Ever since the very first Women’s Equality Day was celebrated in the United States, the annual Aug. 26 event has marked more than just the anniversary of the 19th Amendment’s extension of voting rights. It has also commemorated the struggle for a deeper kind of equality in all realms of life.

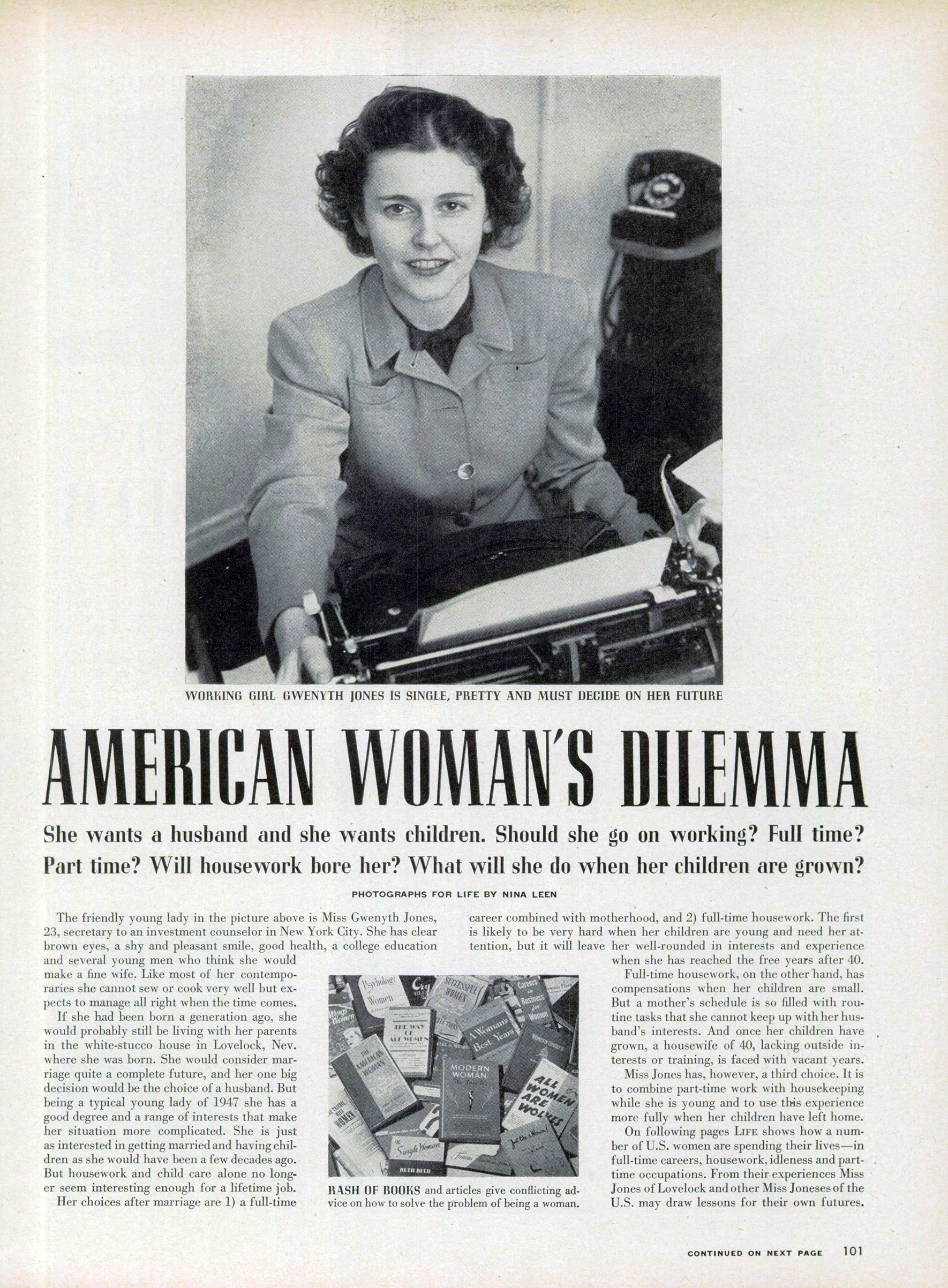

But, though much progress has been made toward that goal, some things have barely changed in decades. Case in point: LIFE magazine devoted a lengthy 1947 story to the “American woman’s dilemma,” and the details of that dilemma are problems still faced today. The sub-headline just about summed it up: “She wants a husband and she wants children. Should she go on working? Full time? Part time? Will housework bore her? What will she do when her children are grown?” These questions ring familiar to present-day debates about whether, and how, women can “have it all.”

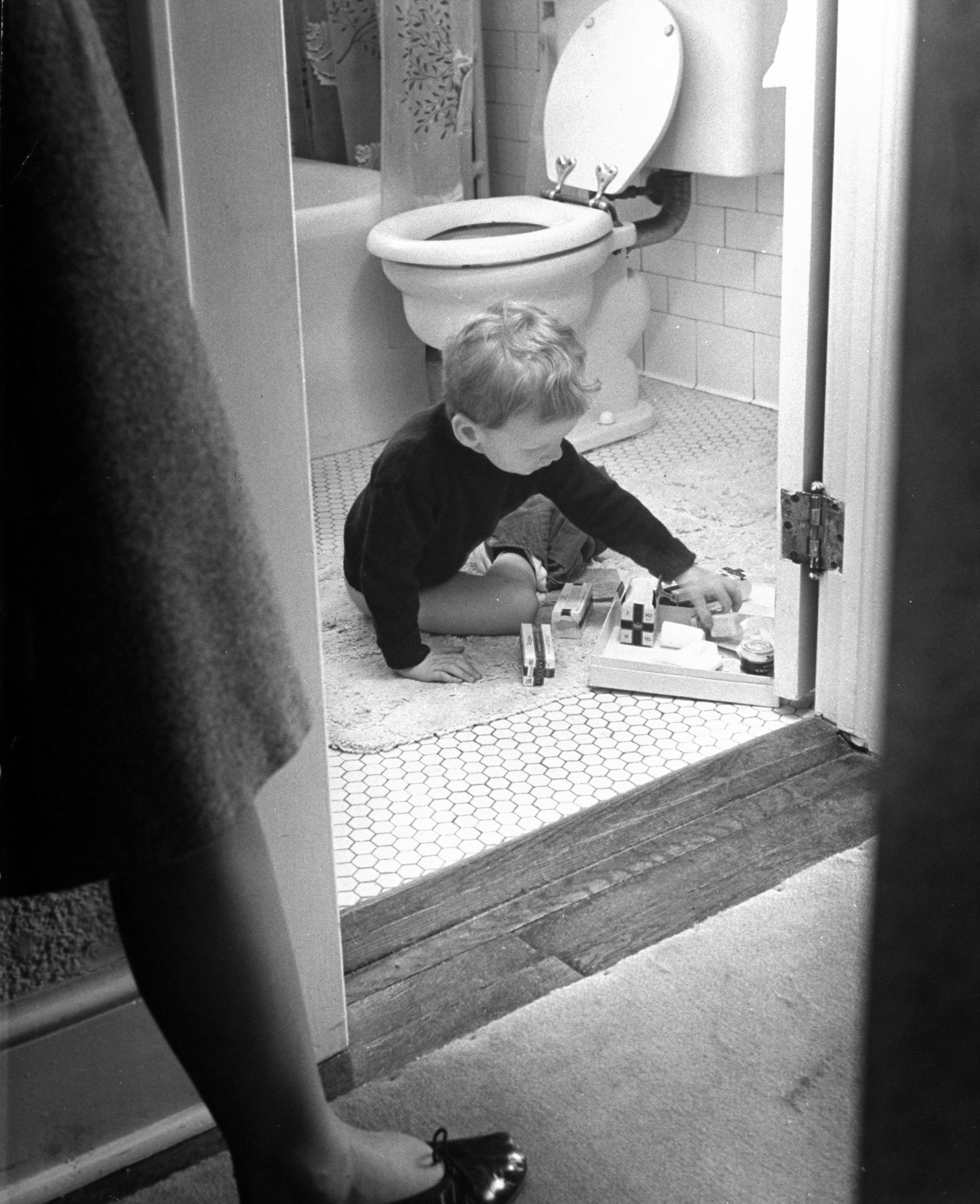

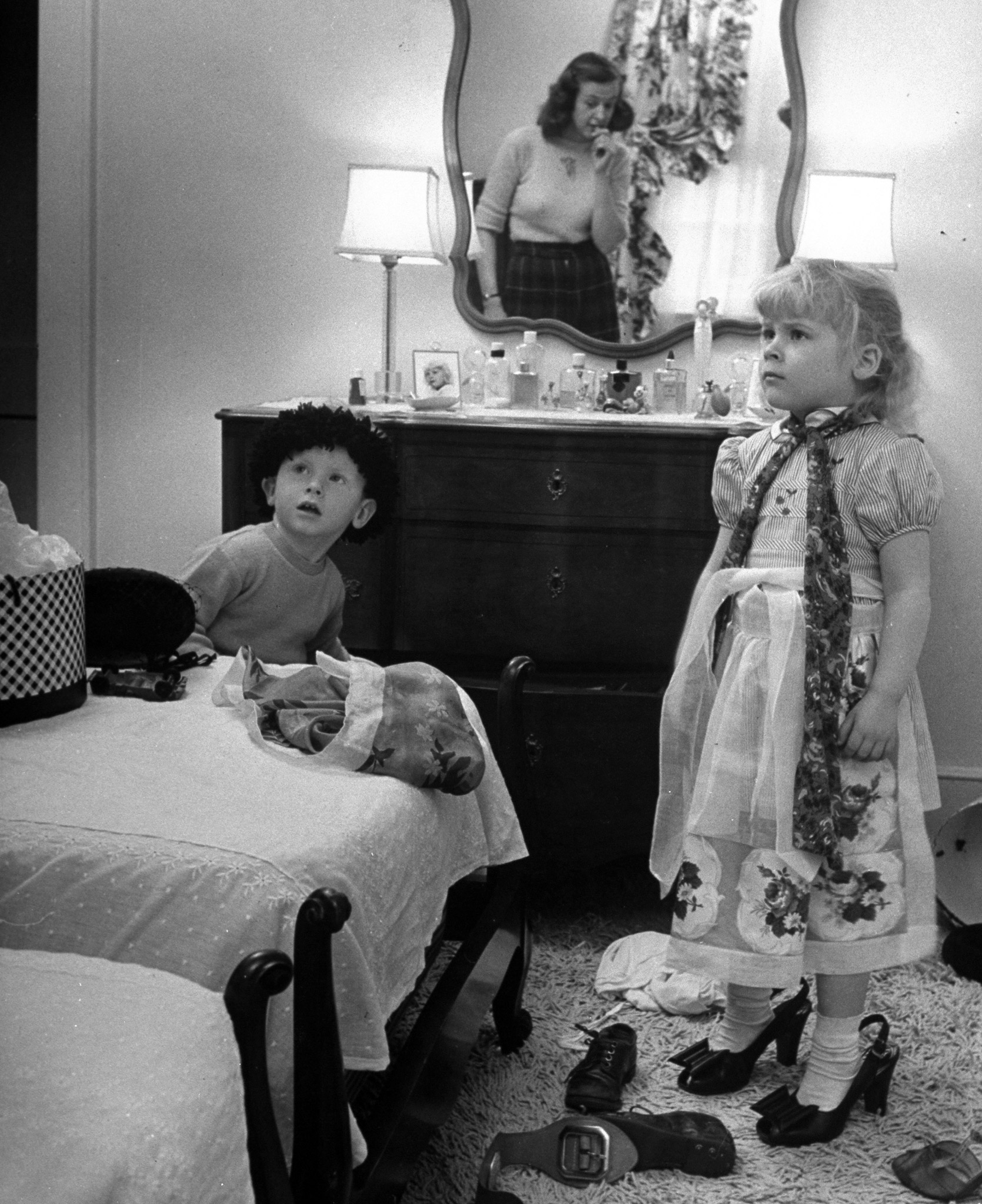

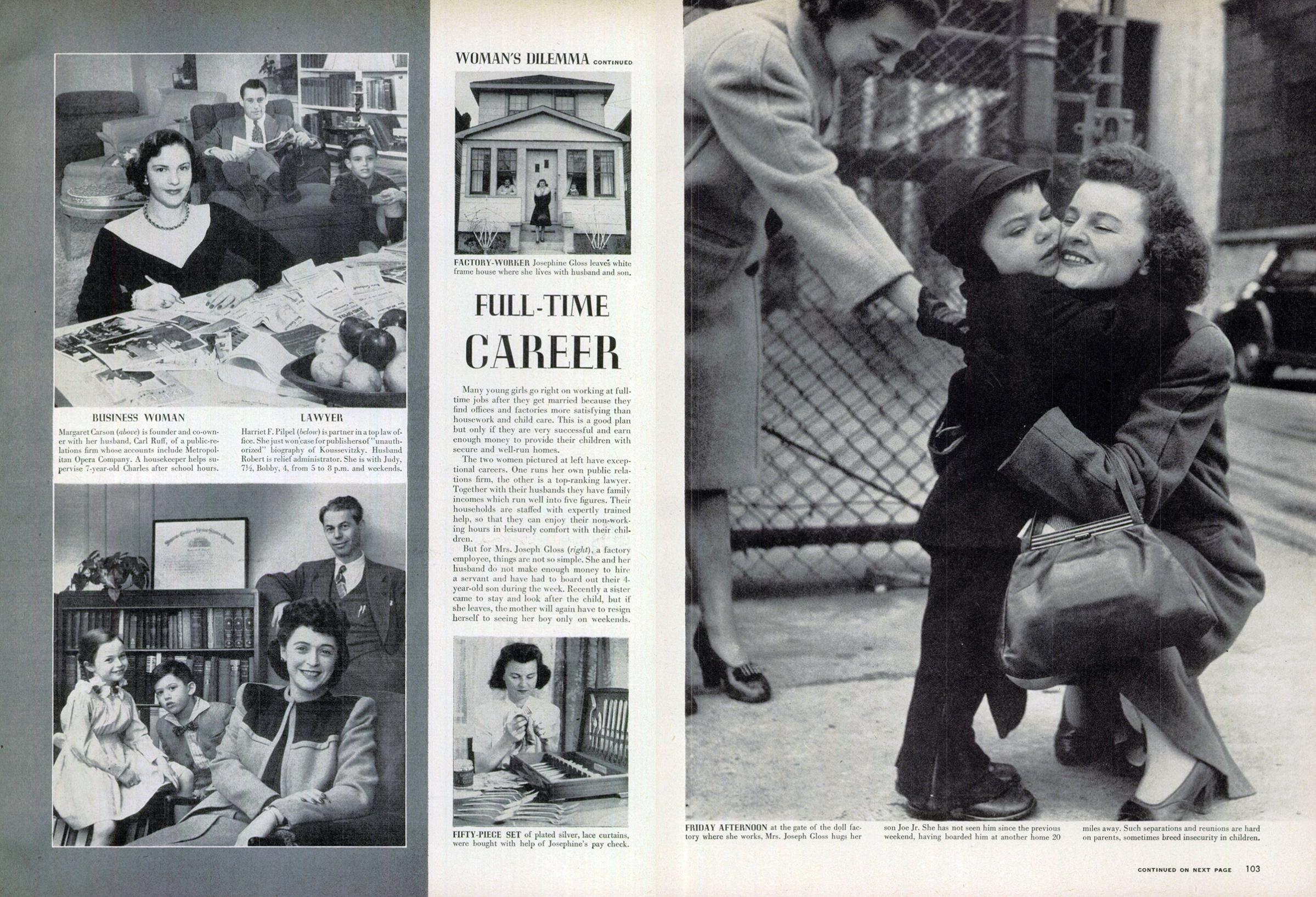

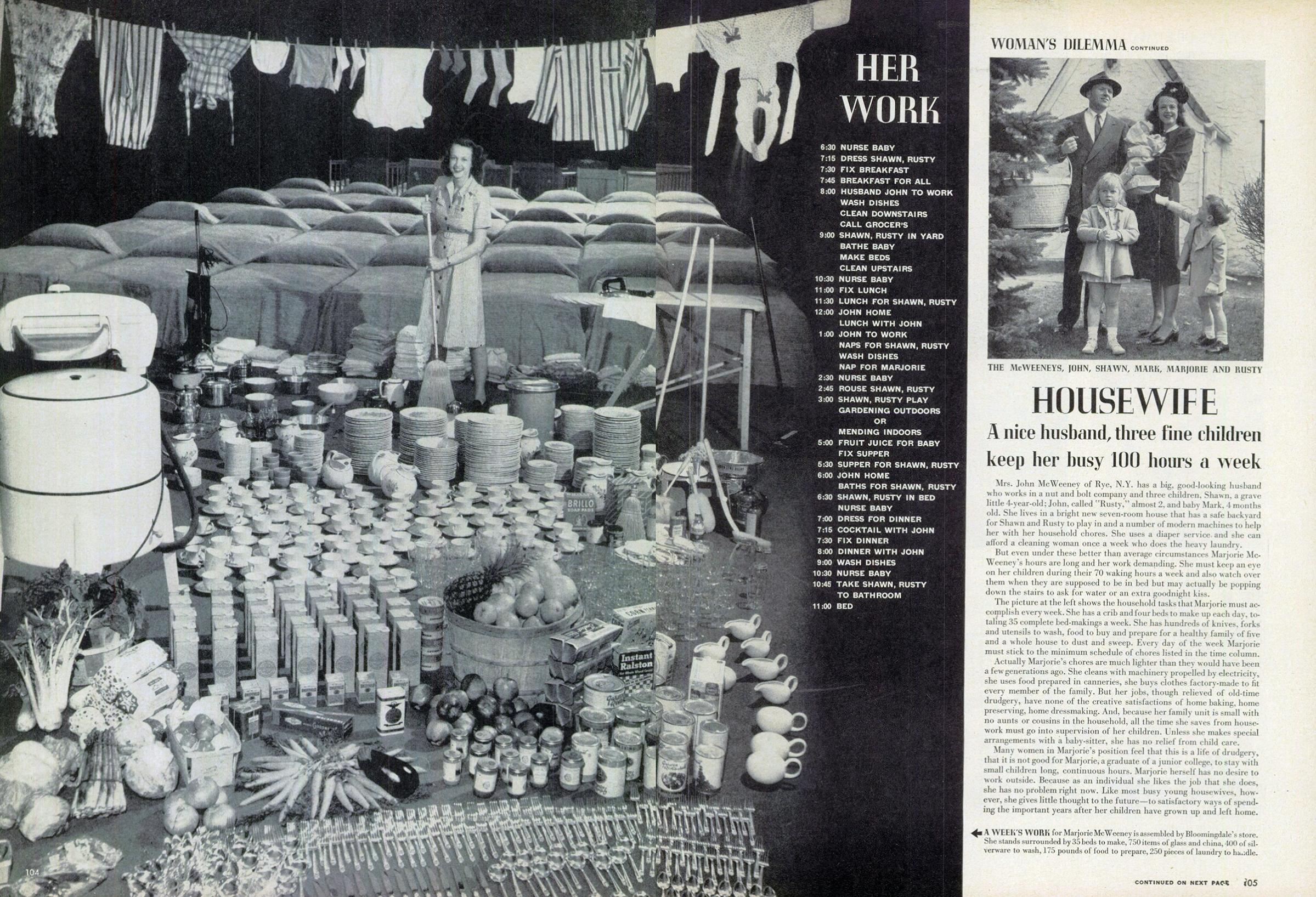

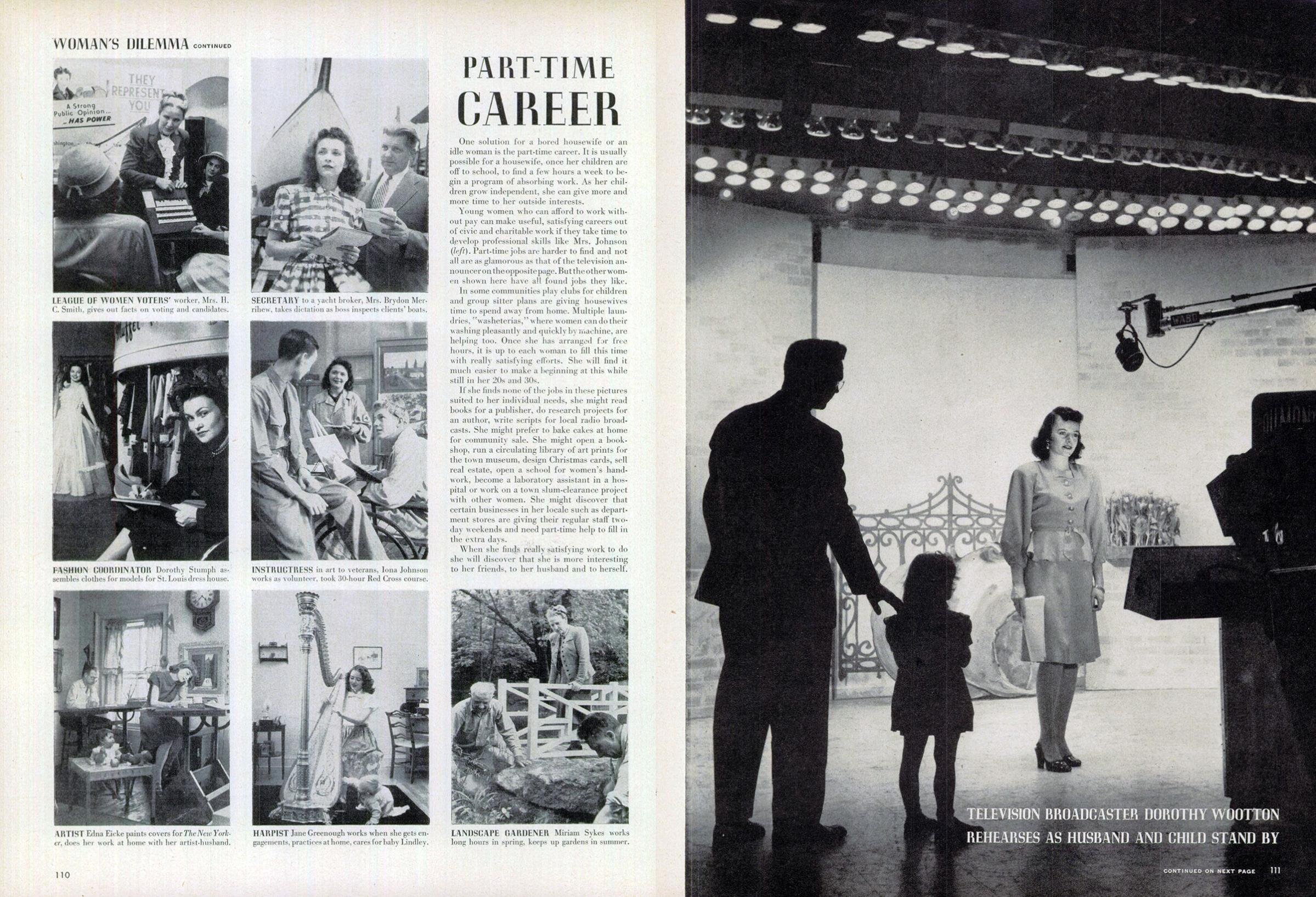

In 1947, with the post-war United States awash in considerations of how women ought best to spend their lives, LIFE profiled how a selection of American women had answered that question. A generation before, the story noted, the women in the story would likely have been happy — or at least put on happy faces — about seeing marriage as a “complete future.” But when the story was published, they could be businesswomen, lawyers, factory workers, gardeners, harpists, television announcers, secretaries or housewives, like the woman featured in the photos above — who, the story noted, did that work a whopping 100 hours a week, even with the help of modern appliances.

Many more professional avenues are available to American women today than were in the past, but the basics of this 70-year-old story will still ring true for many. The full-time workers, at least those who could afford to have a choice in the matter, had to earn enough to cover childcare costs. Those who stayed home full-time were faced with an uncertain future if they planned to return to the workforce later, though by LIFE’s count U.S. housewives at that time contributed unpaid labor worth $34 billion ($378 billion today) to the economy each year.

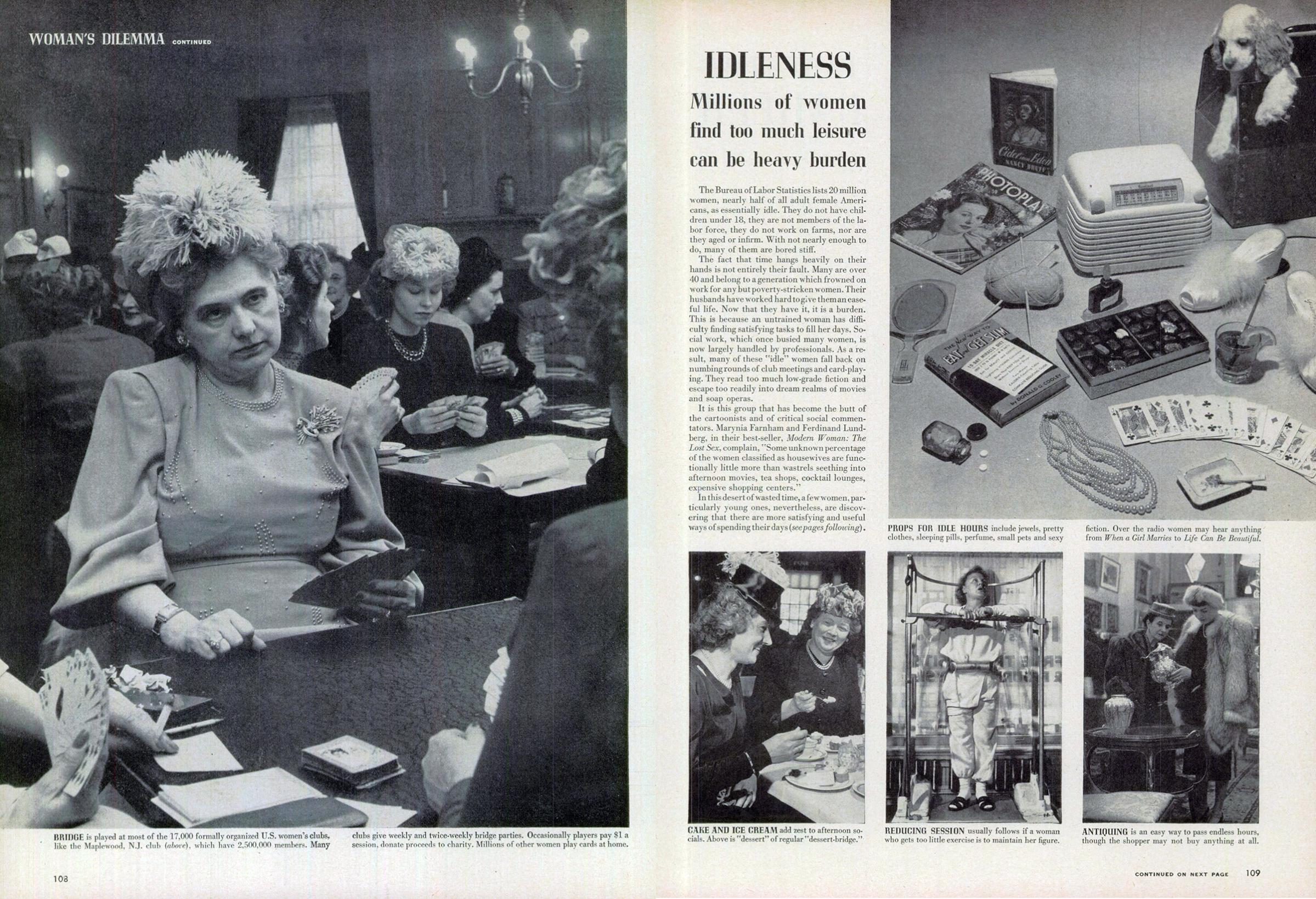

If they did not plan to return to work after their children were grown, they faced a life, in the magazine’s words, of being “bored stiff.” Part-time work was a partial solution, but it was hard to find and hardly feasible for those who actually needed the money they earned.

And, as Frances Levison wrote in an essay to accompany the story, all this analysis of the “dilemma” had an “inevitably disturbing effect” on the gender in question — serving as a reminder of one more kind of inequality faced by American women: the inequality of attention to what she was doing. “Probably no man has ever troubled to imagine,” the essay quoted the writer Dorothy Sayers observing, “how strange his life would appear to himself if it were unrelentingly assessed in terms of his maleness.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com