The dates most Americans remember (July 4, 1776, for example) work as shorthand for signal events. Change takes place across decades, but individual moments remind us what came before and how we got to where we are. So, with Americans celebrating their country at a time of widespread disagreement about what it stands for, TIME asked 25 acclaimed experts in U.S. history to nominate moments that resonate now — moments that just might serve as the mnemonic devices the nation seems to need. Some of their picks are among the most famous days of the past centuries and others are far less famous, but all are relevant today.

Here, they explain their choices.

Explorers Bridge the Pacific (1564-5)

The first successful voyage across the Pacific Ocean — from the Americas to Asia and back — occurred in 1564 and 1565. Barely two generations after Columbus’ more famous voyage, European explorers faced an ocean that was roughly twice as large as the Atlantic and extremely difficult to navigate. This epic passage established a transpacific link, and no other shipping route has been more successful or lasted longer. Trade brought the continents together and created a seascape around the Pacific basin that included places like Acapulco, Manila and the coast of California. By the 18th and 19th centuries, American merchants built on these existing connections to launch their own commercial ventures into the Asia-Pacific region, a process that continues today — even as Washington engages in a trade war with China.

Andrés Reséndez is a professor of history at the University of California, Davis, and winner of the 2017 Bancroft Prize in American History and Diplomacy for The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America.

Read more about the pivot to the Pacific here on TIME.com

Georgia Law Takes Cherokee Land (Dec. 20, 1828)

In 1828, following the discovery of gold on Cherokee land, the Georgia legislature passed a law extending its jurisdiction over the Cherokee Nation and allowing state surveyors to assess and divide land occupied by Cherokee people. The land was then redistributed — with buildings intact — to white residents via a lottery system, driving Cherokee leaders and their white allies to bring suit against the U.S. government. But, when the U.S. Supreme Court found that Georgia had no authority over the Cherokee government or its populace, President Andrew Jackson refused to enforce the decision. Georgia’s coup flouted the law of the land with tacit support from the president, setting the stage for the federal Indian Removal Act of 1830, which mandated the forced relocation of Native peoples—a cautionary tale about the refusal of a president to respect the courts and the failure of the nation’s leaders to protect the rights of indigenous people.

Tiya Miles is the Mary Henrietta Graham Distinguished University Professor of African American Women’s History at the University of Michigan and author of The Dawn of Detroit: A Chronicle of Slavery and Freedom in the City of the Straits, winner of the Merli Curti Social History Award and the James A. Rawley Prize in the history of race relations.

Read more about Andrew Jackson here on TIME.com

J. Marion Sims Opens His Hospital (1844, Date Unknown)

Dr. James Marion Sims, a pioneering American gynecologist, is often credited with establishing the country’s first women’s hospital in Manhattan in 1855 — but in fact the Woman’s Hospital in the State of New York was not the first such institution he opened. In 1844, Sims had his slaves build a women’s hospital in Mt. Meigs, Ala., expressly for experimenting on enslaved women who suffered from a common gynecological condition caused from childbirth injuries. Sims’ surgical work in Alabama — performed with the assistance of other enslaved patients, whom he trained as nurses — helped to launch his career as one of the country’s most famous gynecologists. Even after Sims’ death in 1883, the Mt. Meigs hospital was still being used to treat the black population there. Historical retellings of the rise of American gynecology long overlooked the field’s intimate connection to American slavery. Today however, protests emerged over Sims’ experimentation on enslaved women and his Central Park statue has been removed to his gravesite.

Deirdre Cooper Owens is an associate professor of history at Queens College, CUNY and the Director of the Program in African American History at the Library Company of Philadelphia. She is the author of the Darlene Clark Hine Award-winning book Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology.

Read more about J. Marion Sims here on TIME.com

The Oregon Treaty Defines the Canadian Border (June 15, 1846)

The Oregon Treaty established the United States-Canada border, west of the Rocky Mountains, at the 49th parallel. In the decades prior to the treaty, the U.S. and Great Britain had jointly occupied the region — but, while the boundary settled imperial questions, it also disrupted Indigenous homelands and people. In this way, it was not unlike other North American boundaries established by imperial powers without consultation from Indigenous groups. Today, this region offers examples of successful co-occupancy that reflect the dynamic past.

The U.S. gained extensive natural resources from the 1846 treaty, including the Columbia River, but it now co-manages the waterway with Canada. The two countries are currently modernizing their agreement to reflect contemporary priorities. Meanwhile, during the last decade, the Colville Confederated Tribes of Washington state have successfully fought for recognition of ancestral subsistence rights in British Columbia, reinforcing Indigenous perseverance despite national borders. Through these practices, we witness continuity across the span of history.

Laurie Arnold, an enrolled member of the Sinixt Band of the Colville Confederated Tribes, is an associate professor of history and director of Native American Studies at Gonzaga University, and chairs the American Historical Association’s Committee on Minority Historians. She is the author of Bartering with the Bones of Their Dead: The Colville Confederated Tribes and Termination.

Read more about 1846 here in the TIME Vault

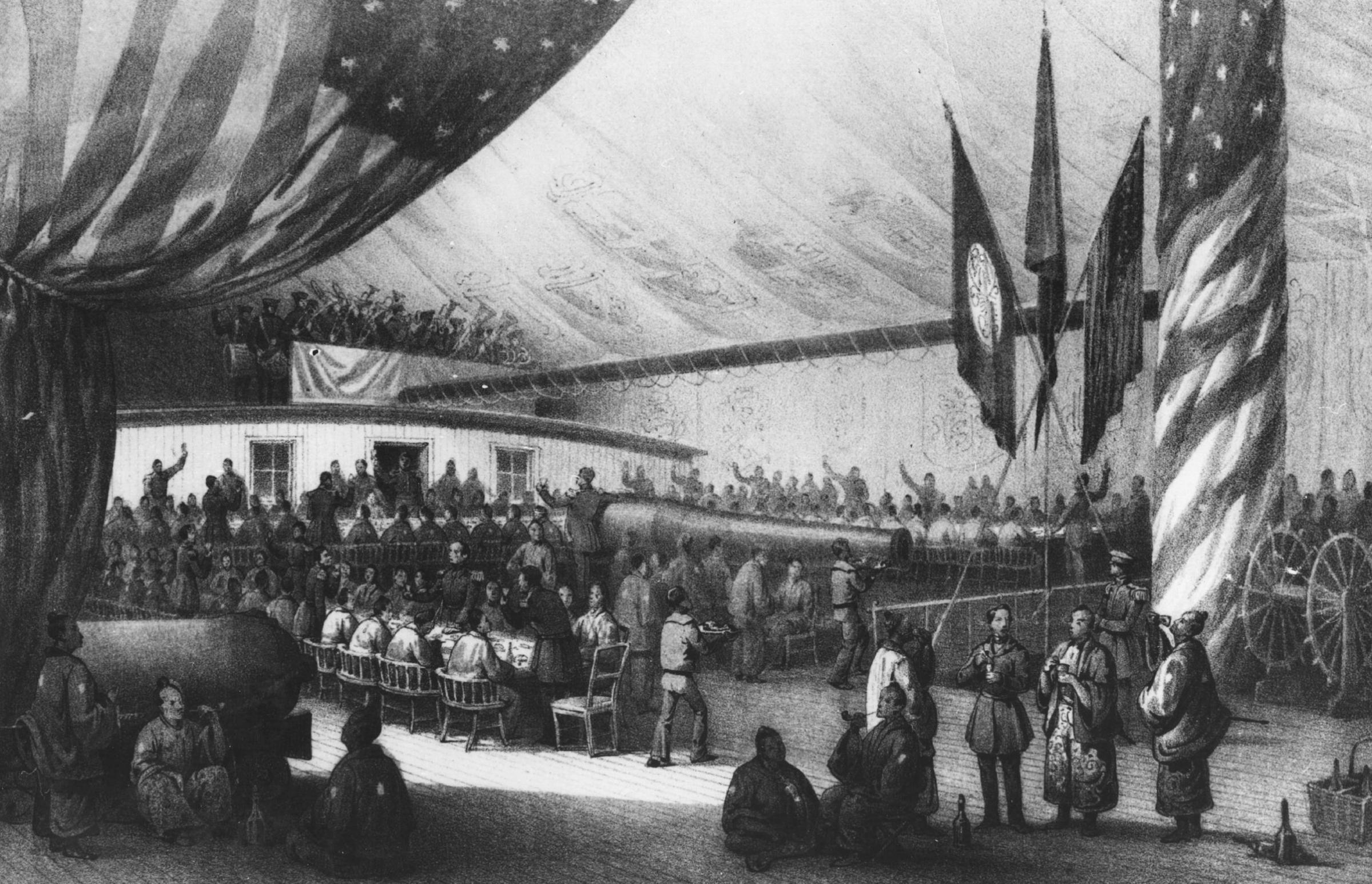

Commodore Perry Reaches Tokyo (July 8, 1853)

On July 8th, 1853, defying Japanese restrictions on international traffic, Commodore Matthew Perry sailed his steam-powered ships into Edo (Tokyo) Bay, heavily armed and belching smoke. Although his exercise in “gunboat diplomacy” culminated in the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa, establishing trade relations between the U.S. and Japan, Perry deserves less credit for changes in Japanese foreign policy than he has received. Other factors were already in play — he arrived amid the disintegration of the Tokugawa government and simultaneous European commercial overtures — and Perry approached Pacific diplomacy with arrogance and contempt. His insistence that the Japanese trade with the United States hinged on a belief that international commerce was a marker of civilization. He had no sense that military enforcement of this norm diminished its value, or that of the numerous American manufactures he brought as gifts. A missionary who accompanied the trip as an interpreter noted wanly that among those gifts, the six-shooters bestowed by Samuel Colt were likely to be particularly appreciated given their potential to repel foreign aggression.

Courtney Fullilove is an associate professor of history at Wesleyan University and author of The Profit of the Earth: The Global Seeds of American Agriculture, an honorable mention for the 2018 Frederick Turner Jackson Award from the Organization of American Historians.

Read more about U.S.-Japan relations here in the TIME Vault

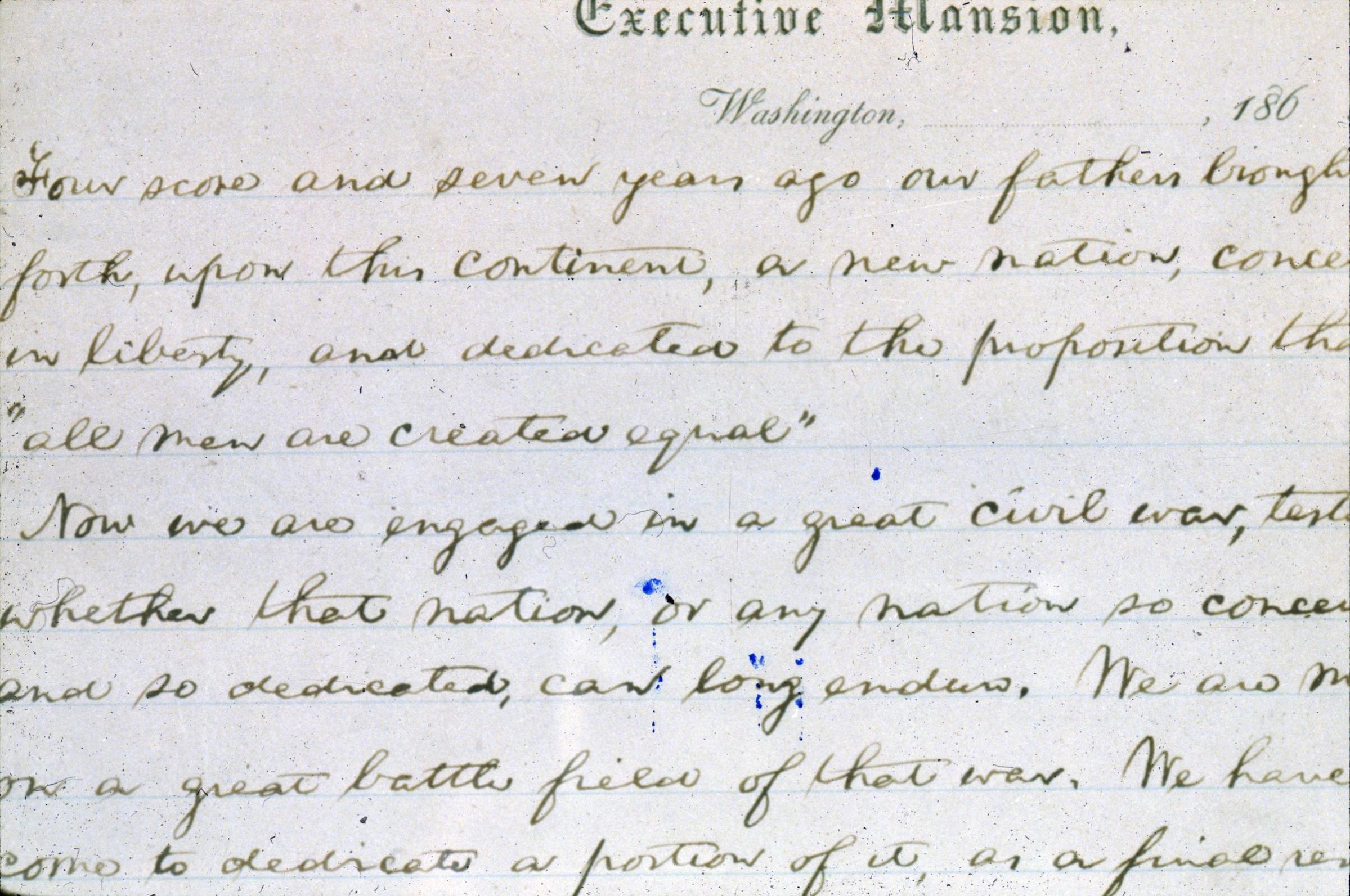

Abraham Lincoln Reminds America of Its Founding Principles (Nov. 19, 1863)

When Abraham Lincoln dedicated a national cemetery for the soldiers who had died at Gettysburg, four months after that central battle of the American Civil War, he was not the principal speaker. But no other speech that day has been remembered the way Lincoln’s words are. He spoke of the past, of the “proposition that all men are created equal” on which the Republic was founded; he spoke of the present, of the sacrifices ordinary men in blue had made to vindicate that proposition; and he spoke of a future in which living Americans must continue to dedicate themselves to the “great task” of preserving that ideal forever. Nothing else anchors the challenges of our present to the intentions of our past more clearly than the Gettysburg Address. Whatever else changes in American life, that proposition does not change; and holding it close is the best guarantee that democracy will endure.

Allen C. Guelzo is Henry R. Luce Professor of the Civil War Era and Director of Civil War Era Studies at Gettysburg College, James Madison Program Garwood Visiting Professor at the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University, and a 2018 Bradley Prize winner. He is the author of Reconstruction: A Concise History.

Read more about the Civil War here on TIME.com

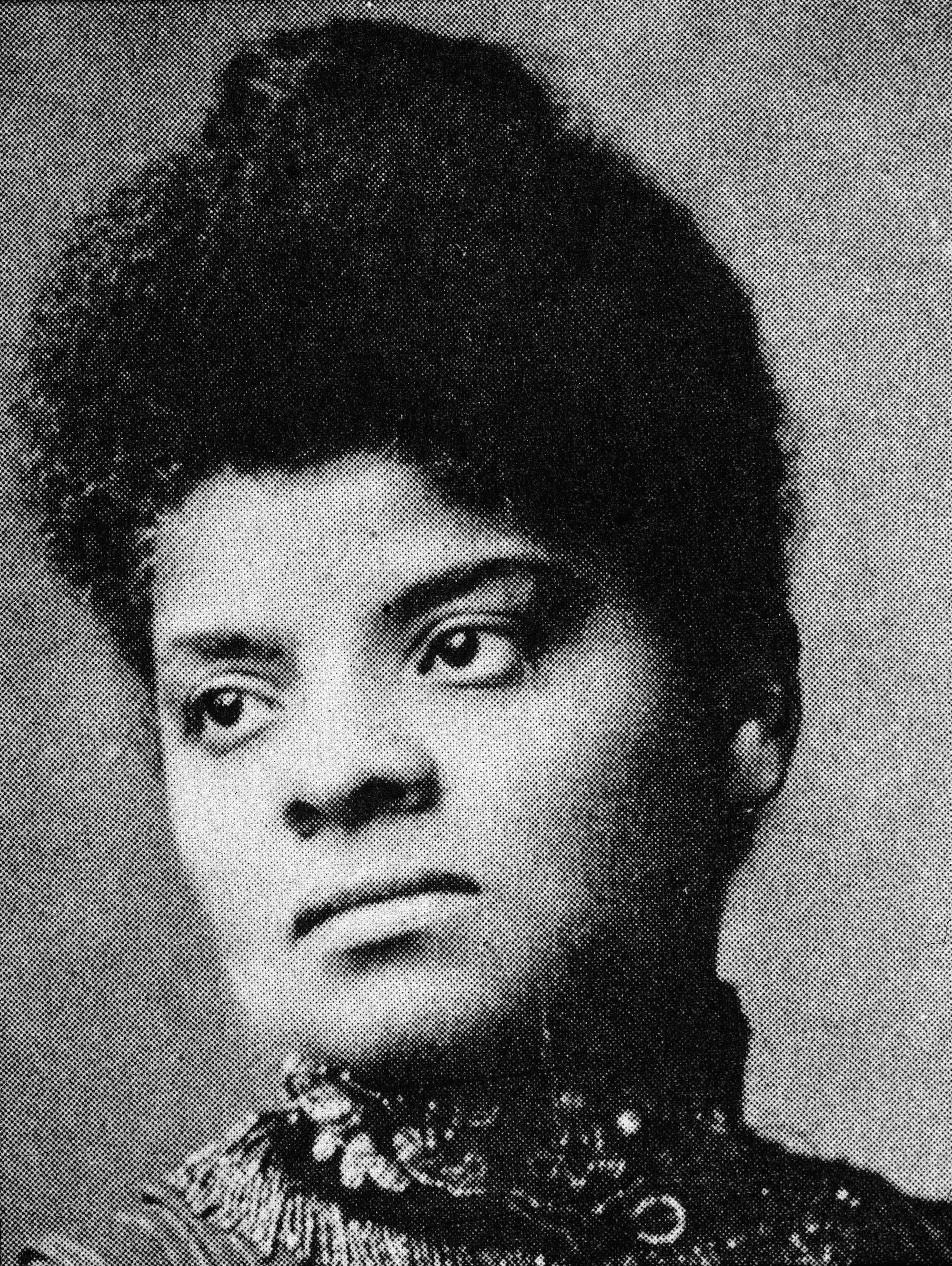

Ida B. Wells Releases Southern Horrors (Oct. 26, 1892)

Four years before the Supreme Court made segregation the law of the land in Plessy v. Ferguson, Ida B. Wells could see — as most Americans could — that there would be little enforcement of the civil rights laws that had been passed in the wake of the Civil War. After three of Wells’ friends were murdered by a lynch mob in Memphis, she knew she could not remain silent. So, she methodically, meticulously and forcefully called out the country that was not living up to its ideals of “liberty and justice for all.” For far too long, we have pushed aside this disturbing chapter of our past. But there is an inspiring story of strength hidden here — one of a woman, far before her time, who used her voice in a way that sent shockwaves across the country and galvanized change. The National Memorial For Peace and Justice opened its doors this April, and in it are 4,400 names of victims lost to the lynching that Wells protested in 1892. I had never heard of Wells before graduate school — never studied lynching in American history, either. Today, I make sure every single one of my students knows her name and studies her work.

Sara Ziemnik of Rocky River, Ohio, was named 2017 National History Teacher of the Year by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Read more about Ida B. Wells here on TIME.com

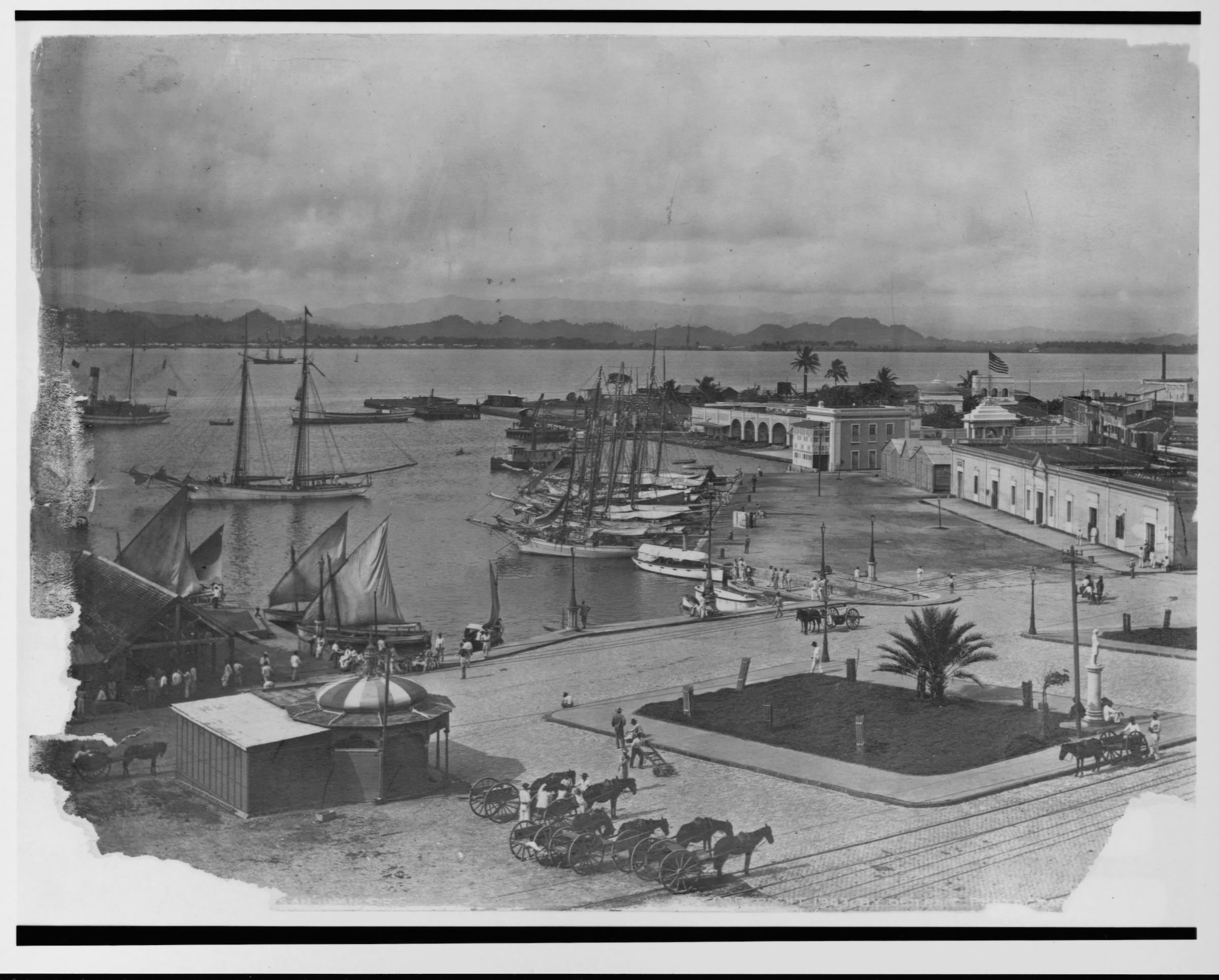

The Supreme Court Sets Puerto Rico Apart (May 27, 1901)

The 1901 Supreme Court case Downes v. Bidwell was one of several cases that decided how the United States would govern the new territories, including Puerto Rico and the Philippines, it acquired in 1898 after the Spanish American War. Many people at the time believed that, because the islands’ residents were racially unfit for citizenship, the territories could never become states and thus could not be governed like other territories, which historically had all been destined for statehood. Normally the Constitution requires uniformity — the federal government can’t make different tax, trade, criminal, or immigration laws for different states or territories. For the first time, Downes v. Bidwell determined that the Constitution does not necessarily follow the flag. The majority opinion famously stated that Puerto Rico was “was foreign to the United States in a domestic sense,” and ruled that Congress could keep territories that would never become states, and could govern them with different laws. More than a century later, Puerto Rico’s ongoing debt and infrastructure crisis, amplified in the wake of Hurricane Maria’s devastation, are attributable in part to the territory’s historic legal inequality. Because of cases like Downes v. Bidwell, Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens who live without the full protection of the Constitution.

April Merleaux is an assistant professor of U.S. Foreign Relations & Empire Studies at Hampshire College and winner of the 2016 Myrna F. Bernath Book Award from the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations for Sugar and Civilization: American Empire and the Cultural Politics of Sweetness.

Read more about the history of Puerto Rico here on TIME.com

The Meuse-Argonne Campaign Begins (Sept. 26, 1918)

Although the Meuse-Argonne campaign is little remembered today, it was the greatest U.S. military contribution to World War I and the opening act of the “American century.” The 47 autumn days of brutal fighting claimed 26,277 American lives — making it the deadliest battle in the nation’s history — and left nearly 100,000 doughboys wounded. This sacrifice materially contributed to the collapse of the German army. It earned Woodrow Wilson a major role in crafting the peace that followed. And it demonstrated that the U.S., which had generally avoided great power entanglements, had the will and ability to assume a major role on the world stage by using its vast military, political and economic power to secure its global interests and further the nation’s worldview. But the Meuse-Argonne also highlights the fact that hard-won victories do not always lead to a just and enduring peace — a lesson that is as crucial today as it was back then.

Richard S. Faulkner is the William A. Stofft Professor and Chair of Military History at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, and author of Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I, which received the World War I Association’s 2017 Norman B. Tomlinson, Jr. Prize for the best work of history in English on World War One and the Organization of American Historians’ 2017 Richard W. Leopold Prize.

Read more about the U.S. in World War I here on TIME.com

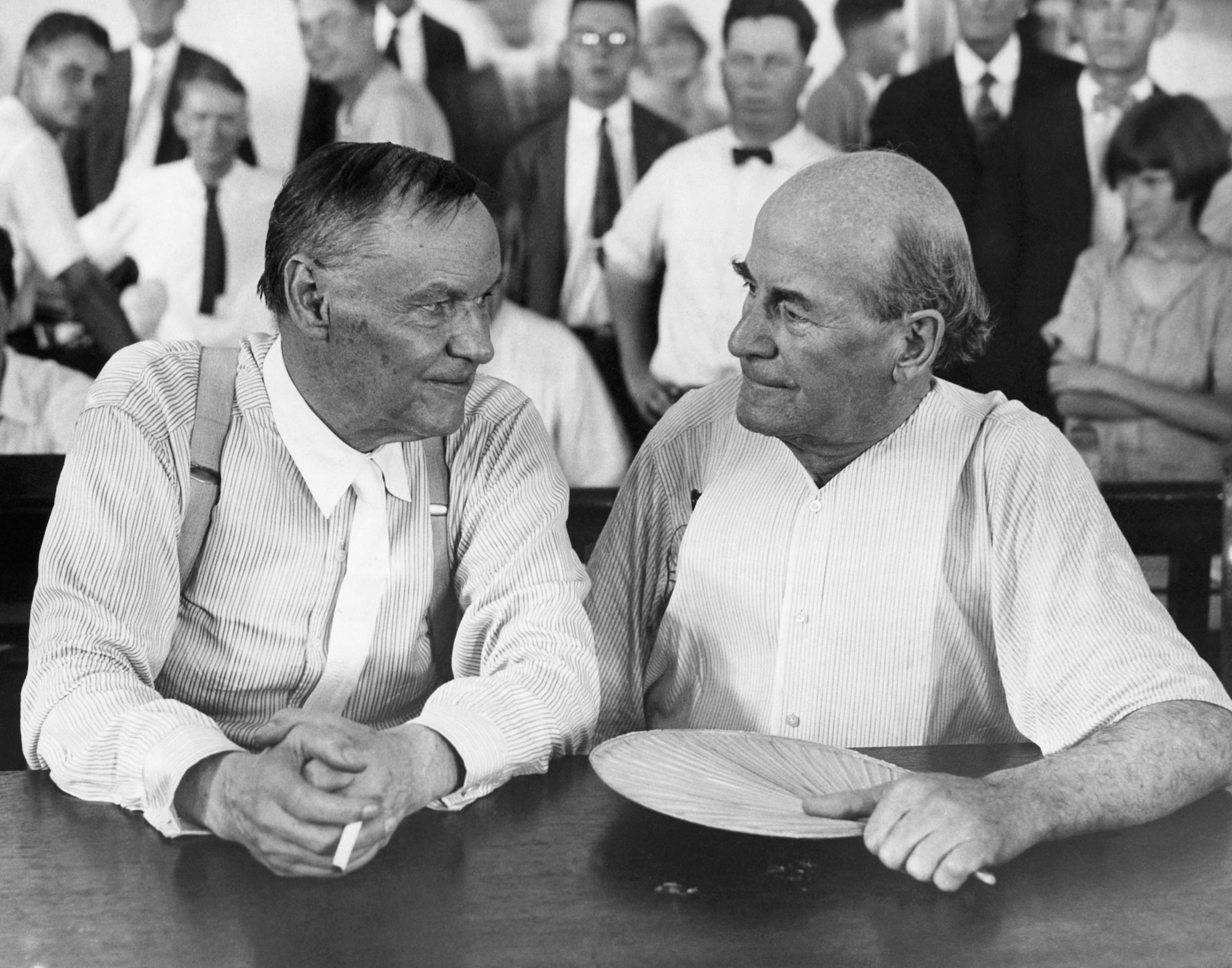

Bryan and Darrow Face Off in the Scopes Trial (July 20, 1925)

When populist politician William Jennings Bryan faced off against attorney Clarence Darrow, it was the highlight of the Scopes trial — a case about teaching evolution in Tennessee that had captured national attention — and the capstone of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy in the Protestant churches. Darrow grilled Bryan on his interpretation of well-known Bible stories. Did he really believe that the whale swallowed Jonah, that Joshua made the sun stand still and that Adam and Eve were the first people? Bryan answered yes, but Darrow made him admit he didn’t know how these things happened and didn’t know any geology or ancient history. The big- city journalists reported that Darrow had revealed Bryan’s ignorance and the absurdity of his biblical literalism. The Great Commoner died five days later, as if the defeat had killed him.

The fundamentalists retreated from battle, dismissed by the rest of society, but flourished under the radar of the press, planting churches from California to Virginia. In 1979, Jerry Falwell surprised everyone by launching a powerful political movement of fundamentalists and other conservative evangelicals. Thirty-seven years later, with white evangelical voters making up more than a quarter of the electorate, the Christian right helped elect Donald Trump.

Frances FitzGerald is a journalist and historian, and winner of the 2017 National Book Critics Circle award for non-fiction for The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America.

Read more about the Scopes Trial here on TIME.com

The Dust Bowl Hits Its Most Infamous Day (April 14, 1935)

When people think about the Dust Bowl, they tend to consider it as a discrete event, something that happened once and will never happen again. It was unique: 1934 was the worst drought in a thousand years of North American history, a time when “rolling dusters” swept across the country, depositing tons of topsoil on Chicago and Washington, D.C. The need to cope with what’s been called the worst man-made ecological catastrophe in our history launched the New Deal, setting the stage for political battles over big government that are still raging.

But now it’s happening again, thanks to climate change. One-hundred-mile wide walls of dust have swept through Phoenix, as severe drought kills grasses and ground cover, leaving soil exposed. It’s a pattern playing out on a planetary scale, sending millions of refugees fleeing sub-Saharan Africa. Scientists now warn that the future may bring a perpetual, global Dust Bowl.

Caroline Fraser is the author of Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Biography and a finalist for the 2018 Mark Lynton History Prize.

Read TIME’s first article to use the term “Dust Bowl” here in the TIME Vault

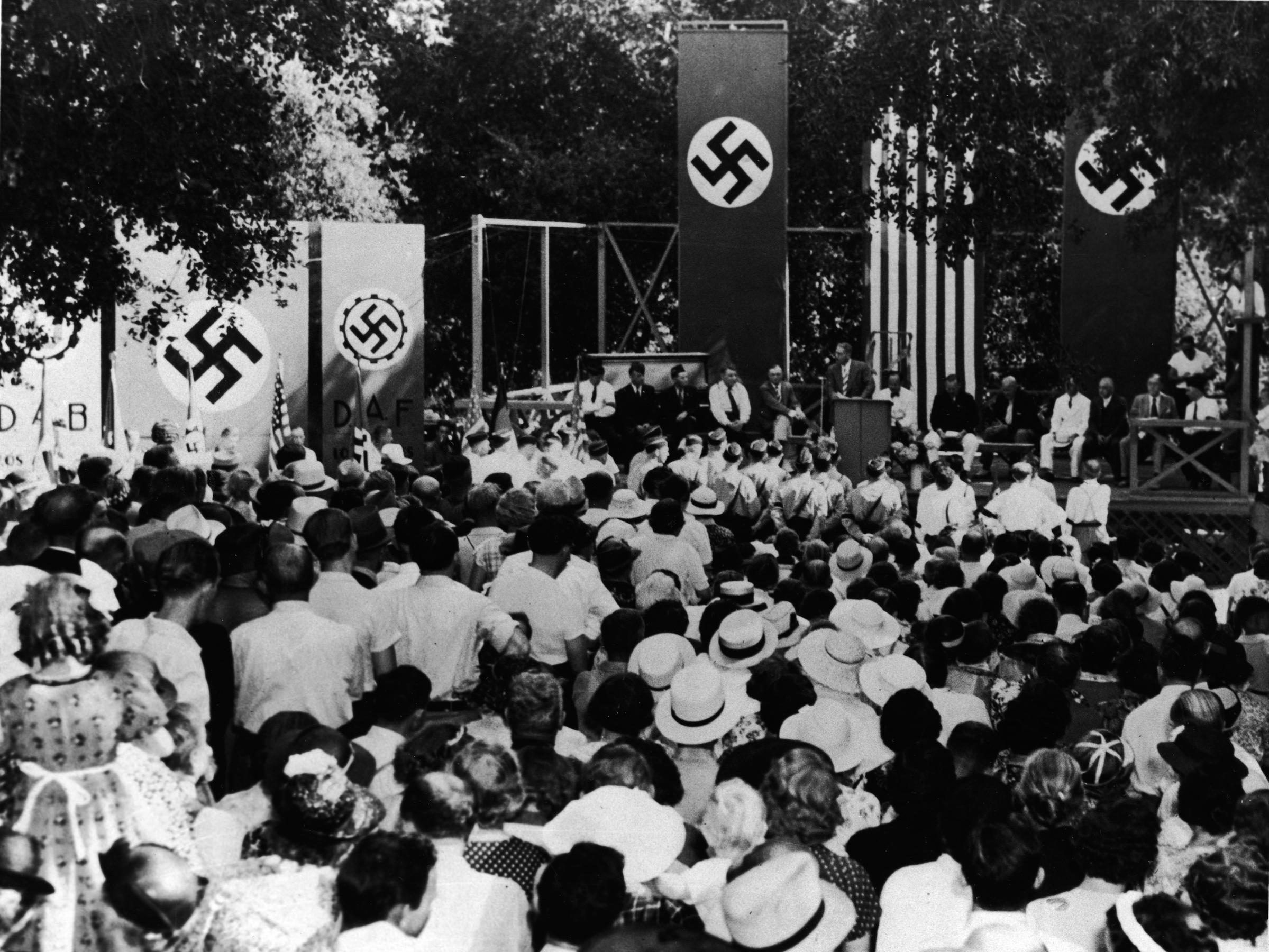

American Nazis Meet in Los Angeles (July 26, 1933)

On July 26, 1933, six months after Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, Nazis in Los Angeles held their first open meeting. These predecessors of the neo-Nazis and white supremacists who marched in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017, prompted Jewish attorney Leon Lewis — who recognized that the government was not doing enough to stem the growth of hate — to recruit a number of World War I veterans and their wives to go undercover within every Nazi and fascist group in Los Angeles, and then report back to him. They did so until the end of World War II. Foiling a series of plots aimed at sabotage and murder, Lewis and his courageous group of spies understood that democracy requires constant vigilance. With their actions they showed that when a government fails to stem the rise of extremists bent on violence, it is up to every citizen to protect the lives of every American, no matter their race or religion.

Steven J. Ross is a professor of history at the University of Southern California and author of Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in History.

Read more about the 1930s hunt for Nazis in the U.S. here in the TIME Vault

The Bald Eagle Gets Federal Protection (June 8, 1940)

![Daniel Mannix [Misc.] Daniel Mannix [Misc.]](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/gettyimages-50521967.jpeg?quality=75&w=2400)

Americans can attribute increased sightings of their national bird largely to the Bald Eagle Protection Act. Congress passed the act in 1940 to check the slaughterous impact of recreational shooters, egg collectors and livestock farmers. Never before had the federal government established protection for an individual species or top predator; the move set a precedent for future wildlife laws, including the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Aggressive enforcement of the Bald Eagle Protection Act, along with listing the bald eagle under the ESA and banning the use of DDT, reversed a population collapse in the lower 48 states after pesticides and habitat loss had reduced breeding pairs to 487 in 1963. With ESA de-listing in 2007 and the Department of the Interior downgrading bird protection this year, the historic act remains the principal legal safeguard for this exclusively North American bird, now thriving nationwide with numbers above 40,000.

Jack E. Davis is a professor of history at the University of Florida and winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in History for The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea.

Read more about the return of the bald eagle here in the TIME Vault

President Truman Orders Racial Equality in the Military (July 26, 1948)

When President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 on July 26, 1948, he acknowledged that racial segregation hampered the U.S.’s military readiness and damaged its standing in the world. The order, which declared, “there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin,” started the slow process of integrating the military at a time when every other national institution save Major League Baseball remained rigidly segregated. Truman also repaid the patriotism African Americans had demonstrated in World War II despite the segregated conditions under which they trained and fought. Blacks had supported the war effort overwhelmingly, but on their own terms. They rallied around the concept of a “Double Victory,” aiming to defeat Nazism overseas and racism at home. Having helped to defeat Hitler, they now had a president on the record saying that Jim Crow had to go. Mass movements for civil rights have ebbed and flowed in the years since, but Truman’s actions proved how much of a difference having a supporter of civil rights for all Americans in the White House could make.

J. Todd Moye is a professor of history at the University of North Texas and president of the Oral History Association. He is the author of Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II.

Read more about segregation in the military here on TIME.com

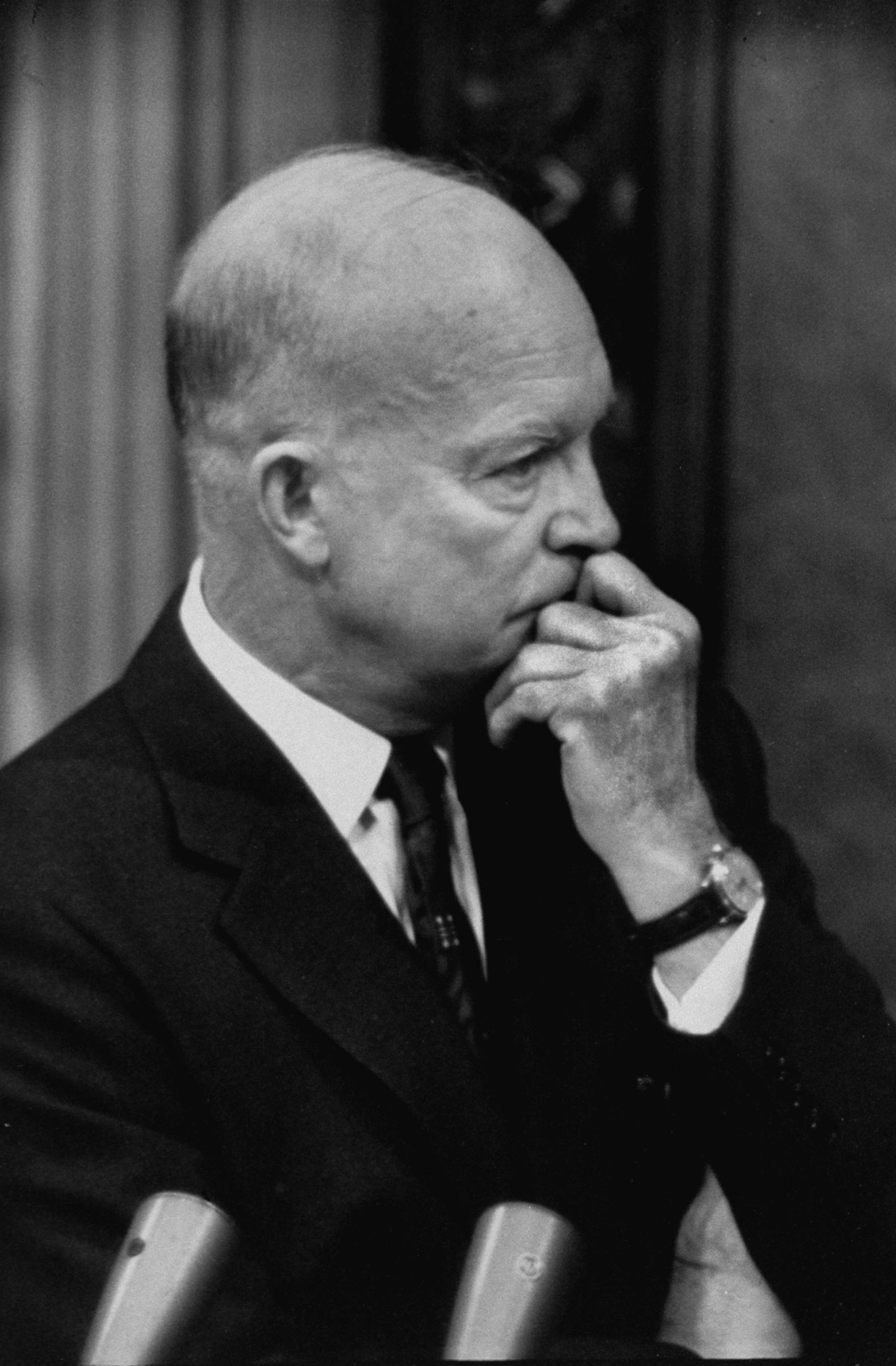

President Eisenhower Effectively Bans LGBT People From Government (April 27, 1953)

President Trump’s recent call to ban most transgender people from serving in the military was not the first time a U.S. president used his position to exclude LGBT people from government service. That dubious honor goes to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, whose Executive Order 10450, issued 65 years ago, included “sexual perversion” — a stigmatizing term for homosexuality — as grounds for dismissal from federal government jobs. Thousands of suspected gays and lesbians lost their jobs. The executive order was part of a broader anti-gay Lavender Scare that accompanied the anti-communist Red Scare of the same era. And it inspired a fledgling gay rights movement, which actively opposed it. The ban on gays and lesbians in the federal civil service was not reversed until 1975. Five years later, President Jimmy Carter endorsed the first major party platform that included a gay rights plank.

Joanne Meyerowitz is the Arthur Unobskey Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University and the president-elect of the Organization of American Historians. She is the author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States.

Read more about LGBT history on TIME.com

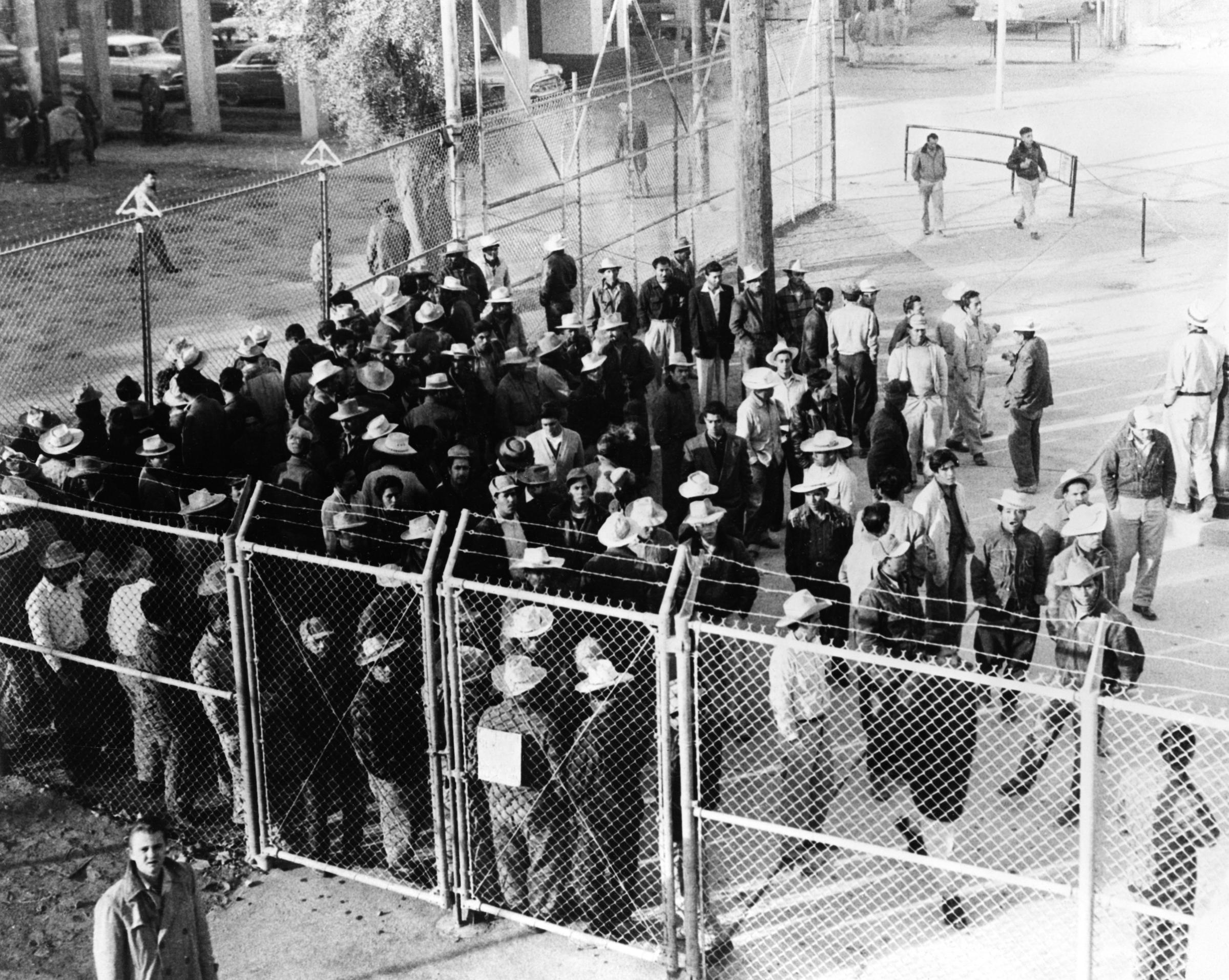

The U.S. Begins Mass Deportation of Mexican Migrants (June 9, 1954)

In 1954, the federal government carried out one of its first mass deportations of Mexican immigrants from the U.S. Operation Wetback, as it was known, ended up separating parents from their children, stranding deportees in the deserts of northern Mexico without food or water, and damaging the U.S.’s reputation at home and abroad. For decades prior, the southwestern borderlands had prospered under a more fluid, humane and practical definition of boundaries, driven in large part by the wants and needs of the blended, binational border communities. In deference to these local interests, the federal government resisted engaging in draconian deportation measures. These reservations fell by the wayside as a wave of anti-Mexican animus, triggered by an economic recession, led the Immigration and Naturalization Service to adopt a highly militarized approach to immigration law enforcement, with Operation Wetback at its center. Since 1954, mass deportations have become so routine that the American public now takes them for granted. We have forgotten that there was a time in U.S. history when the removal of hundreds of thousands of immigrants by the federal government was unthinkable.

S. Deborah Kang is an associate professor of history at California State University, San Marcos, and winner of the Henry Adams Prize from the Society for History in the Federal Government, the Américo Paredes Book Award for Nonfiction, the Theodore Saloutos Book Award from the Immigration and Ethnic History Society and the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians Book Prize for The INS on the Line: Making Immigration Law on the US-Mexico Border, 1917-1954.

Read more about “Operation Wetback” here on TIME.com

Ella Baker Makes a Plea for Black Lives (Aug. 6, 1964)

In August 1964, civil rights activist Ella Baker stated, “Until the killing of black men, black mothers’ sons, becomes as important to the rest of the country as the killing of a white mother’s son — we who believe in freedom cannot rest until this happens.” Baker delivered those words during a keynote address in Jackson, Miss., just days after the discovery of the bodies of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — three civil rights activists murdered earlier that summer. Baker had helped organize the Voter Education Project and “Freedom Summer,” which brought volunteers like Goodman and Schwerner to Mississippi to register voters. (Chaney was from there; he was black and they were white.) After the three men went missing that June while investigating the burning of a black church, the case made national headlines as federal investigators searched for them. But while combing through the area, search teams discovered other bodies too — murdered black Mississippians whose lives had not been considered important enough to warrant a federal investigation.

Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were given posthumous Presidential Medals of Freedom in 2014, but the story of those other morbid discoveries — the inspiration for Baker’s speech — never reached a satisfying conclusion. Her words continue to inspire activists, and especially resonate with the Black Lives Matter movement, built on the premise that the killing of unarmed black Americans should trouble everyone, regardless of their race.

Tyina Steptoe is an associate professor of history at the University of Arizona and author of Houston Bound: Culture and Color in a Jim Crow City, winner of the Kenneth Jackson Award for Best Book of 2016 (North American) from the Urban History Association and the 2017 W. Turrentine-Jackson Book Prize from the Western History Association.

Read more about Ella Baker here on TIME.com

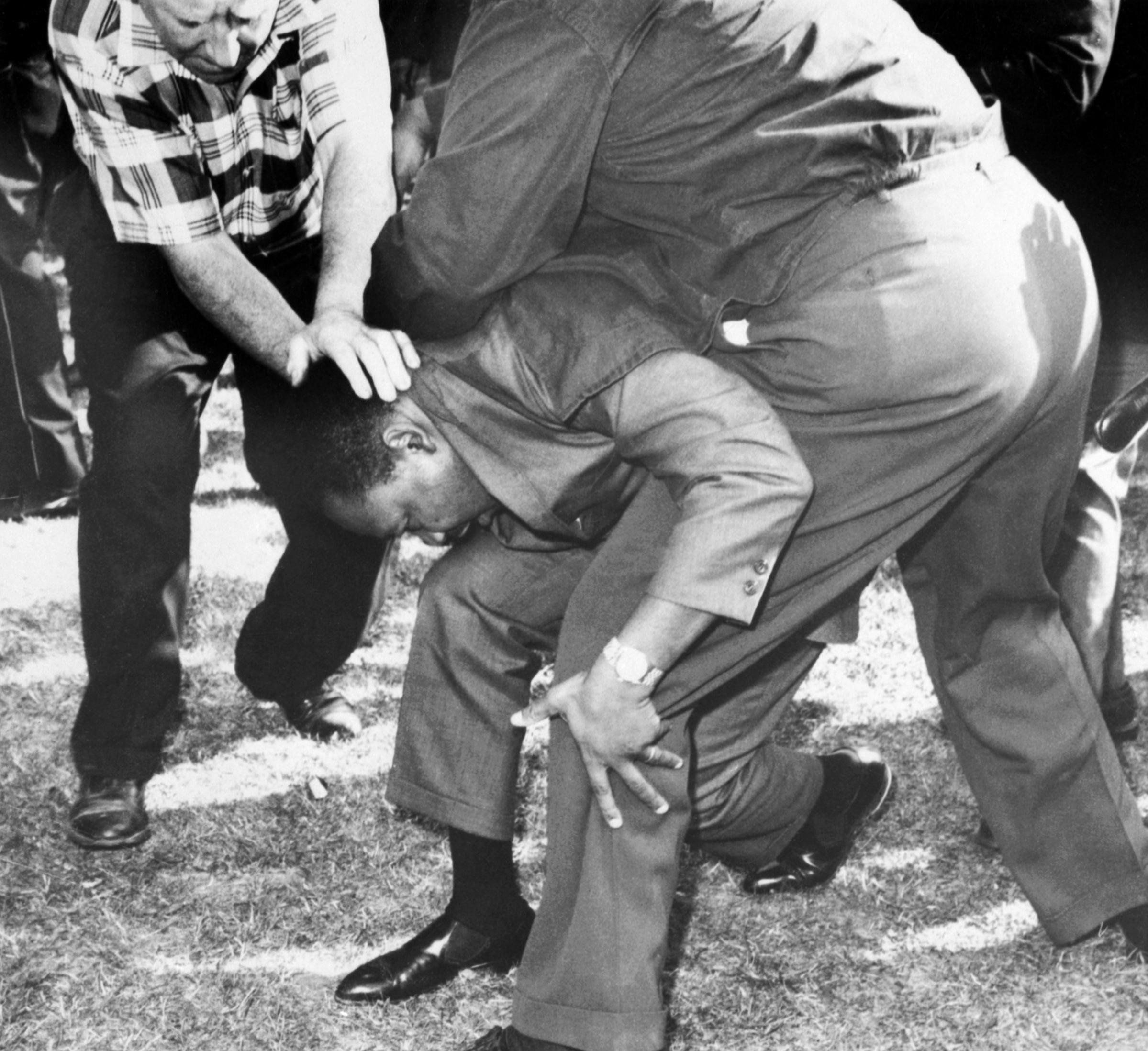

Martin Luther King Jr. Is Assaulted in Chicago (Aug. 5, 1966)

After more than a decade leading the South’s Civil Rights Movement, by 1966 Martin Luther King Jr. had turned his sights toward contesting racial inequality in the North. King saw that millions of black Southerners who had migrated to northern cities like Chicago in search of opportunity had found “not a land of plenty but a lot replete with poverty.” His Chicago Freedom Movement most pointedly challenged discriminatory housing practices that reinforced racial segregation and black poverty. White resistance to the movement’s nonviolent protests was virulent, and King was struck in the head with a rock during one such march. “I can say that I had never seen, even in Mississippi, mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as in Chicago,” he later reflected. The Chicago Freedom Movement fizzled later that year, and the Fair Housing Act passed in the wake of King’s 1968 assassination largely failed to accomplish the movement’s lofty goals, but it threw into sharp relief the extent to which deeply entrenched racial inequalities and animosities were a national problem, not a Southern one.”

Brian McCammack is an assistant professor of environmental studies at Lake Forest College and winner of the Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians for Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago.

Read more about the attack on King here on TIME.com

The Tierra Amarilla Courthouse Is Raided (June 5, 1967)

In a rare instance when minority militancy raced past the realm of rhetoric and toward actual violence, armed Mexican Americans stormed a courthouse in the tiny town of Tierra Amarilla, N.M. Led by a charismatic ex-preacher named Reies López Tijerina, the assailants shot two people and kidnapped two others. They took these extreme actions to bring attention to a piece of U.S. history unfamiliar to most Americans then and now: after the U.S.-Mexico War of 1846-1848 moved the border, Mexican citizens who suddenly found themselves living in the new American Southwest confronted massive land dispossession at the hands of the government and individual Americans. Tijerina’s group was determined to recover their ancestors’ property — and, though they failed to gain a single acre, their courthouse raid exposed, in Tijerina’s words, a “crime that was stinking up the pages of New Mexican history.” Today, at a time of intense immigration debates, the raid also serves to remind Americans that the long history of Spanish-speaking people in the region predates the founding of the nation.

Lorena Oropeza is an associate professor of history at the University of California, Davis, and winner of the 2017 Equity Award from the American Historical Association. She is the author of ¡Raza Sí! ¡Guerra No!: Chicano Protest and Patriotism During the Viet Nam War Era.

Read more about Tierra Amarilla here in the TIME Vault

Nixon Meets Mao (Feb. 21, 1972)

There was no guarantee that the ailing Mao Zedong would meet with Richard Nixon when the U.S. president arrived in Beijing on Feb. 21, 1972. The invitation came suddenly, and after Nixon rushed off with a minimal entourage, those left behind were struck by the thought: Had the enemy just captured the president? Far from it. The planet-shaking photographs of the Red Chinese dictator, gripping the hand of the arch anti-Communist, fulfilled a vision that Nixon put to paper years before, of a day when the tiger economies of Asia would join Europe and America in a new, peaceful computer age — but only if mighty China, freed from seething isolation, came along. The first step was that handshake. Mao offered: “I like rightists.” Answered Nixon: “Those on the right can do what those on the left talk about.” Only Nixon could go to China. It was, like he said, a trip that changed the world.

John A. Farrell is the author of prize-winning biographies of House Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, defense attorney Clarence Darrow, and President Richard Nixon. He has been selected by the New-York Historical Society as the “American Historian Laureate” for 2018.

Read more about the Nixon in China here in the TIME Vault

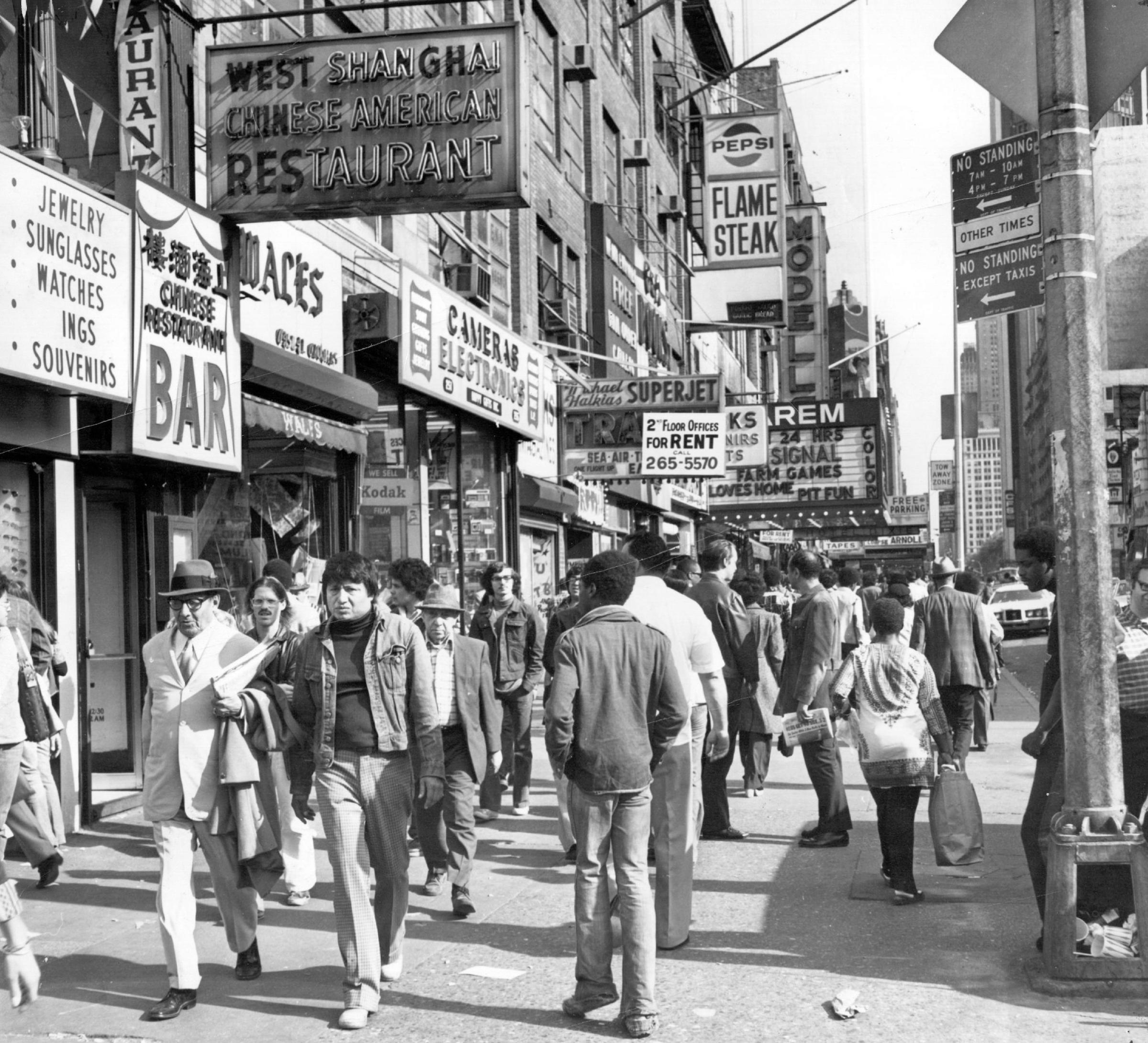

New York City Teachers Go on Strike (Sept. 9, 1975)

As New York City faced near-bankruptcy in the mid-1970s, teacher layoffs caused class sizes to shoot up to 45 or 50 students per class and school staffs were reduced to a minimum. In response, the city’s public school teachers went on strike. The move was greeted with great support by many families, who joined teachers on the picket lines. The strike lasted just one week; it ended in frustration, and many of the issues it raised went unresolved. This strike was reminiscent of those we’ve seen of teachers in “red states” this past spring — people suffering from the low respect and low funding given to public educators and education in our country. Then and now, they are a legacy, in a way, of the politics of austerity and skepticism toward government that New York’s fiscal crisis helped to inaugurate.

Kim Phillips-Fein is an associate professor of history at New York University and author of Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics, a finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in History.

Read more about the teachers’ strike here in the TIME Vault

Ronald Reagan Speaks of the “Welfare Queen” (Campaign season, 1976)

During the 1960s and 1970s, thanks to rising unemployment and inflation, the number of parents receiving welfare had ballooned. It was in this context that in 1976 Ronald Reagan introduced the “welfare queen” into the national lexicon. At almost every stop in his unsuccessful campaign for the Republican presidential nomination, Reagan told crowds about a Chicago woman who got rich off her “80 names, 30 addresses, 12 Social Security cards.” Although his tellings were inconsistent and exaggerated, the story was based on the highly unusual case of Linda Taylor. She was hardly an average welfare recipient — she also posed as a voodoo practitioner and has been linked to a notorious kidnapping — but pundits nonetheless used her story to disparage all woman on public assistance and advance racist stereotypes about black mothers. Sensationalized claims of rampant fraud became a principle rationale for ending welfare and weakening the social safety net. While we hear less about the “welfare queen” these days, exaggerated stories of the abuse of social welfare programs continue to be used to rationalize cuts to social services.

Julilly Kohler-Hausmann is an associate professor of history at Cornell University and author of Getting Tough: Welfare and Imprisonment in 1970s America, an honorable mention for the Frederick Jackson Turner Award from the Organization of American Historians.

Read more about Ronald Reagan’s 1976 campaign here in the TIME Vault

Activists “Invade” Kaho’olawe (Jan. 6, 1976)

On Jan. 6, 1976, eight Native Hawaiian activists and one Native American ally defied the orders of the U.S. military by stepping off boats and onto the Hawaiian island of Kahoʻolawe. Beginning during World War II, American forces had used the island for bombing practice, threatening its ecosystem and obliterating sacred sites — a continuation of the history that dated back to the illegal American annexation of the independent nation of Hawaiʻi in 1898. Landing on Kahoʻolawe was forbidden. But, in the early 1970s, Native Hawaiians were engaging in a wave of activism to defend Hawaiian culture, language and sovereignty. More than 50 people headed to Kahoʻolawe in small boats. Most were intercepted or diverted. Two people died at sea. The nine who made it (Walter Ritte, Emmett Aluli, Kimo Aluli, George Helm, Gail Kawaipuna Prejean, Stephen K. Morse, Ellen Miles and Ian Lind, as well as Karla Villalba of the Muckleshoot Nation of Washington State) were arrested. The landing at Kahoʻolawe inspired Hawaiians with the call to aloha ʻāina — to love and defend Hawaiian land and the Hawaiian nation. That dramatic moment signaled a new stage in the contemporary Indian and Hawaiian response to U.S. occupation, one that still connects today to Indigenous movements worldwide.

David A. Chang is a professor of history at the University of Minnesota and author The World and All the Things upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration, winner of the 2017 Albert J. Beveridge Award from the American Historical Association.

Read more about the raid here in the TIME Vault

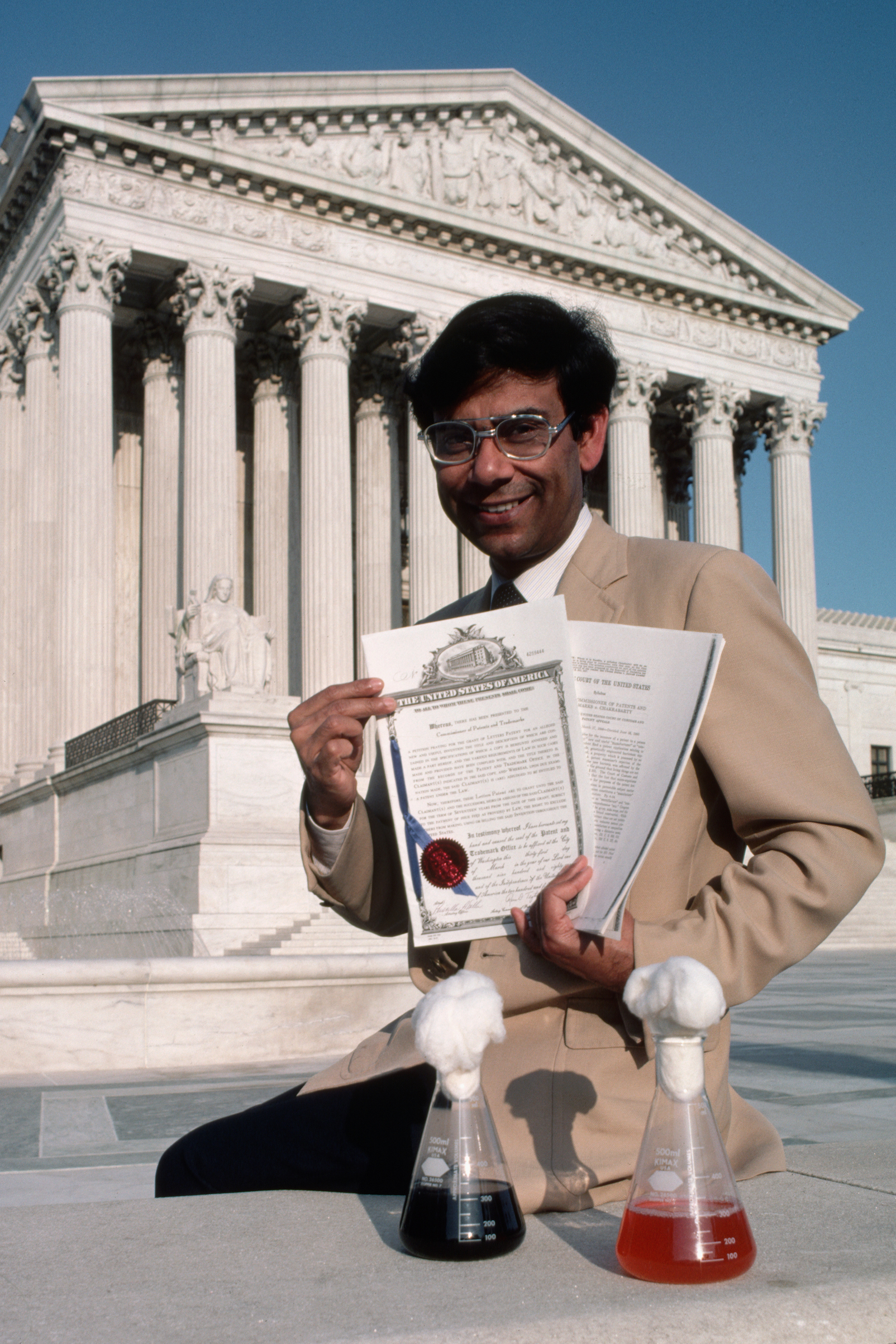

Genetically Modified Organisms Become Eligible for Patents (June 16, 1980)

The Supreme Court’s opinion in Diamond v. Chakrabarty concerned Ananda Chakrabarty, a scientist who sought a patent for a genetically modified bacterium that he had developed at General Electric. The bacterium had the capacity to digest crude petroleum products, so it was especially promising as a potential solution to oceanic oil spills. The Court ruled that the bacterium counts as a “manufacture” or “composition of matter” in American patent law, and that the fact that it is alive does not preclude its patent-eligibility. It also explained, citing the Congressional record, that patent law protects “anything under the sun that is made by man.” This ruling enabled inventors at private and public institutions alike to obtain patents for genetically modified organisms — from plants and animals for laboratory research, to many foods available in supermarkets today. It also encouraged biotechnology firms to rely very heavily on patent law, especially given the high research costs involved in developing new organisms that can reproduce on their own, and paved the way for the genetically modified world in which we live today.

Gerardo Con Diaz is an assistant professor of science and technology studies at the University of California, Davis, and recipient of the 2017 Bernard S. Finn IEEE History Prize from the Society for the History of Technology. His first book, a history of software patenting in the United States, will be published by Yale University Press in 2019.

Read more about GMOs here in the TIME Vault

Anita Hill Speaks Up on Harassment (Oct. 11, 1991)

We cannot forget what Anita Hill faced when she spoke up at the Senate judiciary hearings on the nomination of Justice Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Hill was one African-American lawyer facing an all-white, all-male Senate committee gathered to hear testimony on Thomas’ character, including Hill’s claims of sexual harassment as his employee at the U.S. Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Ultimately, Thomas was confirmed and Hill encountered public scrutiny as her credibility and veracity were questioned well after the hearing. Still, Hill’s brave testimony garnered a strong feminist mobilization and helped lead to the enactment of workplace and government policies on sexual harassment that would enable victims to seek justice.

In 2018, we bear witness to the reach and ramifications of the #MeToo movement, which began with another black woman,Tarana Burke, and has continued the difficult work of reshaping relations between men and women — and exposing the wrongdoings of powerful men, including those in Washington’s halls of power.

Marisa J. Fuentes is the Presidential Term Chair in African American History and an associate professor of women’s and gender studies at Rutgers University and the author of the Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive, winner of the 2016 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians Book Prize and the 2017 Association of Black Women Historians Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book Award.

Read more about Anita Hill here on TIME.com

A version of this list appears in the July 9 issue of TIME

Correction: July 18, 2018

The original version of this list misstated April Merleaux’s professional affiliation. She is now a professor at Hampshire College, not at Florida International University.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com