In the fall of 1986, just weeks after the release of his 22nd novel, It, author Stephen King had more than a few projects in the hopper. One, The Eyes of the Dragon, was an “Arthurian sword-and-sorcery epic” written for his daughter Naomi, who wasn’t a fan of the scary stuff. Another, Tommyknockers, was a “sci-fi epic set in the post-Chernobyl era.” A third novel, Misery, was a psychological thriller that would in a few years’ time have Kathy Bates thanking King in an Oscar speech.

Conspicuously absent: anything that qualified as an entry in the horror genre.

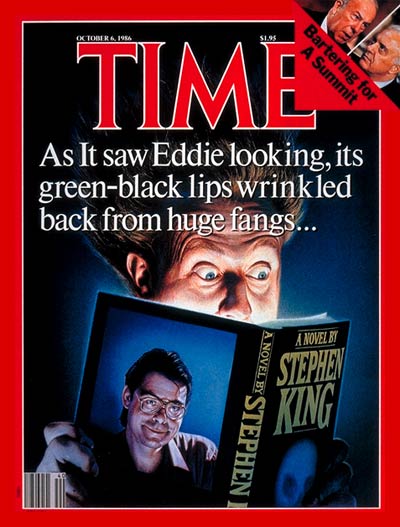

“For now, as far as the Stephen King Book-of-the-Month Club goes, this is the clearance-sale time,” he told TIME for a cover story that October. “Everything must go.” The presses still warm from printing his 1,138-page “doorstop” of a novel, as the magazine described it, the “indisputable King of horror” was ready to toss out both his bread and the butter.

Then 39, King had written nearly 20 books, with more than 60 million in distribution and a dozen adapted into movies. The pace of those adaptations would never slow and continues today — the movie It, which hits theaters Friday, is already the top pre-selling horror movie of all time. But three decades ago, he was ready to try something different.

Why? TIME’s Stefan Kanfer speculated that King’s decision might have had something to do with the competition nipping at his heels. He conceded that the British horror novelist Clive Barker was “better than I am now” and “a lot more energetic.” King was also endlessly self-deprecating in the profile, calling It, for which he had received a $3 million advance, “a very badly constructed book.” He claimed to have had no more than “three original ideas in my life” and described his writing as “the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and large fries from McDonald’s” — although given the popularity of that meal, perhaps this was less of a jab than a credit.

King’s foray into horror was, as the story explained, in part a reaction to his own laundry list of phobias, which included “spiders, elevators, closed-in places, the dark, sewers, funerals, the idea of being buried alive, cancer, heart attacks, the number 13, black cats and walking under ladders.” As a child, he was lonely, his absent father a ghost in his house. His sleep was haunted by nightmares of a local boy run over by a freight train and his gangly figure rendered him “predictably chosen last in sandlot games.” The author himself could hardly have written a better backstory.

King, of course, did not actually stop writing horror novels after It.

Of the nearly 40 books he’s written since, at least a quarter can be classified as horror, with many more horror-adjacent: suspense, psychological thrillers, murder mysteries. He’s ventured into serial drama (The Green Mile), science fiction (Under the Dome), alternate history (11/22/63) and, in his eight-volume opus The Dark Tower (begun in 1982), fantasy. His next book, Sleeping Beauties, co-written with his son Owen and due this fall, is a supernatural thriller that examines the violence of an all-male world.

As for the bounty of adaptations his stories have inspired, some have done their creator proud and others have been scarier than Pennywise the clown — and not in a good way. But King keeps enough distance not to let their quality roil him either way. In that 1986 story, he quoted the author James M. Cain, who was once asked by an interviewer if he was perturbed by having had several of his books ruined — at least in the interviewer’s estimation — by Hollywood. “No,” said Cain, pointing to his shelf. “They are all still right there.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com