As I waited in line for a bathroom outside the Vermeil Room of the White House, Jacqueline Kennedy, painted in a floor-length peach gown, looked down at me from the wall, and I wondered if the other trans, queer and bi women in line with me felt as out of place as I did. We were from across the country and were considered the next generation of LGBTQ leaders, all under the age of thirty, by the Obama White House. Together with Michelle, we toured the East Wing, we listened to policy roundtables, and we ate barbecue with Vice President Joe Biden and Dr. Jill Biden.

Growing up in Hawaii, I’d never imagined that my writing as a trans woman of color would open doors for me in Washington. That I was waiting to use a ladies’ powder room in the residence of America’s black first family, who had invited me here, felt like make-believe. Just two weeks before, I’d been curled up next to my boyfriend on a well-worn love-seat in our 400-square-foot Manhattan apartment, watching Michelle Obama speak at the 2012 Democratic National Convention. She’d hypnotized me in HD, as I watched her vouch for her husband — like me, an African-American who called Hawaii home. She smiled, she quipped, she was sincere. Casting off the constraints of First Lady-hood in the brightest of colors, she wore a sleeveless A-line dress made of shimmering silk jacquard and designed by Tracy Reese, a similarly hued African-American woman.

I noticed how much more comfortable Michelle was on that stage than she had been in 2008 — speaking to the audience, to me, as if I were her most trusted friend. Now we knew her — as well as we could know one of the most visible black women in the world — and she seemed willing to hand over her most private, genuine self.

She told us how “worried” she was when we all first met in 2008. How fearful she had been about life at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, built by slaves, and its potential to isolate her from the people she and her husband had vowed to serve. But instead of being overwhelmed by her new life, she leaned into it and made the role of America’s First Lady all her own.

Michelle spoke it plain. Her gift was her ability to address the truth of the matter, and I always believed her — probably because she was not a politician, because she was doing unpaid labor, because she was investing her talents in a country that had often made her feel as if she would never measure up, never truly belong simply because she was a black woman. Her long, dark, strong arms seemed broad enough to hold all of her selves: the descendant of slaves, the girl raised on Chicago’s historically black South Side, the daughter of a Chicago city pump operator with multiple sclerosis, the Princeton- and Harvard-educated lawyer, the hospital executive, the self-proclaimed Mom-in-Chief who knew she needed her own mother to help raise her daughters under the glare of the spotlight.

On that DNC stage in 2012, Michelle reintroduced us to the man with whom she fell in love. Her bright smile perfectly punctuated her frequently Tweeted line, “We were so young, so in love, and so in debt.” She highlighted Barack’s guiding principles and in turn gave us all a moral roadmap to follow. She discussed the “values and visions” to which we, as citizens, should all aspire. She talked about showing gratitude for everyone, “from the teachers who inspired us to the janitors who kept our school clean.”

One particular moment from that speech has become my own guiding principle: “When you’ve worked hard, and done well, and walked through that doorway of opportunity, you do not slam it shut behind you. You reach back, and you give other folks the same chances that helped you succeed.” This sentiment had brought me to the White House just weeks after her speech. With Michelle’s invitation, she seemed to be saying that this house belonged to me; it belonged to us — each and every one of us in that line who had, like Michelle, been told we did not belong.

I left the White House that day feeling uplifted and affirmed. It seemed to me that it was my generation’s duty to, in her words, help “build a country worthy of [our] boundless promise.” In their eight years in the White House, the Obamas pushed its doors wide open. They welcomed both the American people and a diverse administration that reflected the entirety of our country. They ensured that we all knew that the White House was not merely a monument — it was the People’s House. She made it clear that when she, as a black woman, entered that historic space, she may have been the first to be let in, but that it was her duty to ensure that she would not be the last.

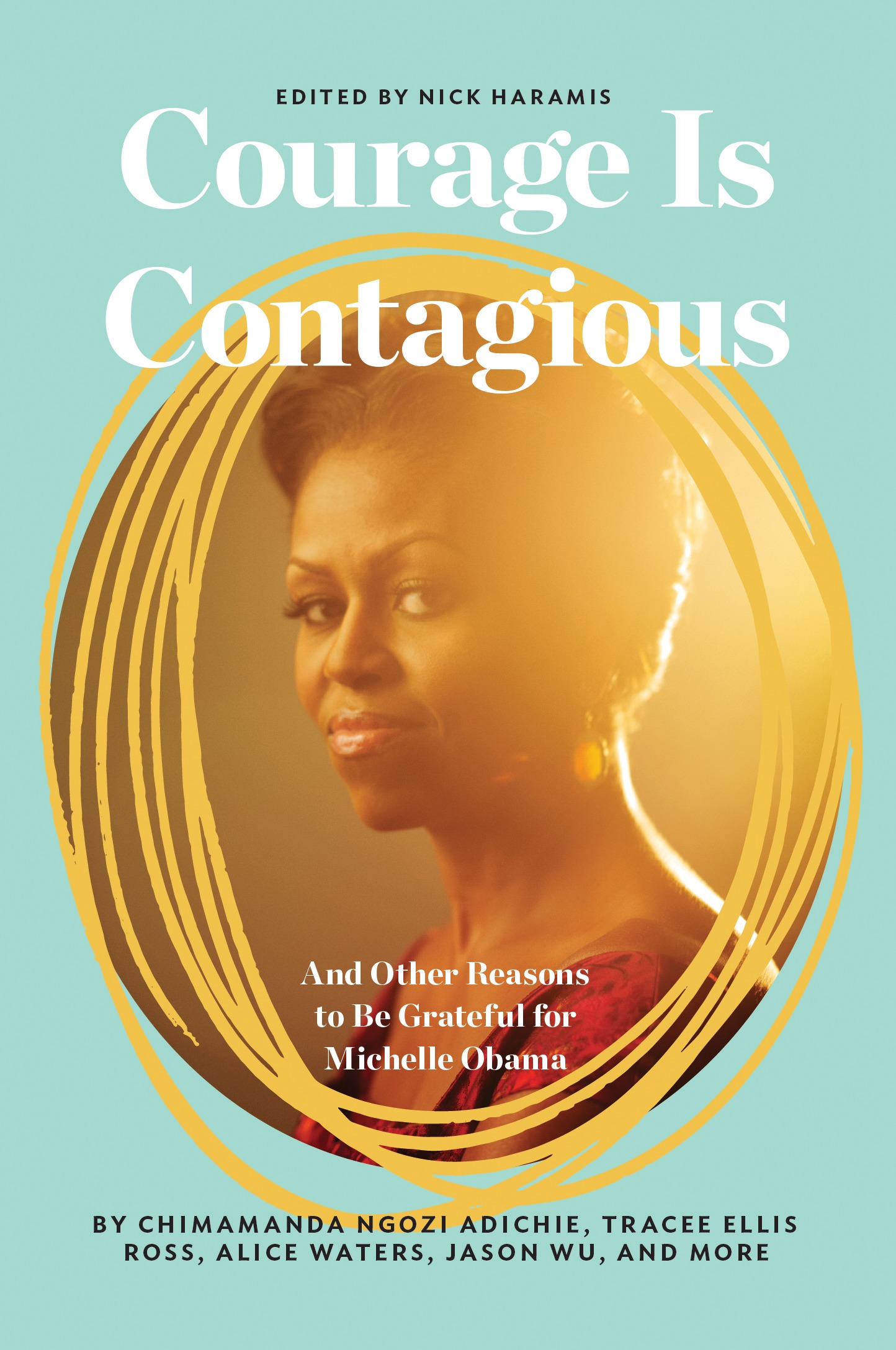

Janet Mock is the author of Redefining Realness and Surpassing Certainty. Excerpt from an essay by Janet Mock from Courage Is Contagious edited by Nick Haramis, copyright © 2017 by Janet Mock. Used by permission of Lenny, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com