Editor’s note: On Jan. 12, Kate DiCamillo responded to de la Peña’s questions. Read her essay here.

Twice this past fall I was left speechless by a child.

The first time happened at an elementary school in Huntington, New York. I was standing on their auditorium stage, in front of a hundred or so students, and after talking to them about books and writing and the power of story, I fielded questions. The first five or six were the usual fare. Where do I get my ideas? How long does it take to write a book? Am I rich? (Hahahahaha!) But then a fifth-grade girl wearing bright green glasses stood and asked something different. “If you had the chance to meet an author you admire,” she said, “what would you ask?”

For whatever reason this girl’s question, on this morning, cut through any pretense that might ordinarily sneak into an author presentation. The day before, a man in Las Vegas had opened fire on concertgoers from his Mandalay Bay hotel room. Tensions between America and North Korea were reaching a boiling point. Puerto Ricans continued to suffer the nightmarish aftereffects of Hurricane Maria. I studied all the fresh-faced young people staring up at me, trying to square the light of childhood with the darkness in our current world.

All of this, of course, was wildly inappropriate for such a young audience — and had little to do with the question — so I just stood there in awkward silence, the seconds ticking by.

Eventually I gave the girl some pre-packaged sound bite about dealing with rejection, or the importance of revision, and then our time was up. But hours later, as I sat in a crowded airport, waiting for a delayed flight, I was still thinking about that girl’s question. What would I ask an author I admire? Writers like Kate DiCamillo came to mind. Sandra Cisneros. Christopher Paul Curtis.

Now I wanted a do-over.

A thoughtful question like that deserved a more thoughtful response.

Just as my plane reached its cruising altitude, it came to me. If I had the chance to ask Kate DiCamillo anything, it would be this: How honest can an author be with an auditorium full of elementary school kids? How honest should we be with our readers? Is the job of the writer for the very young to tell the truth or preserve innocence?

A few weeks ago, illustrator Loren Long and I learned that a major gatekeeper would not support our forthcoming picture book, Love, an exploration of love in a child’s life, unless we “softened” a certain illustration. In the scene, a despondent young boy hides beneath a piano with his dog, while his parents argue across the living room. There is an empty Old Fashioned glass resting on top of the piano. The feedback our publisher received was that the moment was a little too heavy for children. And it might make parents uncomfortable. This discouraging news led me to really examine, maybe for the first time in my career, the purpose of my picture book manuscripts. What was I trying to accomplish with these stories? What thoughts and feelings did I hope to evoke in children?

This particular project began innocently enough. Finding myself overwhelmed by the current divisiveness in our country, I set out to write a comforting poem about love. It was going to be something I could share with my own young daughter as well as every kid I met in every state I visited, red or blue. But when I read over one of the early drafts, something didn’t ring true. It was reassuring, uplifting even, but I had failed to acknowledge any notion of adversity.

So I started over.

A few weeks into the revision process, my wife and I received some bad news, and my daughter saw my wife openly cry for the first time. This rocked her little world and she began sobbing and clinging to my wife’s leg, begging to know what was happening. We settled her down and talked to her and eventually got her ready for bed. And as my wife read her a story about two turtles who stumble across a single hat, I studied my daughter’s tear-stained face. I couldn’t help thinking a fraction of her innocence had been lost that day. But maybe these minor episodes of loss are just as vital to the well-adjusted child’s development as moments of joy. Maybe instead of anxiously trying to protect our children from every little hurt and heartache, our job is to simply support them through such experiences. To talk to them. To hold them.

And maybe this idea also applied to the manuscript I was working on.

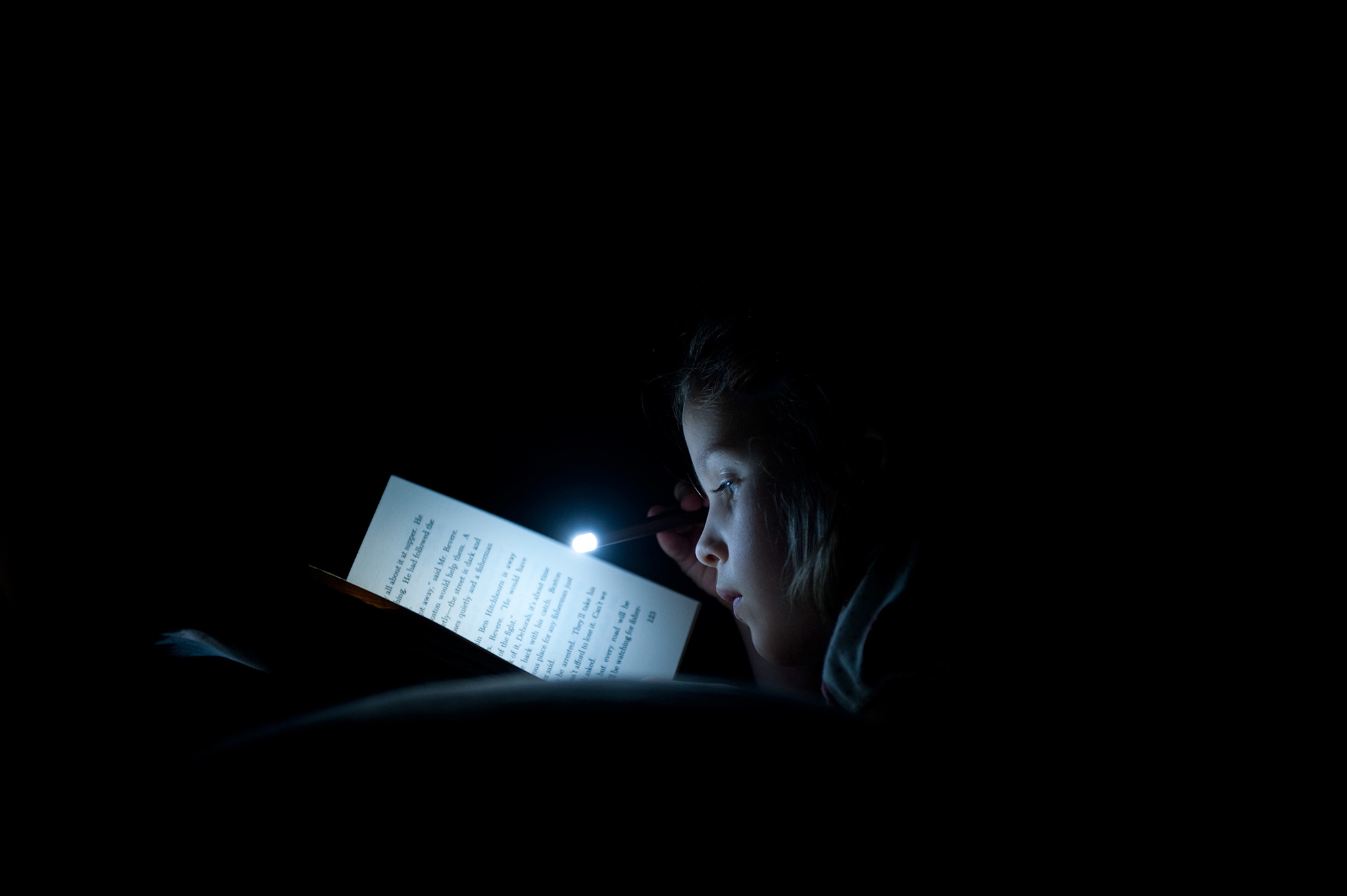

Loren and I ultimately fought to keep the “heavy” illustration. Aside from being an essential story beat, there’s also the issue of representation. In the book world, we often talk about the power of racial inclusion — and in this respect we’re beginning to see a real shift in the field — but many other facets of diversity remain in the shadows. For instance, an uncomfortable number of children out there right now are crouched beneath a metaphorical piano. There’s a power to seeing this largely unspoken part of our interior lives represented, too. And for those who’ve yet to experience that kind of sadness, I can’t think of a safer place to explore complex emotions for the first time than inside the pages of a book, while sitting in the lap of a loved one.

We are currently in a golden age of picture books, with a tremendous range to choose from. Some of the best are funny. Or silly. Or informative. Or socially aware. Or just plain reassuring. But I’d like to think there’s a place for the emotionally complex picture book, too. Jacqueline Woodson’s amazing Each Kindness comes to mind, in which the protagonist misses the opportunity to be kind to a classmate. Margaret Wise Brown’s The Dead Bird is a beautiful exploration of mourning from the point of view of children.

Which brings me to the second child who left me speechless last fall.

I was visiting an elementary school in Rome, Georgia, where I read and discussed one of my older books, Last Stop on Market Street, as I usually do. But at the end of the presentation I decided, on a whim, to read Love to them, too, even though it wasn’t out yet. I projected Loren’s illustrations as I recited the poem from memory, and after I finished, something remarkable happened. A boy immediately raised his hand, and I called on him, and he told me in front of the entire group, “When you just read that to us I got this feeling. In my heart. And I thought of my ancestors. Mostly my grandma, though … because she always gave us so much love. And she’s gone now.”

And then he started quietly crying.

And a handful of the teachers started crying, too.

I nearly lost it myself. Right there in front of 150 third graders. It took me several minutes to compose myself and thank him for his comment.

On the way back to my hotel, I was still thinking about that boy, and his raw emotional response. I felt so lucky to have been there to witness it. I thought of all the boys growing up in working-class neighborhoods around the country who are terrified to show any emotion. Because that’s how I grew up, too — terrified. Yet this young guy was brave enough to raise his hand, in front of everyone, and share how he felt after listening to me read a book. And when he began to cry a few of his classmates patted his little shoulders in a show of support. I don’t know if I’ve ever been so moved inside the walls of a school.

I hope one day I’ll have the chance to formally ask Kate DiCamillo my questions about innocence and truth. But I do know this: My experience in Rome, Georgia? That’s why I write books. Because the little story I’m working on alone in a room, day after day, might one day give some kid out there an opportunity to “feel.” And if I’m ever there to see it in person again, next time hopefully I’ll be brave enough to let myself cry, too.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com