Less than a week after a shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., left 17 dead, survivors announced that they’re planning a “March for Our Lives” for March 24 in Washington, D.C., to pressure members of Congress to pass stronger gun-control legislation. Meanwhile, dozens of D.C.-area students have already staged a “die-in” outside of the White House — and more are in the works — and national school walkout days are planned for March and April. Their goal, as expressed in the name of their movement, is that such a thing should “Never Again” happen.

With the U.S. national voting age at 18, such actions are one of the few ways available for most high-school students to make their voices heard at the national political level. As Amy Campbell-Oates, a 16-year-old who organized a protest at South Broward High School near Parkland, told the New York Times, “Some of us can’t vote yet but we want to get to the people that can.”

And, while the platforms that young people are using to speak out may be new, there’s a long history of Americans who were too young to vote shifting the national conversation on social and political issues.

A Children’s Crusade

In fact, because the national voting age wasn’t lowered to 18 until 1971, it’s worth remembering that a fair amount of the most memorable civil rights and antiwar protests of the 1960s were staged by people who couldn’t vote yet. But children — children much younger than 18 — were also part of the history of activism before that point.

“The labor and socialist movements had youth affiliates going back to the beginning of the century,” says Maurice Isserman, professor of History at Hamilton College and co-author of America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s.

In one of the more dramatic examples, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones put children in animal cages to raise awareness of child-labor issues, and led the March of the Mill Children campaign that took place in July of 1903. During that episode, dozens of children were among the marchers who followed Jones from Philadelphia to New York to protest labor conditions, earning the event the moniker of the “children’s crusade.” (The name comes from a 13th century youth movement.)

Though that particular campaign didn’t lead to immediate change, the idea — that showing the world the children who were directly affected by policies about which they could not vote — was a powerful one.

‘A Little Child’ for Civil Rights

The Civil Rights Movement was a natural place for that idea to be reborn. Young people were both involuntary martyrs of the movement — most famously after the August 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till — and leaders seeking change in their own lives. One early example of a young person organizing an act of resistance on her own took place on April 23, 1951, when 16-year-old Barbara Johns led a walkout at the all-black Robert Russa Moton High School in Virginia to protest abysmal conditions. Johns contacted the NAACP, which took her case all the way to the Supreme Court, where it was one of the five cases involved in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education desegregation ruling. The Brown ruling, argues Rebecca de Schweinitz, a professor of History at Brigham Young University and author of If We Could Change the World: Young People and America’s Long Struggle for Racial Equality, put “school children at the center of the nation’s struggle for racial equality.”

In explaining why she had to act when she did, Johns quoted the Bible: “Our parents ask us to follow them,” a classmate later recalled her saying at the time, “but in some instances…a little child shall lead them.”

People too young to vote played a key role in the movement in the years to follow — for example, four college freshmen led 1960’s famous Woolworth’s lunch counter sit-in — and soon Martin Luther King Jr. and his fellow activists realized another unique role that children could play in their movement. That realization gave rise to an even more famous Children’s Crusade.

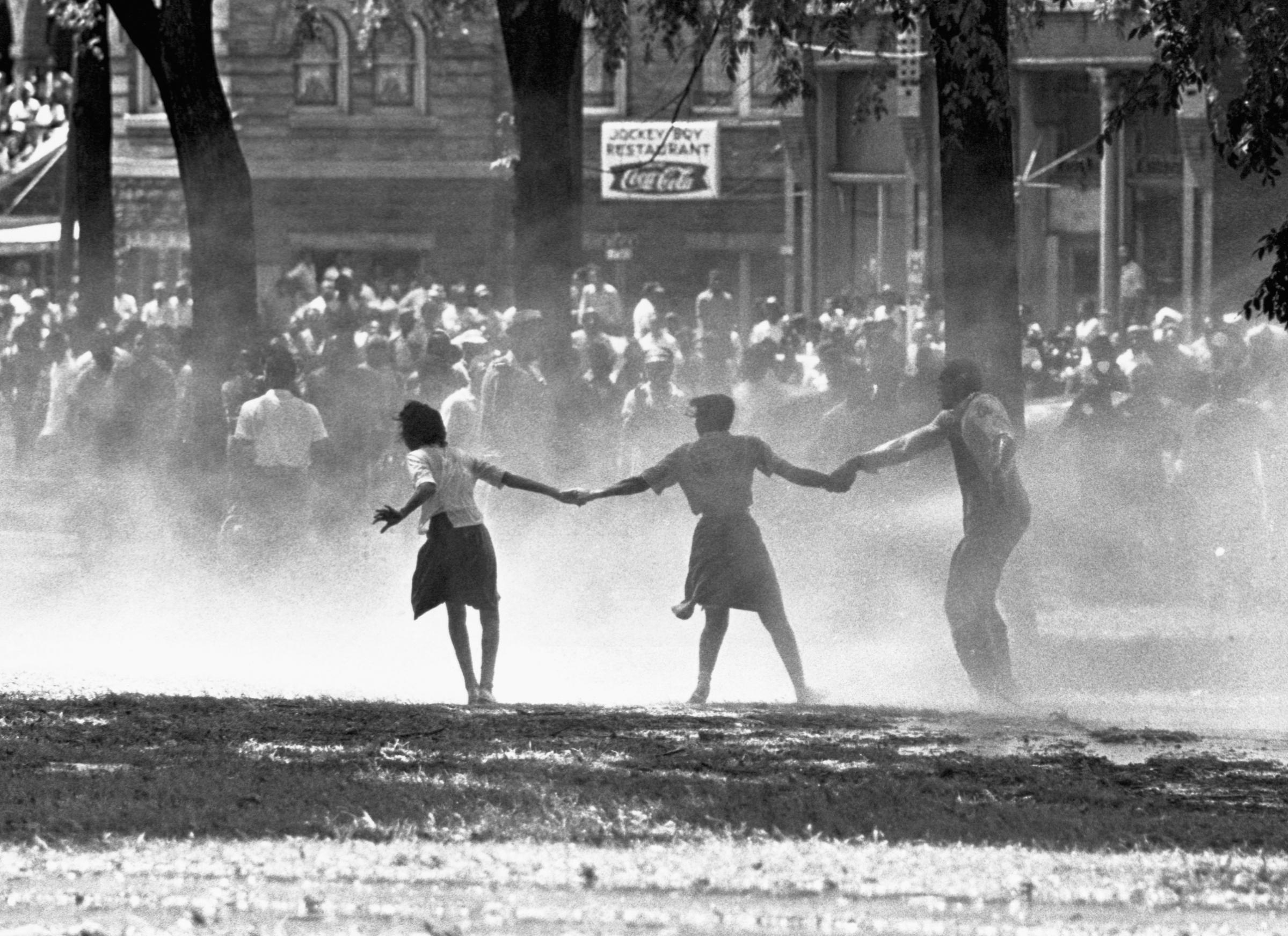

On May 2, 1963, more than 1,000 children in Birmingham, Ala., skipped class to demonstrate as part of the controversial protest. According to King’s colleague James Bevel, a key organizer of the campaign, part of the idea was that they knew the participants would likely be arrested, but a high-school student — unlike a worker — could spend time in jail without creating an economic problem for the community.

But the impact the students ended up having was more than just economic. Television footage of Birmingham police commissioner “Bull” Connor turning police dogs and firehoses on the children was a game-changer for politicians at the national level. That incident, followed by the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in September, which killed four young girls, helped pave the way for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. King scholar Clayborne Carson has described the Children’s Crusade as having “turned the tide of the movement.”

Despite the brutality they saw during the Children’s Crusade, young people remained at the center of the movement. For example, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee trained African-American children at “Freedom Schools,” which taught teens everything from black history to how to deal with hostile white peers.

Joined during 1964’s “Freedom Summer” by young men and women who attended colleges in the North, SNCC activists honed in on voting rights as their main goal, even though many of them were not yet old enough to vote themselves. They realized that “the surest way to achieve change was through electoral politics, getting African-Americans right to vote, so they could elect people to act in their political and economic interests,” says Kevin Gaines, a professor of Africana Studies at Cornell University and author of Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture During the Twentieth Century.

As today’s student gun-control activists of the Never Again movement also hope to demonstrate, they showed that being old enough to vote is not a prerequisite to helping to determine who gets elected.

Anti-War, Pro-Voting

Demonstrators at the University of California, Berkeley, started incorporating SNCC’s mass disobedience tactics for campus demonstrations in the fall of 1964. That December, hundreds of students occupied a campus building in what Isserman calls “the formative campus confrontation” over, among other matters, the rights of students to protest. Inspired by the student protests at Berkeley, student demonstrations spread at campuses nationwide, especially as the war in Vietnam escalated. And the protests weren’t just at colleges and universities.

A 13-year-old was at the center of one of the cases that significantly weakened that principle of in loco parentis, the idea that students surrender some rights when they go to school, as the school takes on the parental role. Junior high school student Mary Beth Tinker was suspended in 1965 for wearing an armband to school to protest the war in Vietnam. About four years later, in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

“Young people [were] claiming rights and winning them,” Isserman says, “and changing the legal structure of the country in the process.”

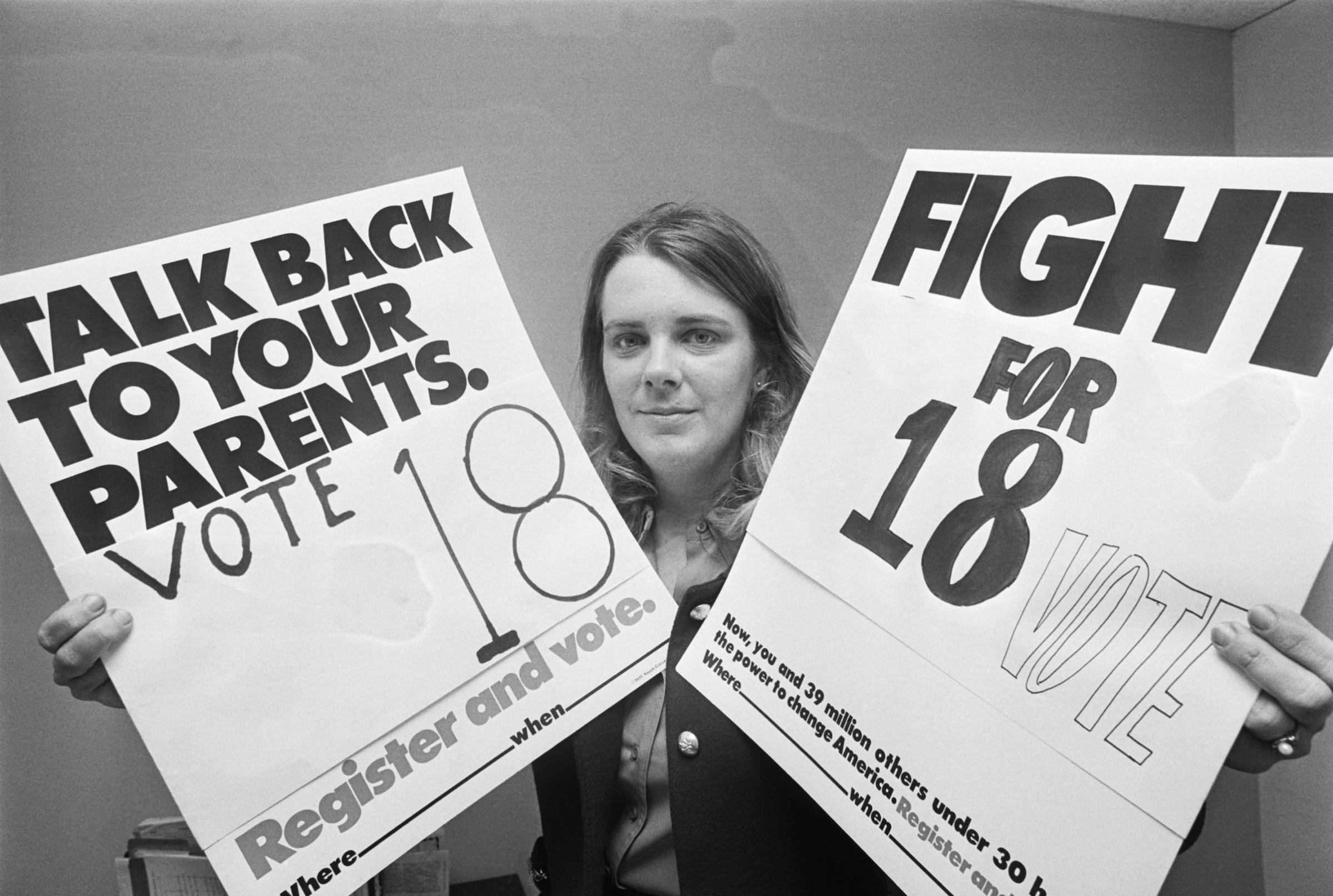

Politicians took note of this new level of political activism among students. Along with the War in Vietnam — which led to the refrain “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote” — recognition of that generation’s high level of formal schooling and civic education was a factor that led to the movement to lower the voting age to 18. As de Schweinitz writes in Age in America: The Colonial Era to the Present, “[it] was hardly accidental” that the issue sprouted in 1968, a watershed year when “militant youth protests” broke out over the Tet Offensive, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the release of the Kerner Commission Report, and particularly heated Democratic and Republican national conventions.

By 1970, de Schweinitz notes, Americans in the 18-to-21 age range were already participating in political activities, student-led demonstrations, voter registration drives, and political campaigns. “The young person can take the time to look at the system, question it, and attempt to change it,” as a 1968 White House report put it.

“At 18, 19, and 20, young people are in the forefront of the political process—working, listening, talking, participating…” Mike Mansfield, the Senate Majority Leader at the time, said during discussion of the matter in 1970. “I think those of us above the age of 30 could stand a little educating from these youngsters.”

The 26th Amendment, lowering the voting age to 18, was ratified in 1971.

What Comes Next

It’s too soon to tell what kind of impact the survivors of the school shooting in Parkland will have on the national gun-control debate, but American history suggests that there are two sides to the matter.

On the one hand, it can be hard to sustain a movement that is centered on a place from which its participants are supposed to graduate. “Student movements tend to be evanescent,” Isserman says. “When students graduate, they move on, and it’s left up to whoever comes along to continue [it]. They rarely leave a kind of institutional framework.”

On the other hand, today’s student protesters have tools at their disposal that their forebears lacked. While their predecessors in the civil rights movement had local radio DJs spread the word about protests using code words, and student activists today can address the public directly through social media. Plus, at least one idea that’s been floated in the wake of the Florida shooting does have historical precedent.

While there’s no major national movement to lower the voting age underway at the moment, one thing about young protesters is already certain. Though eventual graduation can be an obstacle for a student movement, aging out isn’t entirely a downside. After all, the young people who march next month for gun control, like the students who marched for civil rights or against war, eventually become the voters they once hoped to convince.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com