Reynolds, Ph.D., is Rice Family Postdoctoral Fellow in Bioethics and the Humanities at The Hastings Center.

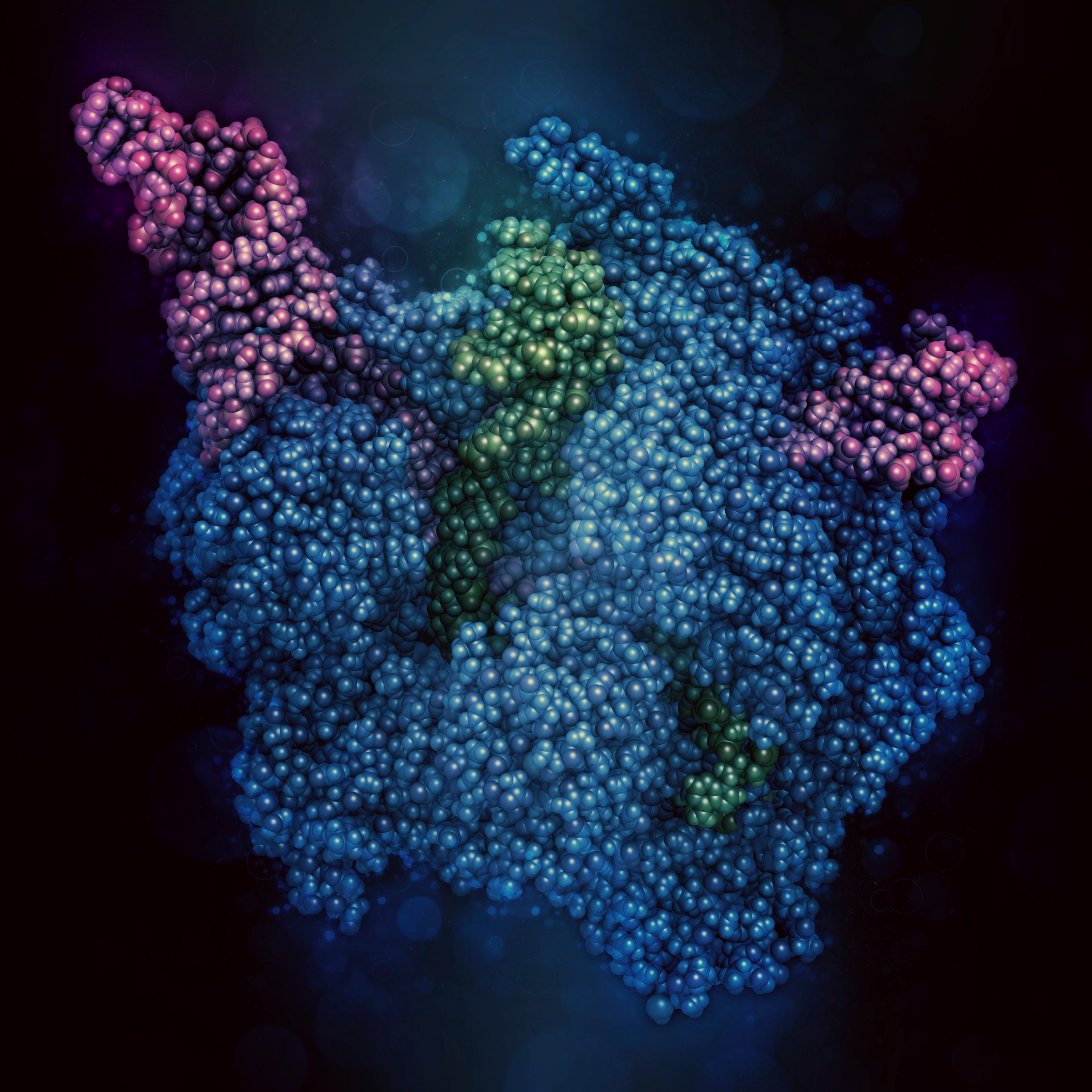

On August 2nd, scientists achieved a milestone on the path to human genetic engineering. For the first time in the United States, scientists successfully edited the genes of a human embryo. A transpacific team of researchers used CRISPR-Cas9 to correct a mutation that leads to an often devastating heart condition. Responses to this feat followed well-trodden trails. Hype over “designer babies.” Hope over new tools to cure and curb disease. Some spin, some substance and a good dose of science-speak. But for me, this breakthrough is not just about science or medicine or the future of humankind. It’s about faith and family, love and loss. Most of all, it’s about the life and memory of my brother.

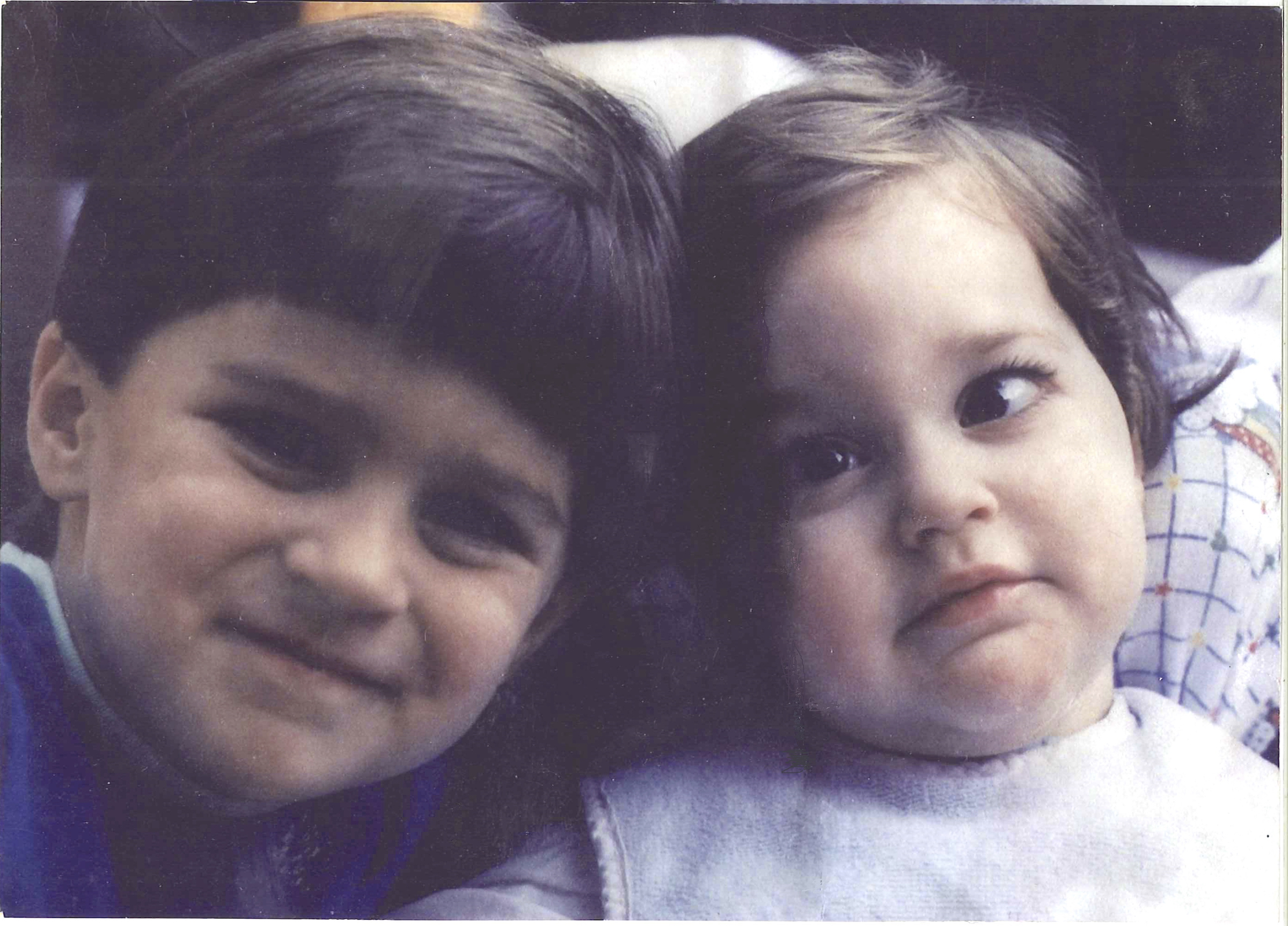

Jason was born with muscle-eye-brain disease. In his case, this included muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, severe nearsightedness, hydrocephalus and intellectual disability. He lived past his first year thanks to marvels of modern medicine. A shunt surgery to drain excess cerebrospinal fluid building up around his brain took six attempts, but the seventh succeeded. Aside from those surgeries’ complications and intermittent illnesses due to a less-than-robust immune system, Jason was healthy. Healthy and happy — very happy. His smile could light up a room. Yet, that didn’t stop people from thinking that his disability made him worse off. My family and those in our religious community prayed for Jason. Strangers regularly came up to test their fervor. Prayer “circles” frequently had his name on their lists. We wanted him to be healed. But I now wonder: What, precisely, were we praying for?

Jason’s disabilities fundamentally shaped his experience of the world. If praying for his healing meant praying for him to be “normal,” we were praying for Jason to become someone else entirely. We were praying for a paradox. If I could travel back in time, I’d walk up to young, devout Joel and ask: “How will Jason still be Jason if God flips a switch and makes him walk and talk and think like you?” The answer to that question is hard. Yes, some just prayed for his seizures to stop. Some for his continued well-being. But is that true of most? Is that what I was praying for?

The ableist conflation of disability with disease and suffering is age-old. Just peruse the history of medicine. Decades of eugenic practices. Sanctioned torture of people with intellectual disability. The mutilation of otherwise healthy bodies in the name of functional or aesthetic normality. These stories demonstrate over and over again how easily biomedical research and practice can mask atrocity with benevolence and injustice with progress. Which leads me to ask: What, precisely, are we editing for?

Although muscle-eye-brain disease does not result from a single genetic variant, researchers agree that a single gene, named POMGNT1, plays a large role. Perhaps scientists will soon find a way to correct mutations in that and related genes. Perhaps people will no longer be born with it. But that means there would never be someone like Jason. Those prayers I mentioned above? Science will have retroactively answered them. That thought brings me to tears.

I wish we could cure cancer, relieve undue pain and heal each break and bruise. But I also wish for a world with Jason and people like him in it. I want a world accessible and habitable for people — full stop — not just the people we design. I worry that in our haste to make people healthy, we are in fact making people we want. We, who say we pray for healing, but in fact pray for others to be like us. We, who say we’re for reducing disease and promoting health, but support policies and practices aimed instead at being normal. We, who are often still unable to distinguish between positive, world-creating forms of disability and negative, world-destroying forms — between Deafness, short stature or certain types of neurodiversity and chronic pain, Tay-Sachs or Alzheimer’s. It is with great responsibility that we as a society balance along the tightrope of biomedical progress. I long for us to find that balance. I’ve certainly not found it for myself. Lest I forget how often we’ve lost it and how easy it is to fall, I hold dearly onto the living memory of Jason. I no longer pray for paradoxes, but for parity — for the promise of a world engineered not for normality, but equality.

But that world will never come if we edit it away.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com