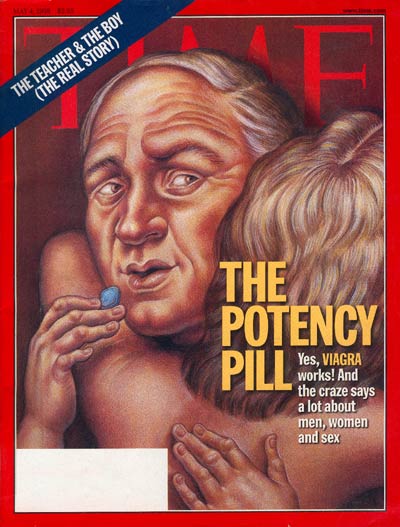

This Tuesday marks 20 years since Mar. 27, 1998, when the FDA approved Viagra as the first oral treatment for erectile dysfunction. Since the diamond-shaped blue pill hit the market, it has generated at least $17 billion in the U.S., Bloomberg reported in Dec. 2017.

In the drug’s earliest days, demand was so great that urologists bought rubber stamps so they could churn out prescriptions — as many as 10,000 scripts a day when it first launched, according to TIME’s May 1998 cover story on the drug’s social impact. Its instant success was a “lucky accident,” as the magazine put it, given that Pfizer scientists discovered the drug by accident in the ’80s, when, while researching a treatment for chest pain, they saw that the compound with which they were experimenting was increasing blood flow to the penis instead of the heart.

The drug was a breakthrough as a quick and painless way to treat erectile dysfunction (ED) — a condition that, until then, had limited treatments that ranged from unpleasant and strange (the surgical attachment of slivers of goat testicle to the patient’s body) to poisonous (strychnine, once marketed as “Nature Energizer Pep Tablets for Married Men & Women”).

TIME’s cover story featured some memorable reactions from patients who remarked on how revolutionary the drug was. A 55-year-old man in St. Petersburg, Fla. described it as “a little package of dynamite.” But, outside of the realm of the doctor’s office, those who closely watched the pill’s release often took a more theoretical interest.

On one end of the spectrum, sex therapist Dr. Ruth Westheimer was quoted by the magazine worrying that the pill wouldn’t help couples unless it were accompanied by “an education process” to add what she called sexual literacy to its physiological effects. (But if such literacy did increase, she noted, it could be great news for millions of American grandparents.)

On the other hand, some expected the pill to create a major change on its own. The editor of Penthouse magazine, Bob Guccione — who blamed feminism for having “emasculated the American male” and putting too much pressure on men — expected Viagra to “undercut the feminist agenda” by removing that pressure, and thus “free the American male libido.” Writer Gay Talese pointed to the rush on Viagra as evidence that sexual potency was key to “men’s self-worth,” no matter how much society tried to tamp it down.

Meanwhile, the social critic Camille Paglia said that she wanted men to “really re-examine why they need this pill” in light of the idea that if modern men couldn’t perform sexually “they’re going to evolve themselves right out of the human species.”

One thing that hasn’t changed between then and now is concern about who’s taking Viagra, why and what it does to them. One Stanford study that TIME reported on three years later suggested that the little blue pill might be much less magical than its initial reception implied: in the study, ED was more effectively treated with a combination of medication and therapy than by medication alone.

But the idea that a pill might solve such a problem remains tempting, Meika Loe, author of The Rise of Viagra: How The Little Blue Pill Changed Sex in America, told TIME in an email reflecting on the 20th anniversary. In her research, she said, she’s seen men who carrying the pill around with them in order to bolster their confidence, and a generation of people who hope to quickly do away with a problem that has complicated mental, physical and social connections.

“Viagra marks the start of the marketing of sexual dysfunction as a social and individual problem, and one to be solved by medicine. This commercial effort plays off the ubiquitous sexual insecurities we feel in society, and promotes a quick fix for the problem,” she said. “What this leaves us with is a pill with a physiological effect that may or may not solve anything because we are not treating the whole body, the whole relationship, or looking critically at social ideals about masculinity and sexuality.”

Today, though the word “Viagra” can still summon a range of ideas as varied as they were in 1998, prescriptions are down more than 20% since 2012, per the Washington Post. Price hikes made it less affordable than it had been, and the drug has faced competition from similar drugs such as Cialis and Levitra, and now Pfizer has rolled out a generic version in the United States. But, even if the name-brand drug is no longer the market force it once was, there’s no question that its impact on two decades of conversation about modern sex has been, as one user put it when discussing the drug’s effects in 1998, “absolutely incredible.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com