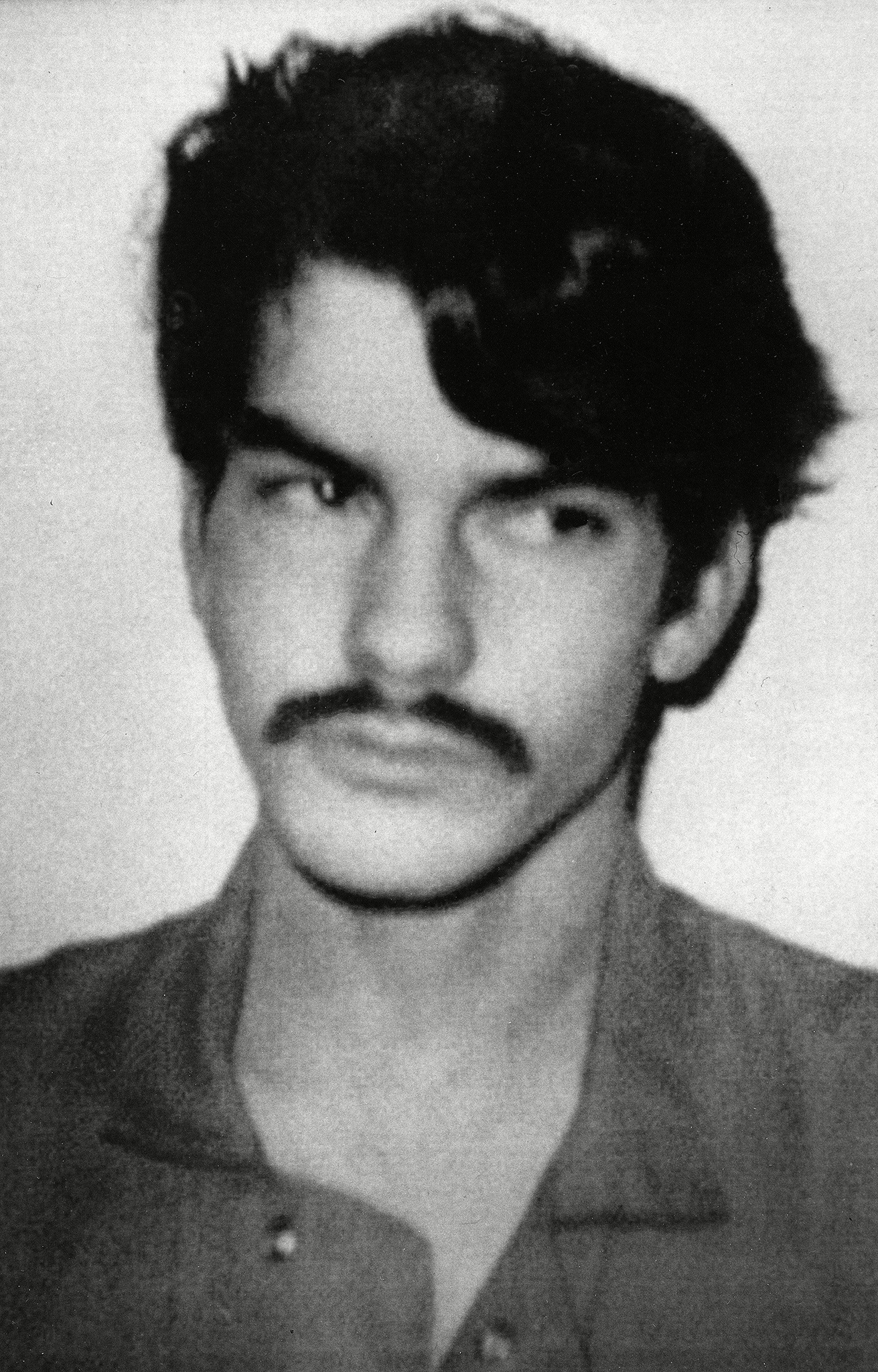

Friday marks 25 years since Washington State hanged admitted child molester Westley Allan Dodd for the kidnapping, rape and murder of three small boys. Though more than two decades have passed, the grisly case is still a lesson in the nature of crime and punishment in the United States.

Dodd, who had been molested himself as a child and had a long criminal history, said that he started the 1989 spree that led to his eventual arrest — stalking children, armed with shoelaces to tie up victims and a knife — because, in his words, he “didn’t have a TV” and was “getting bored.” In 1993, as the execution date approached, TIME described one of his most gruesome killings:

Dodd found a four-year-old boy playing alone in an elementary school playground. He coaxed Lee Iseli home with him to play some games. ”When we got there, I told him he had to be real quiet because my neighbor lady didn’t like kids,” Dodd said. He then stripped off Lee Iseli’s clothes, tied the boy to the bed and began taking Polaroid pictures as he molested the child. He later mounted the photos in a 4-in.-by-6-in. pink photo album labeled FAMILY MEMORIES.

He paused at one point to make an entry in his diary: ”6:30 p.m. Will probably wait until morning to kill him. That way his body will still be fairly fresh for experiments after work.” Dodd began strangling the boy at 5:30 a.m. He revived the child twice before finally killing him and hanging the body in a closet and burning the boy’s clothing, except the Ghostbusters underpants, which he kept as a trophy.

In addition to the brutal nature of the crimes, part of what got the case so much attention is that Dodd appeared to like the attention that came with his arrest. “He kept news clippings [of the crime], watched himself on TV, kept a diary,” says Dirk C. Gibson, author of Serial Murder and Media Circuses. Dodd also surprised many by speaking so candidly to the police. ”Each time I entered treatment, I continued to molest children,” he wrote in a 1991 court affidavit that was quoted by TIME. ”I liked molesting children and did what I had to do to avoid jail so I could continue molesting.” After his incarceration, he even wrote a “coloring book” for parents and children on how to avoid child molesters. “Most serial killers don’t go to such great lengths to produce a document like that,” Gibson adds.

Dodd specifically requested to be hanged because that’s how his last victim died. The Jan. 5, 1993, hanging was the first legal execution by that method since 1965, when Kansas executed George York and James Latham, who were famously associated with Richard Eugene Hickock and Perry Edward Smith, whose 1959 murder of a family inspired Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood.

Dodd’s request was unusual given that hanging “had fallen entirely into disuse by that point,” says Brandon Garrett, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. Public hangings outside courthouses would result in botched executions that created a “public discomfort with brutal execution,” so states moved to “control the process more in an effort to make it less public, more sanitary, more medical.”

For many observers, however, the idea of giving Dodd the death he requested did not sit right. National attention to Dodd’s execution, due to the gruesome nature of his crimes, drove conversations about how society addressed sex offenders — that his prior run-ins with the law had not gotten him off the streets left many feeling that such crimes were not taken seriously enough — and about the meaning of capital punishment.

“The prospect of what amounts to a glamorous public suicide was vastly more appealing than a life spent alone in a cell the size of a parking space, crushed by boredom, without the least chance of freedom,” TIME noted. “For him, perhaps justice would have been better served by denying him his death wish and letting him wait, for a very long time, for death to come to him.”

Since Dodd’s execution, two other hangings have taken place in the U.S., but other methods have execution have largely replaced it. Moreover, capital punishment has disappeared in many places throughout the United States.

And, 25 years later, something else remains notable about the case, too. In addition to being the first execution by hanging in nearly three decades, the Dodd case stands out as an extreme moment in a very particular time period marked by heightened awareness of sexual violence.

As Philip Jenkins, author of Moral Panic: Changing Concepts of the Child Molester in Modern America and professor of History at Baylor University, explains, many of the terms associated with the topic — from “sexual predator” to “stalking” — either originated or were popularized during the early 1990s. Pop culture, with movies such as Thelma and Louise, also fueled the conversation. News about ritual child abuse and charges of abuse within the Roman Catholic church also fueled “talk of an abuse ‘epidemic,'” Jenkins told TIME in an email. On the other side, he adds, the press eagerly reported on vigilantism directed at child molesters.

“Those very few years witnessed a kind of revolution in gender conflict,” Jenkins puts it, “which found demon figures in people like Dodd.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com