Nowhere are a president’s persuasive abilities more necessary, and the people more receptive to them, than in the aftermath of a tragedy. But why do we expect a partisan political figure to soothe our nation’s jangled nerves after a disaster? The answers lie in the nature of the office, the men who have held it, modern public grieving rituals and contemporary media culture — but also in the cumulative impact of crises and the expanding demands on presidents as power has accrued to them.

The president becomes the father figure:

Ever since George Washington earned the designation “Father of Our Country,” from his earliest days as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, we have seen our nation’s chief executives as paternal, even priestly, symbols. Secular and religious fathers are expected to comfort their families and flocks during crises.

The president becomes the unifier:

Lincoln, known as “Father Abraham,” not only saved the Union but also tried to “bind up the nation’s wounds” as he looked toward the Civil War’s end, aiming to reunite Americans split asunder by the Confederacy’s 1861 secession. Named for Abraham, the Biblical prophet, Lincoln also established the gold standard for presidential eulogies at Gettysburg in 1863. He elegantly embraced the office’s dual roles as both the head of government and the head of state. Unlike a prime minister, who leads the government while a monarch or president performs ceremonial duties, an American president embodies the obligations of ruler and sovereign. From pardoning the Thanksgiving turkey each year—an idea that was formalized under President George H.W. Bush in 1989—to leading somber national mourning services, the president presides over the rituals that constitute American national tradition.

The president becomes the voice of the nation:

As the only nationally elected official, a president speaks for the country at home and abroad. In 1936, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this role in foreign affairs, via its opinion in U.S. v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., noting that the Founding Fathers vested the president (FDR in this case) with foreign policy power so that he might provide unified statements for the nation.

The president becomes the subject of grief:

Because we view them as the head of our national family, we mark their passing, especially if sudden and violent, with an outpouring of emotion. The deaths of incumbents Lincoln, Garfield, McKinley, FDR and JFK prompted public sorrow and private upset. Researchers discovered after John F. Kennedy’s 1963 assassination that many Americans suffered the same symptoms evident when a close family member dies: uncontrolled crying, sleeplessness, loss of appetite. When our anchor in times of tragedy becomes the victim of it, we feel adrift and look to the new president to reestablish our moorings. President Lyndon Johnson’s brief remarks on the Andrews Air Force Base tarmac, just after the nation watched JFK’s casket removed from Air Force One, followed by Mrs. Kennedy in her blood-stained suit, provided a necessary balm for the shocked nation.

Emotion becomes acceptable:

In modern times, the stiff upper lip has become anachronistic. After public tragedies, memorials of flowers, balloons, teddy bears and signs proliferate. Perhaps the best example of this lesson comes from across the pond: woe to the head of state who fails to join in public grieving rituals, as Queen Elizabeth II discovered after Princess Diana’s untimely death in 1997. In contrast, President Bill Clinton’s genuine union with the survivors of the 1995 federal building bombing in Oklahoma City actually resurrected his presidency

Modern communications and travel accelerate the timeline:

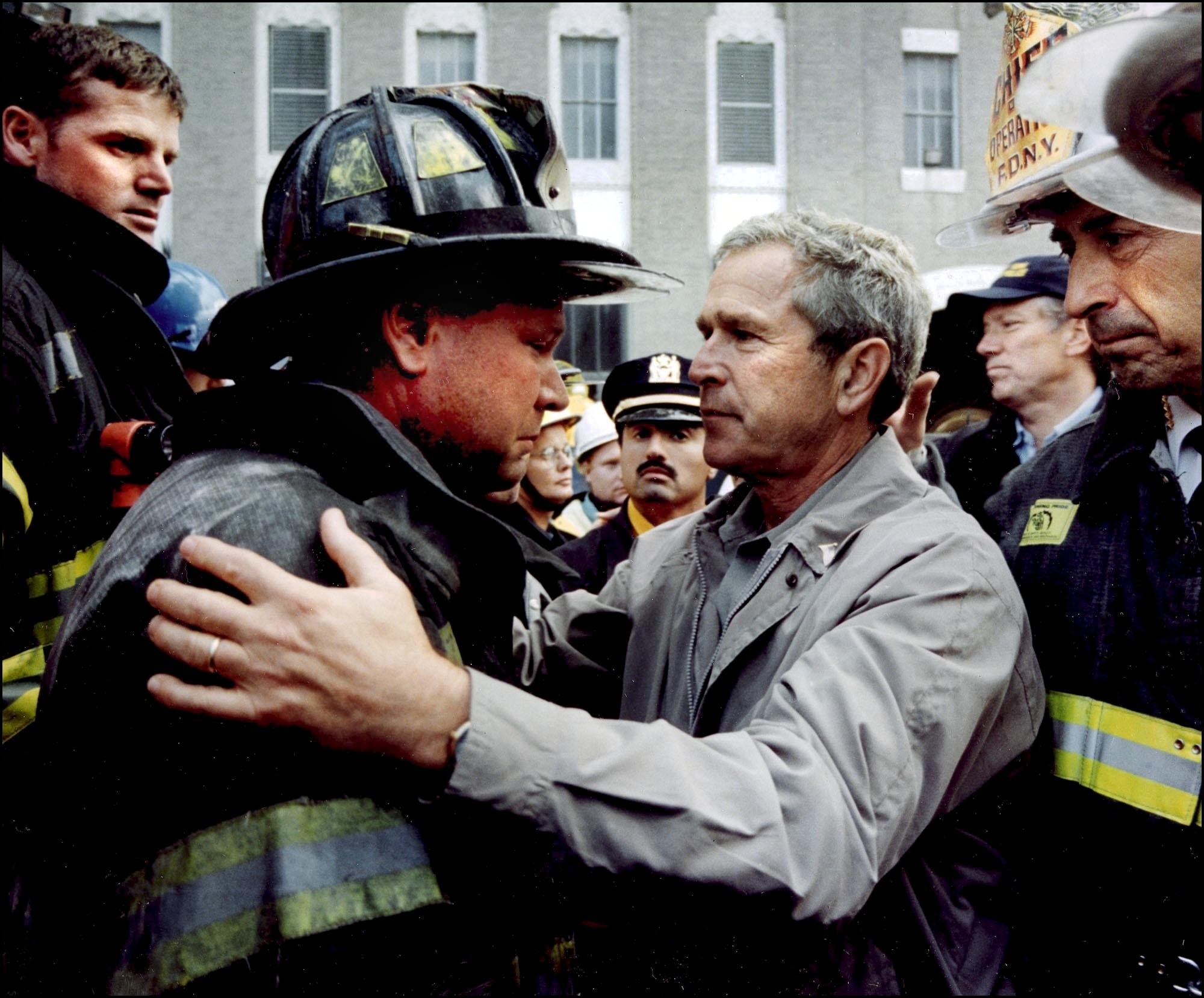

When the Titanic sank in 1912, President William Howard Taft received very few details initially, including that his military aide and dear friend Major Archibald Butt had perished aboard the doomed ship. Taft issued a heartfelt statement about his beloved staffer but wasn’t expected to meet with survivors. Presidents now learn about tragic events instantaneously and can travel to the scene effortlessly—and American knowledge of tragedies is widespread. Victims’ faces confront us at every turn, and families tell intimate stories of their loved ones taken all too soon. President George W. Bush’s unforgettable appearance atop a collapsed fire engine at New York City’s smoldering World Trade Center ruins in 2001 inspired first responders, victims’ families and a stunned nation, especially when he ad-libbed through a bullhorn: “I can hear you, the rest of the world can hear you, and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!”

24/7 coverage and social media proliferate:

The same technology that delivers these tragedies directly to our homes and smart phones has become the conduit for instantaneous presidential condolence messages. Within a few hours of the Las Vegas massacre, President Donald Trump tweeted, “My warmest condolences and sympathies to the victims and families of the terrible Las Vegas shooting. God bless you!” Visits to cities and towns devastated by natural and man-made disasters soon follow. When Mother Nature wreaks havoc, victims expect presidents to arrive with tangible federal assistance. It’s politically wise for chief executives to make the optics of these visits work, and missing the mark on those moments can have broad repercussions: photos of George W. Bush flying over the Katrina-ravaged Gulf Coast in 2005 haunted his presidency.

As media bombard Americans with the facts of human tragedies, those at the site and throughout the nation demand that the president help ease their pain. A secular liturgy has formed around the modern presidential response: a formal condolence statement from the White House, followed by a sacramental ritual of visiting survivors and victims’ loved ones and participating in public memorials. Clinton in Oklahoma City and Obama in Tucson/Newtown/Charleston/Orlando epitomized modern presidential outreach to salve the nation’s wounds. If the president speaks poetically and delivers his lines to perfection, as with Reagan’s memorable 1986 farewell to the space shuttle Challenger’s victims, his words will resonate and comfort forever: “They slipped the surly bonds of earth” and “touched the face of God.”

Barbara A. Perry is Presidential Studies Director at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, a non-partisan think tank focused on the presidency. Follow her on Twitter @BarbaraPerryUVA.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com