Bonnie Wirtz was tending to her Minnesota farm one summer evening in 2012 when a crop duster buzzed low overhead. The aircraft sprayed chemicals on her property, missing its target next door. Soon the fumes seeped into her home through the air conditioner, and Wirtz wound up in an emergency room, coughing and bewildered and worried about the health of her 8-month-old son.

She had been sickened by a reaction to a pesticide called chlorpyrifos, which the agriculture industry uses to kill insects and worms on everything from cotton to oranges. A growing body of scientific evidence has linked the pesticide to health problems in children. Indeed, Wirtz’s son was diagnosed in 2015 with a developmental disorder that affects the functioning of the brain. It was the kind of episode that pushed the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that same year to propose banning the chemical altogether for most uses.

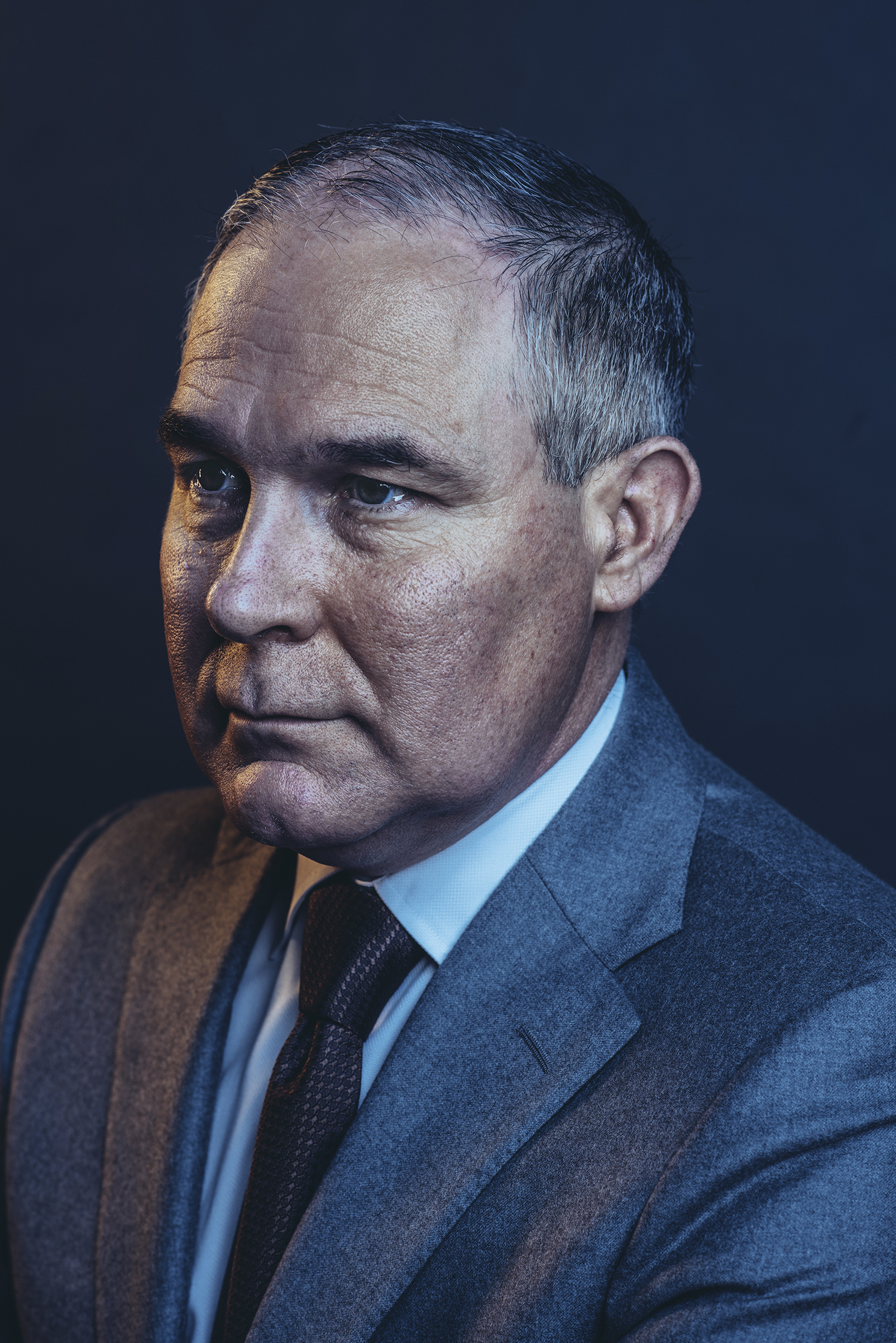

But when Scott Pruitt took over in February, the agency reconsidered. Pruitt, a former Oklahoma attorney general, came to the EPA on a mission to change it from within. Since its founding in 1970 under Republican President Richard Nixon, the agency’s primary task has been to keep people safe from toxic pollutants. Pruitt has pioneered a radically different approach to environmental regulation, weighing impact on job growth and the concerns of business groups on a level plane with environmental protection when the law allows. In March, less than a month after speaking with the CEO of Dow Chemical, the primary maker of chlorpyrifos, Pruitt reversed course, delaying a decision on the pesticide until 2022. (An EPA spokesperson said the conversation was brief and chlorpyrifos was not discussed.)

In an interview with TIME on Oct. 18, Pruitt dismissed criticism of his industry-friendly approach. “I don’t spend any time with polluters. I prosecute polluters,” he says. “What I’m spending time with is stakeholders who care about outcomes. I think it’s the wrong premise. It’s Washington, D.C.–think to look at folks across the country–from states to citizens to farmers and ranchers, industry in general–and say they are evil or wrong.”

But the sharp turn at the EPA and Pruitt’s close ties to the industry have raised questions about whose interests the agency is protecting. Since he took office, more than a dozen EPA regulations have been killed or put under review, from fuel-efficiency standards to regulations on the disposal of coal ash to restrictions on toxic metals like arsenic in waterways. Moreover, the Trump Administration has proposed slashing funding for the agency’s law-enforcement branch, which identifies polluters under existing regulations.

All this has aided businesses, propping up the declining coal industry, ensuring profit margins for chemical makers and reducing compliance costs for farmers. But the change has also weakened an agency designed to save lives. “They’re trying to deconstruct and dismantle the basic protections,” says Mustafa Ali, a career EPA official who resigned in March after 24 years. “They’re creating situations where more folks are going to get sick, some folks are going to die, more folks are going to be put in harm’s way.”

Pruitt’s work at the EPA is part of the Trump Administration’s larger project of rolling back decades of regulations across government. From the Departments of Education to Energy to Housing and Urban Development, Trump has appointed Cabinet Secretaries who are openly skeptical about the missions of the departments they now control.

Pruitt’s quest to remake the agency has gotten pushback from all sides: environmental groups that sue over every move, career staff reluctant to gut the EPA and even hard-line conservatives who think he moves too slowly. The outcome of these fights will be pivotal, not just for the Trump Administration and its supporters in industry but also for the well-being of millions of Americans.

Pruitt has made his immense wood-paneled office in Washington’s Federal Triangle his own. Framed baseball jerseys decorate one wall. Ronald Reagan memorabilia is displayed in a cabinet alongside a Fox News mug, and a bison bust rests on his desk in homage to his home state of Oklahoma. In conversation, he slips between chitchat and complicated policy, wrapping statements questioning the legitimacy of climate change in lawyerly language.

Yet Pruitt does not seem entirely at home at the EPA. His suite on the third floor of its neoclassical headquarters is often off-limits to most career staff. He travels with a 24-hour security detail, an unusual and costly move. During the early months of his tenure, he often chose a staffer’s office to make calls, presumably to stave off leaks. More recently, he installed a $24,570 soundproof booth to ensure that his phone calls are secure.

Pruitt rankled many of the agency’s career employees from the start. In a February speech, he painted the EPA as a federal bureaucracy run amok. He would change that, he declared shortly thereafter, by “getting back to basics” at the agency. “Our job is to enforce the law,” Pruitt tells TIME. “What has happened the last several years is that this agency–among others, but this agency particularly–has taken those statutes and stretched them so far.”

At the center of this realignment is a change in how the EPA assesses the costs and benefits of regulations. In Pruitt’s view, protecting the environment is just one element of his job as the country’s chief environmental regulator, on par with promoting the economy. The move to protect business comes as little surprise to those who have followed Pruitt’s rise. Pruitt made his reputation in Republican circles as one of the EPA’s toughest critics; as Oklahoma attorney general, he sued the agency 14 times. A 2014 New York Times report documented how on several occasions Pruitt sent complaints to the EPA at the request of energy companies, copying their proposed language nearly word for word on his official letterhead. Since moving to Washington, Pruitt has selected former industry officials as chief advisers. Schedules released in response to open record requests show that his calendar has been crammed with meetings with industry executives, from the president of Shell Oil Co. to Bob Murray, the Ohio coal baron. The rare meetings he has taken with environmental groups have not accomplished much. “None of us are under any illusion about who he is and what he represents,” David Yarnold, who heads the National Audubon Society, told TIME after meeting with Pruitt in April.

Pruitt’s approach to dismantling environmental regulations often follows a pattern. First, the administrator meets with an industry group. Then the group petitions for a regulatory change. Soon after, Pruitt announces a review along the lines the group requested. In most cases, Pruitt does not argue that regulations have no benefits. Instead, he attacks them as inconsistent with the letter of the law and argues that the economic costs outweigh the benefits.

Take the Clean Power Plan, which was devised by the Obama Administration as a way to fight climate change. Many conservatives abhor the rule because it intervenes in state energy policy and hurts the GOP-friendly coal industry. When it was announced in 2015, the EPA estimated the measure would slash the amount of sulfur dioxide emitted by power plants by 90% and cut nitrogen oxides by more than 70%. Both pollutants contribute to smog as well as a substance known as particulate matter, which triggers heart attacks, aggravates asthma and affects lung function. According to the EPA’s 2015 analysis, the plan would have saved 3,600 lives by 2030 and offered health and climate benefits of at least $34 billion a year.

But Pruitt rejects the idea that the agency should consider such health data and tells TIME that addressing such pollution should be left to other regulations. As he reviewed the Clean Power Plan over the past seven months, Pruitt has focused instead on the billions of dollars that the regulation costs the coal and power industries, accusing the Obama Administration of federal overreach. The rule was stayed by the Supreme Court, bolstering Pruitt’s overreach argument. “We shouldn’t put up fences. We shouldn’t say we have this tremendous natural resource, don’t touch it,” Pruitt tells TIME. The EPA, he says, should be about “managing that natural resource–whether it’s water or fossil fuels or land.” In October, Pruitt began the process of canceling the plan.

He’s right that the regulation would have hastened the decline of the coal industry, though energy analysts say his move won’t save it. And coal carries costs of its own. “It’s extremely shortsighted,” Christine Todd Whitman, a former Republican governor who ran the agency for two years under President George W. Bush, says of Pruitt’s opposition to the plan. “To clean up the air, to help reduce that from an economic point of view makes a huge amount of sense.”

Pruitt has taken a similar approach to chlorpyrifos. The EPA banned the chemical from most residential usage in 2000, citing a suspected link to brain defects in children. Since then, scientific data has shown that farmworkers and children in agricultural communities are particularly at risk. One study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, indicated that children born in close proximity to a farm where the chemical has been used have lower IQs than their counterparts born elsewhere. Another study of pregnant women by Columbia University researchers found that exposure to the chemical changes the brain structure of their children. But farmers around the world rely on chlorpyrifos. And while Dow Chemical does not say how much it makes from the product, the company has said in court that it would be “significantly impacted” by a ban. In addition to those costs, Pruitt has argued that the science is not conclusive. A federal court ruled in the EPA’s favor on the matter in July.

Pruitt’s moves alarm not only environmentalists and public health advocates but also many moderate Republicans. “There is no precedent for the range of apparently skeptical reviews of EPA regulations,” says William Reilly, who ran the agency under President George H.W. Bush. “I’m not confident that the integrity to the entire legal apparatus is really safe.” Some industry officials who worry about economic stability almost as much as overregulation say Pruitt may tip the balance too far in one direction, setting up the agency for another dramatic shift when a new President comes to town. “Virtually everyone in the business community believes that EPA needs to issue a replacement rule” to address climate change, says Jeff Holmstead, a senior EPA official under George W. Bush who now represents energy companies. “They think they would be better off with a reasonable regulation than with no regulation at all.”

Meanwhile, critics on the right complain that Pruitt has not gone far enough. Myron Ebell, who led Trump’s EPA transition team, says he wants Pruitt to challenge the EPA’s endangerment finding–the scientific document underpinning the agency’s global-warming regulation. “It’s essential,” Ebell says. But Pruitt is savvy about which battles he picks. Challenging the endangerment finding would trigger a legal fight much like that which ensnared Trump’s ill-fated travel ban. Instead, Pruitt has devised a strategy to publicly debate–and likely undermine–climate science while working bureaucratic channels to weaken regulation behind the scenes.

All this has earned Pruitt Trump’s ear as well as his praise. Trump has cited the work of the EPA, and the decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement–a move that bears Pruitt’s fingerprints–on a short list of his top accomplishments. “One of the biggest areas of success for the Trump Administration has been turning around really big regulations,” says West Virginia attorney general Patrick Morrisey, who worked with Pruitt on the Republican Attorneys General Association. “Pruitt is the driving force behind that.”

In some ways that’s because he is the President’s stylistic opposite. While Trump speaks in generalities and governs by tweet, Pruitt can talk the nuts and bolts of policy and works the levers of his agency slowly and subtly. If the President is impulsive, Pruitt thinks two steps ahead. It is a measure of his political acumen that he has thrived despite often being at odds on climate policy with some of the President’s closest confidants, such as his daughter Ivanka Trump and son-in-law Jared Kushner.

It is one reason why many observers believe Pruitt has his eye on a political job, such as governor of Oklahoma or one of the state’s U.S. Senate seats. For all his impact at the EPA, Pruitt seems destined to spend much of his time at the agency battling environmentalists and blue-state attorneys general, who are filing lawsuits to challenge every regulatory rollback. This summer, a federal court rejected an attempt to delay a rule curbing methane emissions, and Pruitt backed off a similar delay to a rule on ozone.

But even if Pruitt were to depart today, his tenure would still leave a substantial mark. The chemicals and pollutants spilling into our air and water will not just disappear when a new EPA chief comes to town. And neither will the health effects. Just ask Bonnie Wirtz. “This shouldn’t be happening,” she says of the EPA delay on chlorpyrifos. “We have the scientific evidence for a ban. Let’s do it.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com