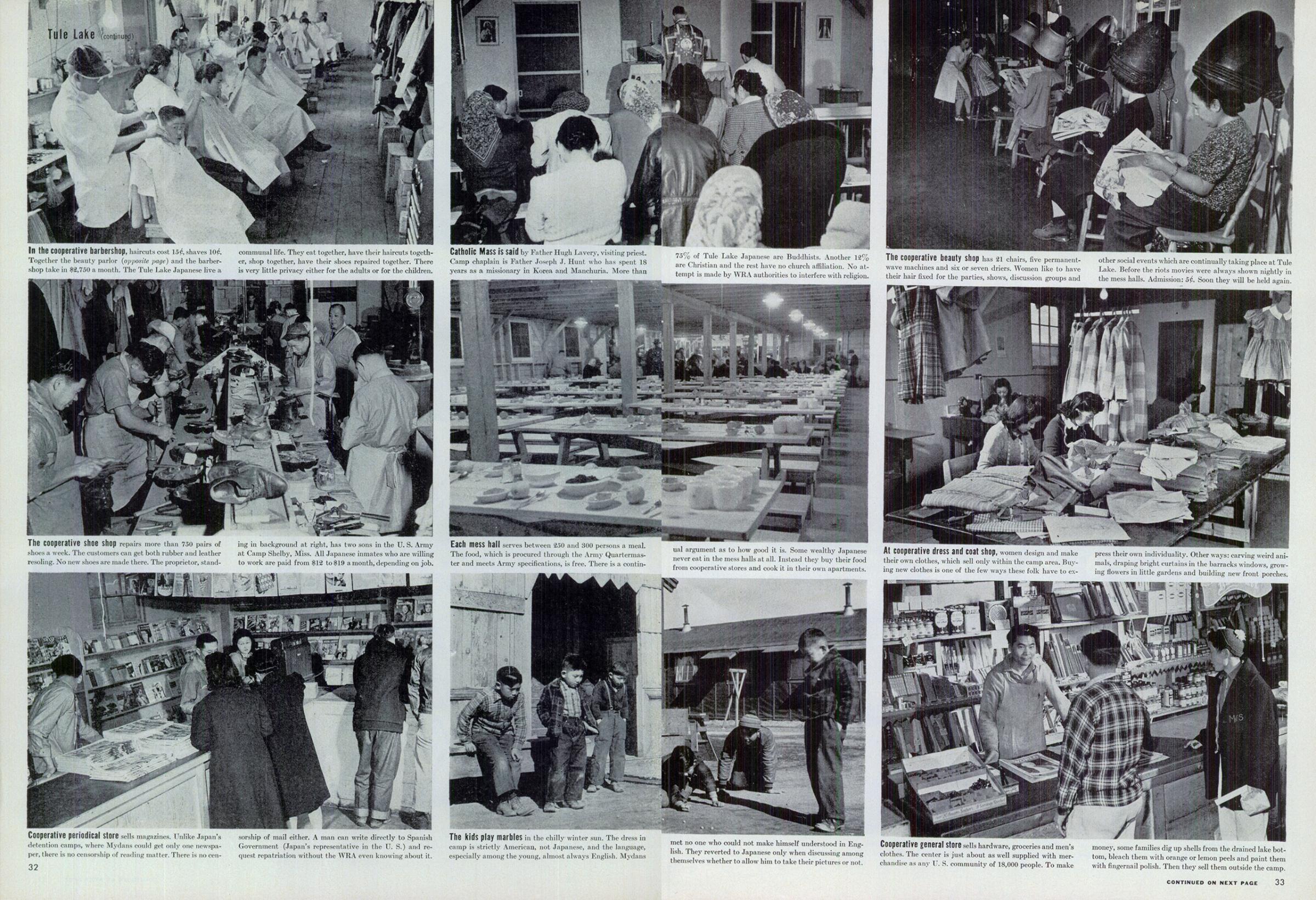

It was later in the 1980s, after Congress established a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, that the public learned the grisly details of the relocation process and life inside the camps, as internees testified at public hearings.

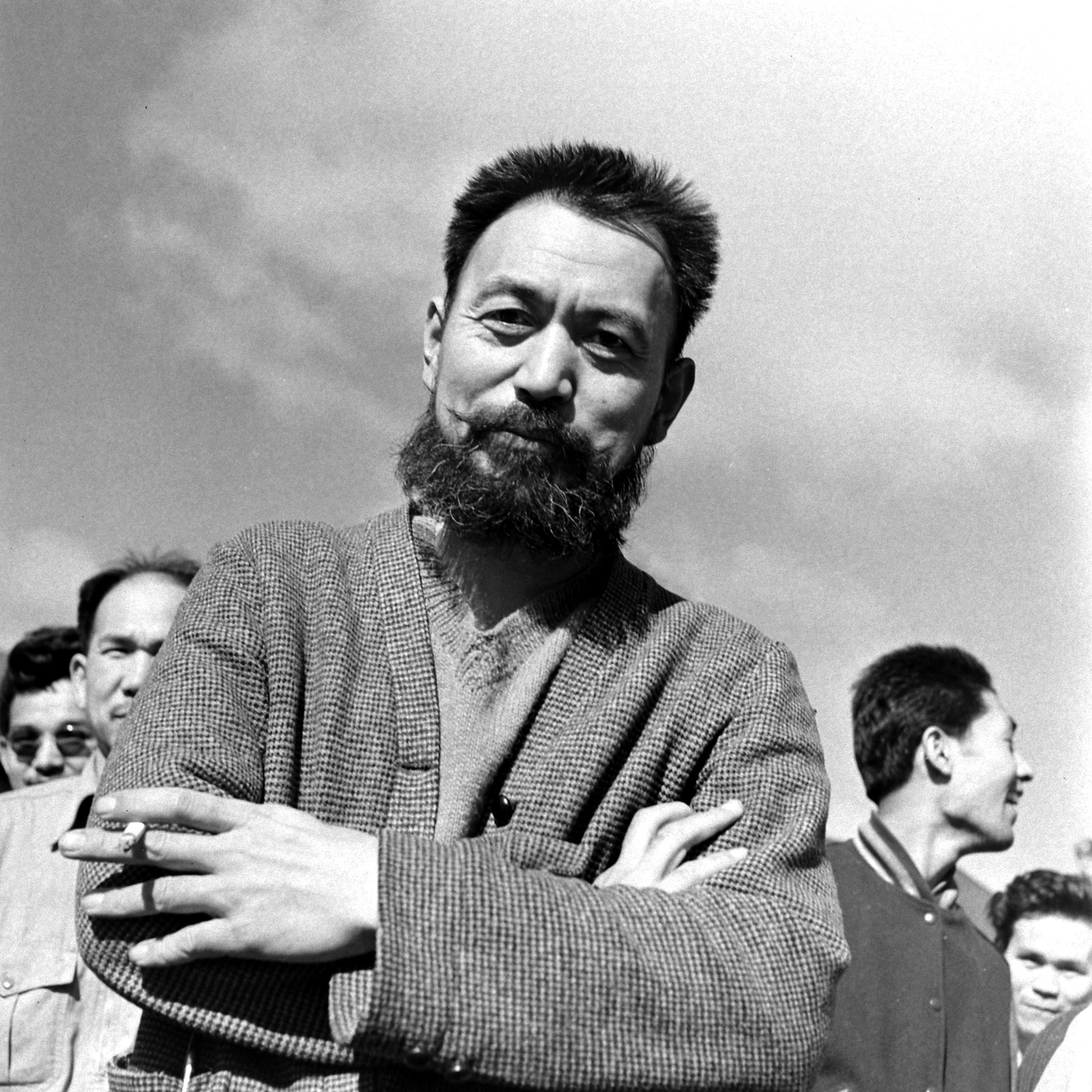

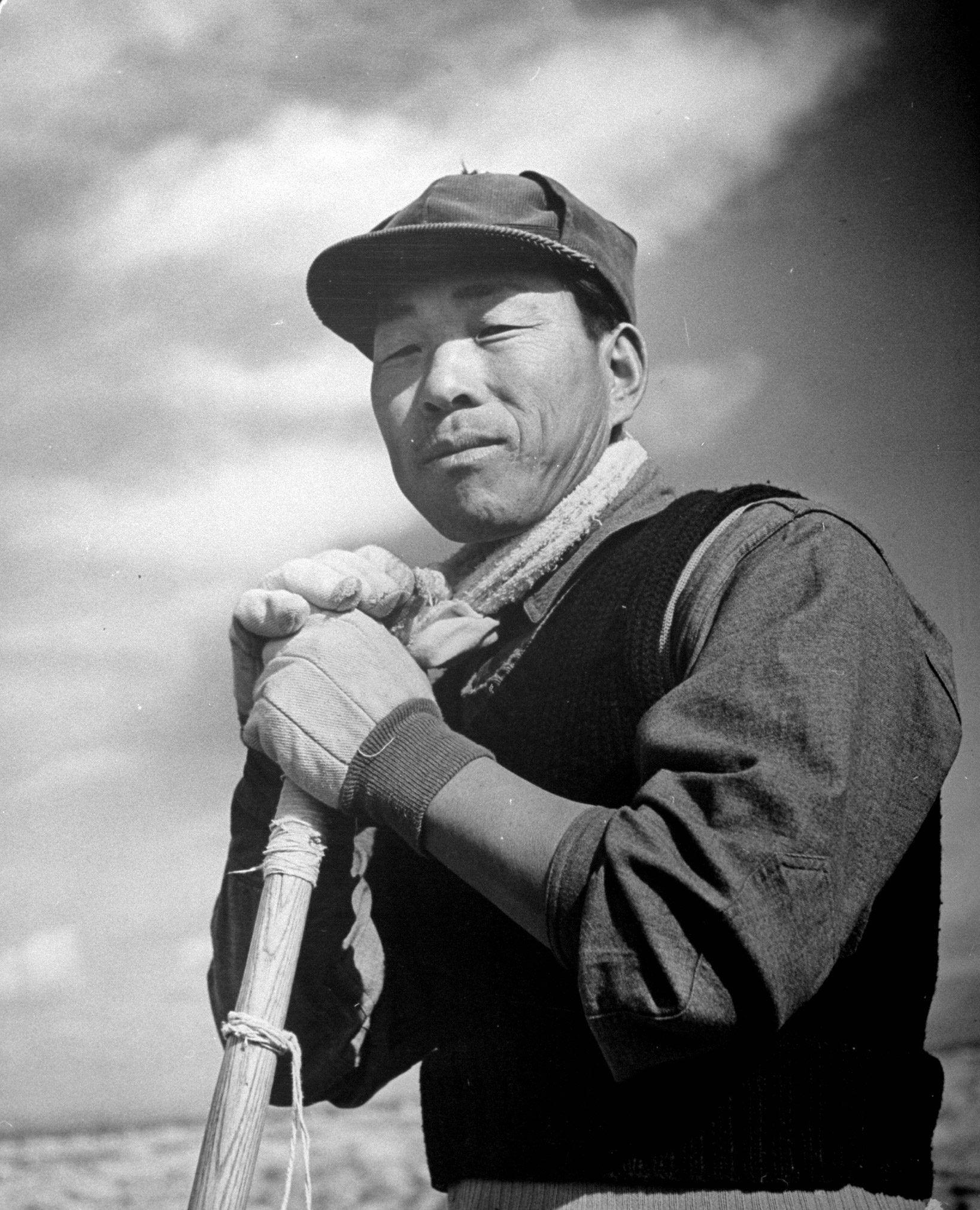

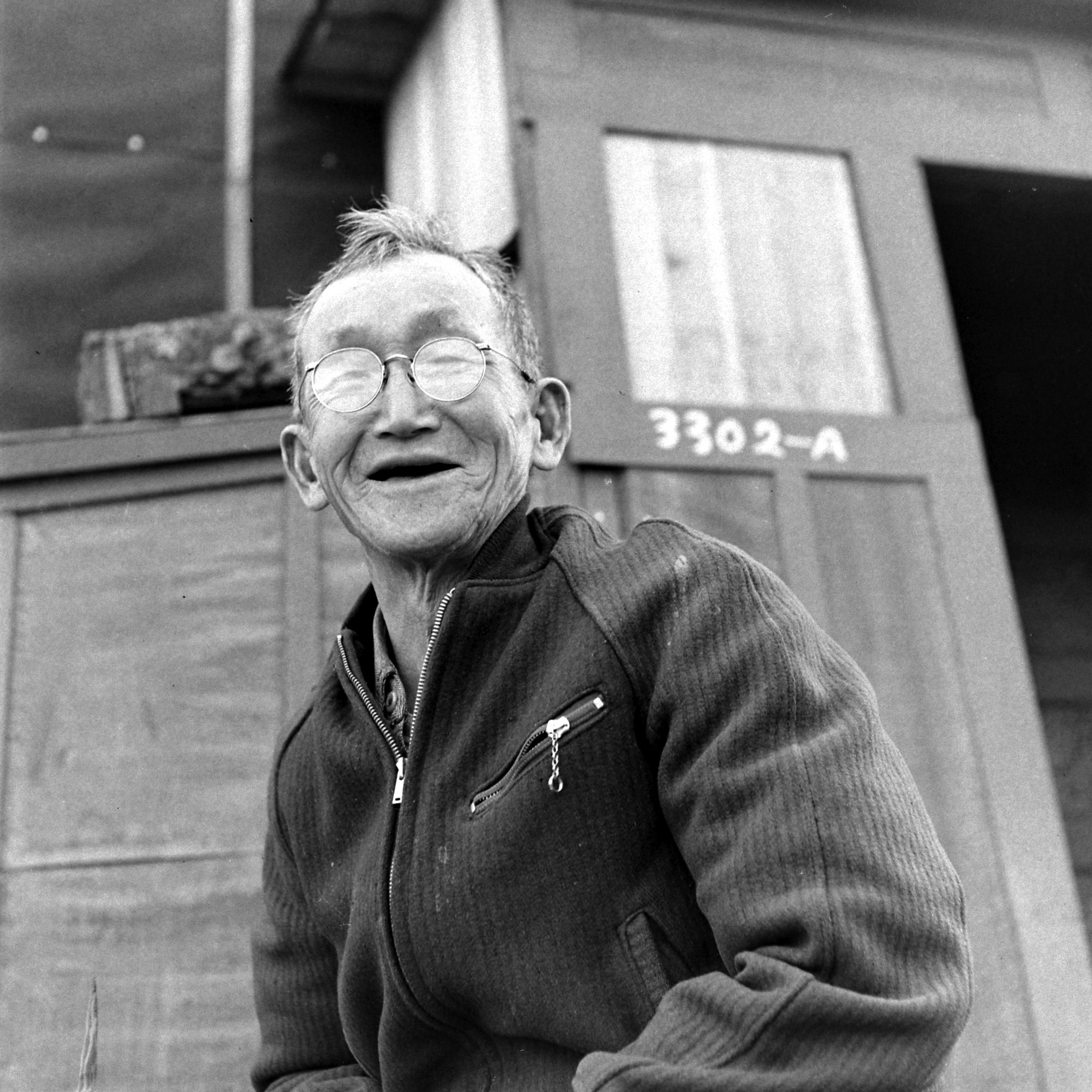

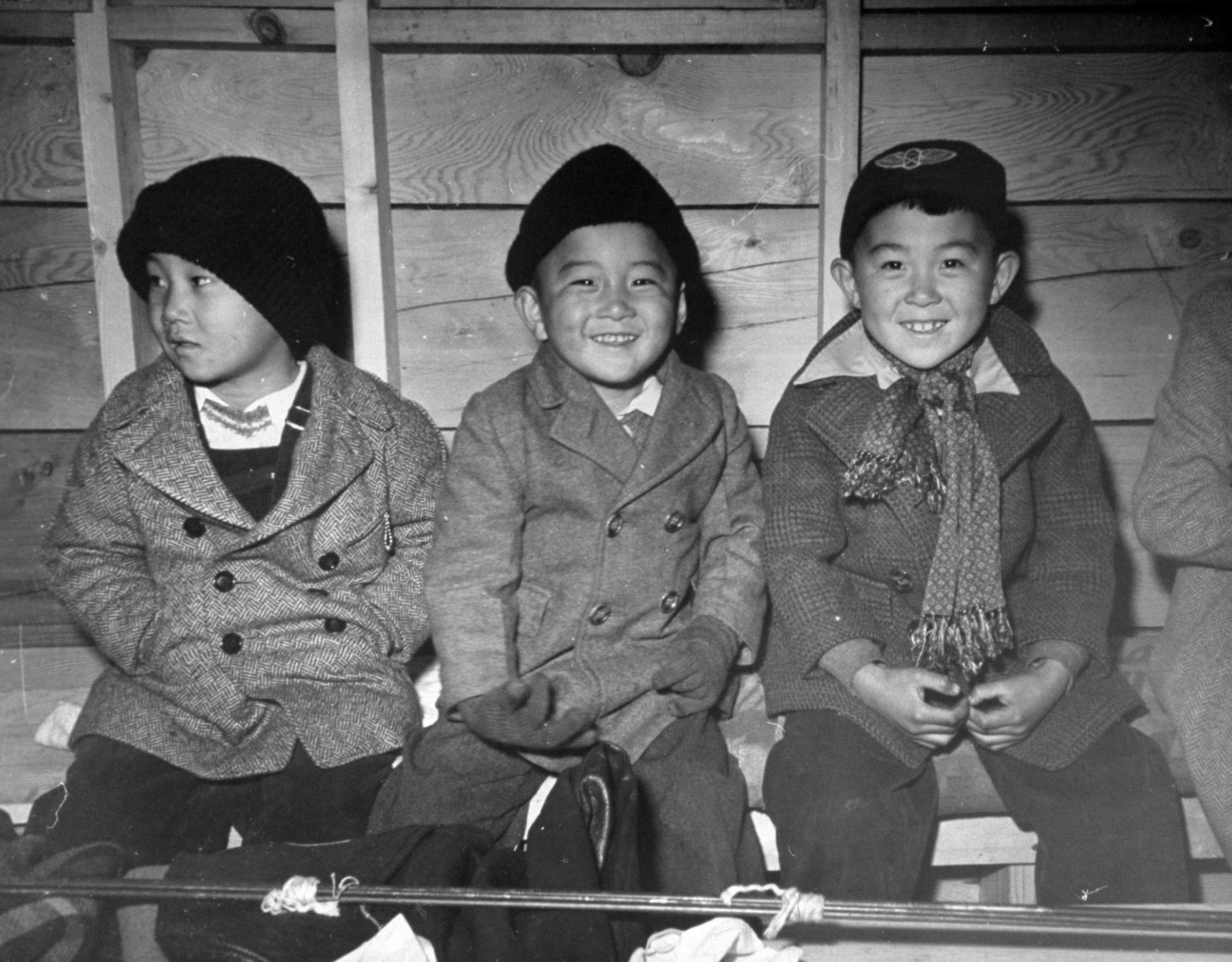

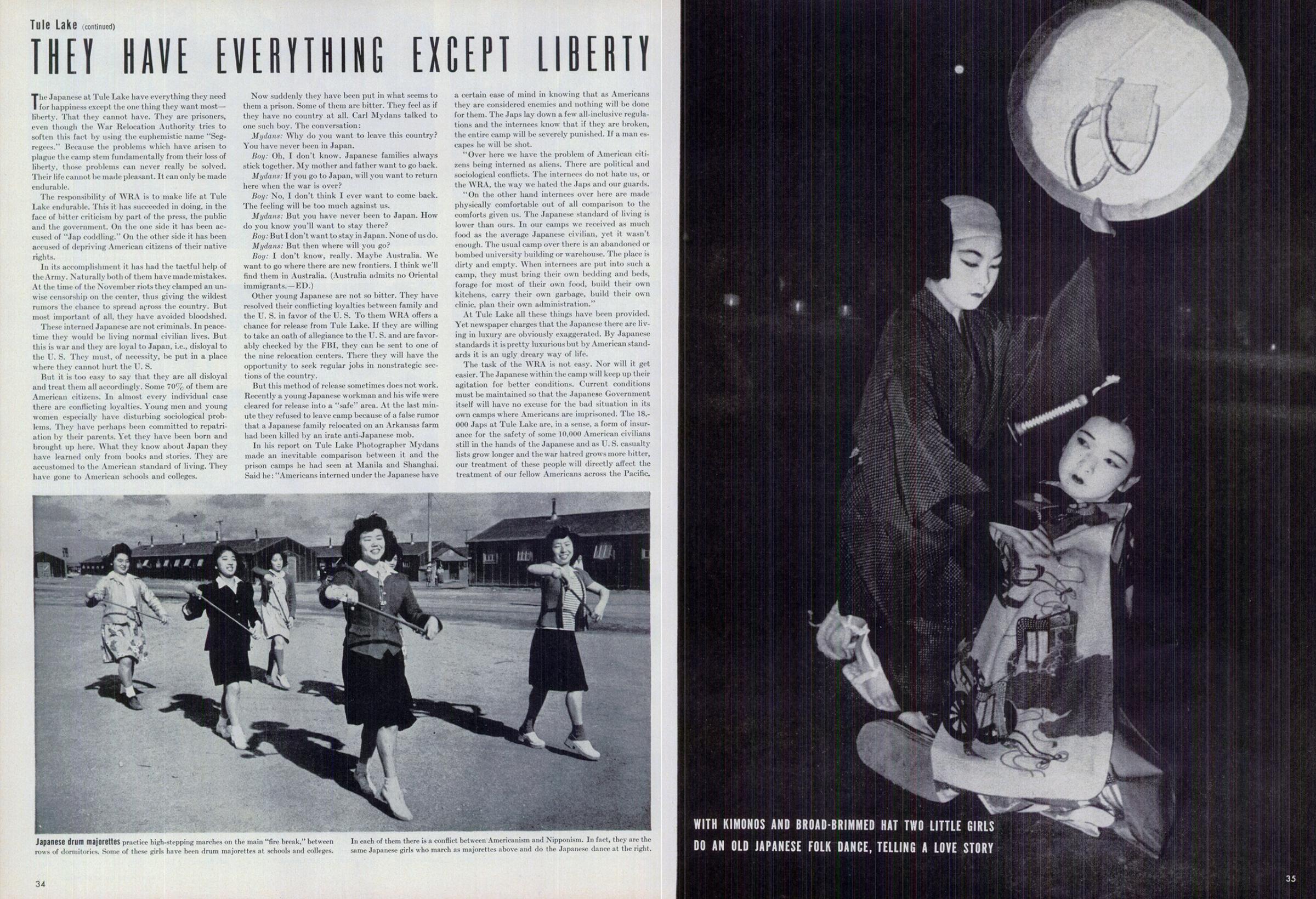

See Striking Portraits From a Japanese Segregation Camp in 1940s California

A turning point came when Peter Irons, a political scientist at the University of California at San Diego, obtained key documents through a Freedom of Information Act request. The records detailed an internal investigation revealing that the federal government knew that Japanese-Americans weren’t actually a national security threat at all. In one document, “FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover stated that he could find no evidence to support the War Department’s contention that West Coast Japanese were signaling Japanese warships off the coast,” according to TIME’s reporting back then.

Those revelations formed the basis of a new case for Fred Korematsu. Nearly 40 years later after the original judgment in his case, he was able to show that the government lied to justify the evacuation. The claim that the internment of Japanese-Americans was justified by security concerns had never been based on serious threats.

In November of 1983, a federal judge in California vacated his conviction. As TIME summed up the legal perspective on both sides, “The Justice Department did not acknowledge any Government misconduct, but decided against fighting the case on the ground that the evacuation program was ‘an unfortunate episode in our nation’s history’ that would best be ‘put behind us.’ U.S. District Judge Marilyn Patel pronounced the Government’s mealymouthed statement ‘tantamount to a confession of error.’ She added that the Supreme Court’s decision was ‘based on unsubstantiated facts, distortions and misrepresentations.'” Though the Supreme Court precedent technically still stands, Korematsu was effectively overturned.

Five years later, more than four decades after one of his predecessors signed the original order, President Reagan signed the official apology.

And that apology was about something bigger than one moment in time. As Congress drafted the legislation for the apology in the spring of 1988, TIME noted, “The country is also apologizing to itself for trampling its own core values.”

Ngai notes that there are some key differences between situation today and how Japanese-Americans were detained during World War II, but she says she sees value in Bush’s having drawn the connection. After all, a lesson that took 40 years to be confirmed is one that ought not be forgotten quickly.

“I don’t think it’s an exact analogy,” she says. “In general children were not taken from their families in the camps. The families were kept together. But I think the extent to which Mrs. Bush is pointing to a racially motivated attack on people’s human rights, that’s certainly valid. Good for her.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com