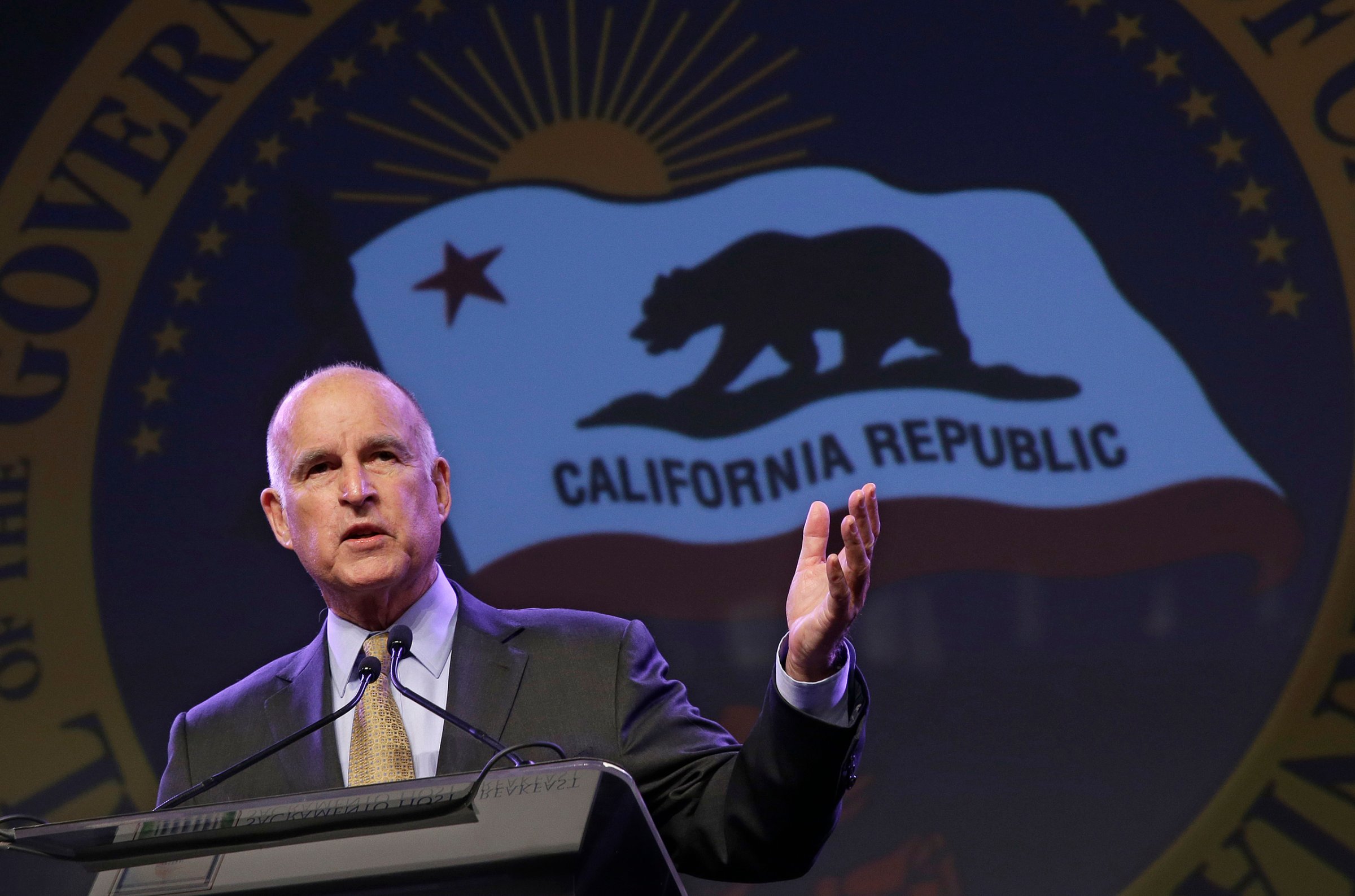

With Republicans dominant in Washington, the most powerful Democrat in America might be a man who lives about 2,700 miles from the capital: California Gov. Jerry Brown.

As Brown nears the end of an unprecedented fourth term as governor, many are looking to California to push back against a Republican agenda. And it is. Cities, counties and the state itself have filed lawsuits over everything from sanctuary city funding to energy-efficiency standards. After President Donald Trump decided to leave the Paris climate agreement, Brown happily jumped into the task of serving as America’s global climate change crusader — a position that would not have been so available had Hillary Clinton won the election.

Brown has a to-do list a mile long and limited time to take advantage of his “Trump bump.” As he nears the twilight of a career that spans nearly half a century, TIME spoke to Brown in his Sacramento office about his passion on climate change, Trump’s election and why Brown doesn’t want people asking about his legacy. The following excerpts have been edited for brevity and clarity.

You called Trump’s decision to leave the Paris agreement “misguided” and “insane.” Why those words?

“Misguided” because obviously if he was more wisely guided he would have never done it. “Insane” because the effort he has embarked upon with coal and fossil fuel will increase the build up of heat-trapping gases and not only raise the climate, it will create more storms, more sea level rise, more spread of lethal diseases, more turbulence in the world, and undermine the very stable conditions that for millennia have sustained life. So I’d would say anybody that wants to destroy at that level is engaging in very insane behavior.

There are a lot of people looking to California as a seat of Democratic resistance. Should they be?

I am glad you used the term resistance because I don’t use that term. I’d like to reframe it as action. And we started taking action in California long before Donald Trump was even heard of. So there are things he is doing and saying that I don’t agree with or don’t like, but we are on our own positive program on reducing air pollution, on building high-speed rail, on extending healthcare to millions of people, to treating our immigrants fairly. And we will continue down that path. And to the extent that the Trump Administration tries to throw up roadblocks, we will try to combat that and take action against it where we can.

What does the election of Donald Trump teach us about America?

Well, it teaches us that a lot of people did not like Hillary Clinton, that the Republicans over many years did a very effective job at undermining her credibility and … of course there are various policy issues. But it tells you there is a deep disorder in contemporary politics. One example is the election of Donald Trump and his comments that have no basis. For example, that climate change is a hoax cooked up by China.

Also the latest fiasco on the Affordable Care Act. The Republicans for six years made that a central plank in their platform. Then, when they are given the chance, many of them began to say “Wait a minute. Do we really want to take health insurance away from 20 million Americans?” … For years a major political party can engage in debates that if they thought more deeply about it, they would have very little to do with. So that would say that there is a superficial, unreal quality about a lot of the debate and discussion going on in the public life of America.

You said when you were younger, watching your dad be a politician, that you were attracted and repelled by politics. How do you feel about that now?

Well, I enjoy it more now, that is true. I was a little shocked [back then] but the fact of the matter is this political world is a combat. It’s quite a collision of very different ideas and that is part of how we resolve disputes. It’s messy, in many ways it’s dismaying, but it is the democratic process. And so what I said is what I felt and do feel, but I also see that it is our way and it has done some very good things, our democratic governance. But it has great peril if we, the leaders, don’t take things with more sincerity and more depth.

Do you feel like you have been a better governor this time than when you served in the 1970s and 1980s?

Whether it is studying algebra or riding a bicycle, the more practice you have, the better you get. And I certainly have more practice being governor in my 15th year than I did in my first or my second.

The first time you were governor, you rejected living in a mansion that Nancy and Ronald Reagan had built and lived in a small apartment. This time you’re living in the mansion your father once inhabited. How does that feel?

I have to say it’s an immense pleasure. It was dead for 40 years. It was a museum. They actually had the dresses of [former first ladies like] my mother hanging upstairs in the bedrooms. And now it’s a live place. I first went there in January of 1969 and briefly visited my father, and his grandchildren would swim in the pool and now their children are coming in to visit.

You ran for president three times. Why did you want that job?

Why did I want to be governor? Why did I want to be [California] secretary of state? This is something that I find it hard to describe. All I know is I do run. I am attracted. I do everything it takes to get there … People in politics like to be in politics. They like to talk, they like to be seen, they like to hang out with people who can give them money. And then hopefully, they like, just as much and more, to do what they are elected to do. And I can say I very much like doing the work of governor of California.

In other interviews, it has seemed like you don’t want to talk about your legacy. Why?

If you actually think about it, what would that mean? Are you talking about a book someone would write about you? Even if they did, in five or 10 years, I may be dead. What good would that do? And it is kind of a morbid, backward-looking thought, whereas if you are fully alive and every day you are getting up and the sun is shining and the birds are chirping and my dog Colusa is jumping up — I mean, there is stuff to do, problems and crises. That is very exciting. But then to say, “No that can’t be what you’re interested in. There has got to be something else. That legacy thing.” I have just reflected on it and I think it is a construct with very little substantiation and very little utility in explaining anything.

Are you tired of people asking if you will run in 2020?

No. In fact very few people ask me.

Will you run in 2020?

No. [He laughs.] But I don’t mind people asking.

So will you retire to the ranch you are building with your wife in Colusa County on old Brown family land?

I don’t think I will retire, but I don’t contemplate any big electoral campaign.

Why have you decided to go to Colusa?

My grandmother used to talk about the mountain house there when I was a child, how wonderful it was and how people would stop by out there in the country, which was a day’s journey in a stage coach from the little town of Williams. There was a stagecoach stop and an inn and a post office. Now that’s all gone, the mountain house has burned down, most of the neighboring farmers have left, and yet the ranch is still there. There are three barns that are still there, and the memory is still there.

There is this idea that I had: re-inhabitation. My grandfather and his wife came from Germany and they inhabited it the first time, and now going back a second time, we’ll re-inhabit it and transform it with olive trees and a home and a micro-grid of solar energy, not connected to the electric company. And it will be a place where I can invite people and do things and learn how to live in 110-degree heat, because that is the way my great-grandfather lived, without any air conditioning. But we will have a little more comfort than that.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com